Donald Rumsfeld Was a Monster Only Washington Could Create

In a decades-long political career, Donald Rumsfeld was known for two things: covering his own ass and having few real political principles. Relentless warmongering powered his rise to the top in Washington — and led him to help orchestrate one of the worst disasters in the history of US foreign policy.

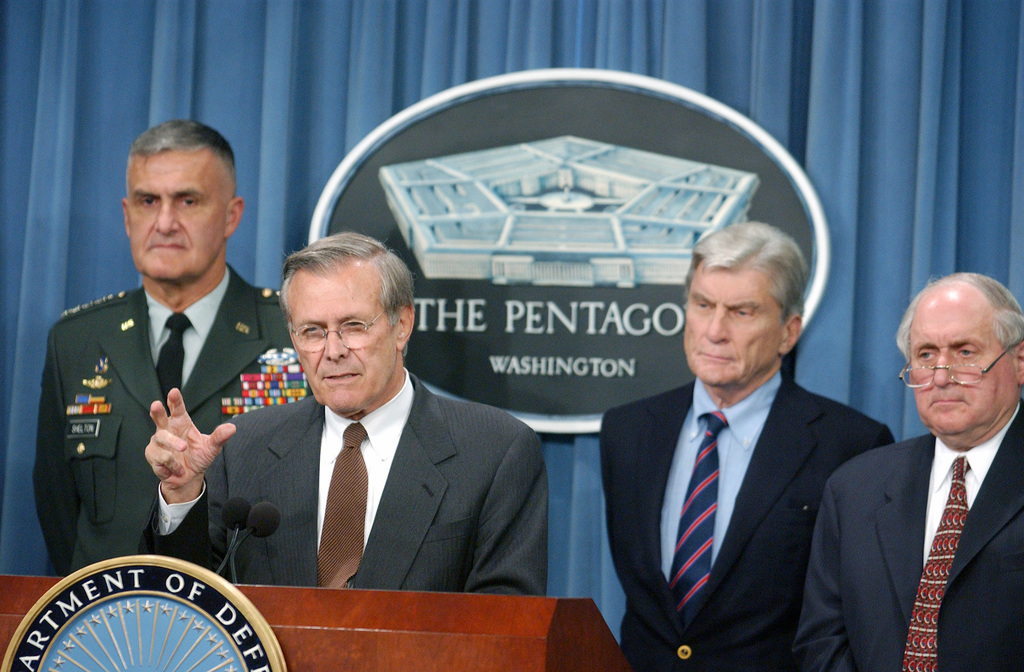

Donald Rumsfeld smiles prior to updating reporters on the progress of Operation Iraqi Freedom on Oct. 27, 2003. (US National Archives)

Donald Rumsfeld, who died peacefully on Tuesday at the age of eighty-eight, was the ultimate Washington bureaucrat. Had he been born in almost any other country, his cunning and ruthless ladder-climbing might have culminated in some scandalous kickback scheme, or the bulldozing of a poor neighborhood to make way for condos — terrible but relatively small-scale atrocities.

As it was, Rumsfeld spent his life clawing his way up the Beltway ladder, a place where quiet conversations in small rooms incinerate families and raze villages, and his career ended in the destruction of a country, the destabilization of a region, and at least hundreds of thousands dead.

Rumsfeld was everything the political establishment claimed to despise about Donald Trump. He was an inveterate liar who spent years cheerfully deceiving the US public on a near-daily basis. He was an authoritarian who was no stranger to attacking the press or flouting laws. And he profited handsomely from his place in government and the dizzying web of investments perfectly calibrated to capitalize on it.

But being a creature of the establishment — he went to the right schools, knew the right people, said the right things — he will be remembered with a degree of respect that Trump will never see.

Just a Man and His Will to Survive

Throughout his years in Washington, Rumsfeld became known for two things.

“Rummy is a survivor,” one Army general once said. “He’s very ambitious, and he’s an expert in covering his own ass,” a White House aide once put it, less politely. “First and foremost, he’s a tightrope walker who keeps his balance by playing it politically safe,” said a former underling. “He not only can walk the tightrope, but he is one of the greatest line straddlers in the business. He’s got a superb instinct for survival.”

As those words suggest, the other thing he was known for was his flexible political commitments. He was “a party pragmatist of vast ambition and no settled political philosophy,” as Pat Buchanan once described him. “He has a kind of pragmatism that doesn’t relate to any clear set of principles,” a member of Congress said of him. “I don’t think Don could list the five principles that mean the most to him. He’s a kind of mechanical, upward-mobile guy.” Another acquaintance charged that “he doesn’t think anything is important enough to spill blood for.”

These were attributes that served him well on the Capitol. Rumsfeld first entered Congress in 1963 at the tender age of thirty, representing Chicago’s affluent and largely white North Shore for three terms in the House, and quickly aligning himself with corporate interests, voting in line with the Chamber of Commerce and against the AFL-CIO.

But, true to his ambition, Rumsfeld’s conservatism fell away over the subsequent years. Boasting a 100 percent Americans for Constitutional Action score and an 80 percent support rate for the House conservative coalition in his first term, those numbers dropped to 73 and 61 percent, respectively, by his third. In 1965, he made the fateful decision to help Michigan Republican Gerald Ford in his quest to rid the GOP of the stink of Barry Goldwater and topple old-line conservative Charles Halleck as House minority leader.

Rumsfeld’s political flexibility was key to his rise. He got his first taste of government at the behest of Richard Nixon, who tapped a reluctant Rumsfeld four times to head the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), birthed years earlier out of Lyndon Johnson’s “war on poverty.” Rumsfeld was an ideal choice, given Richard Nixon’s aim to take apart Johnson’s legacy: he not only had a habit of voting against public spending and anti-poverty programs, but he had voted both against creating the office and, repeatedly, funding it.

Rumsfeld spent his tenure weathering scandal after scandal: complaints and sit-ins over alleged discriminatory practices; turning the office over to private investment for the sake of making its thrust not “in welfare or caring for people but in economic opportunity”; running afoul of union reps by reshuffling hundreds of jobs and replacing the entire civil rights division.

A loyal soldier, he tried, unsuccessfully, to devolve decision-making to regional offices, threatening to put the OEO’s anti-poverty programs at the mercy of anti-government fanatics like then–California governor Ronald Reagan, and fielding fierce opposition from lawyers’ groups. One day, at a White House prayer breakfast, he watched Nixon tell the long-serving director of the office’s federal legal services program for the poor: “You’re the guy who is causing all the problems over there.” Not long after, he fired him and his deputy, with the ex-director charging political retaliation, having sued Reagan and other conservative state officials over their actions.

Doubling as a presidential assistant, Rumsfeld cozied up enough to become one of the handful of advisers in the famously paranoid Nixon’s inner circle, eventually managing to have himself plucked from the embattled OEO post by the end of 1970 and set up as full-time counselor to Nixon. When Watergate ended Nixon’s presidency, Rumsfeld was rewarded by his former coup leader, Ford, now the incoming president, with an invitation into his more moderate White House. He seamlessly slotted in, first as chief of staff, then as secretary of defense. Years later, after Reagan took over the party and shoved it into a hard right direction, Rumsfeld didn’t miss a beat to transform again.

“The last thing we need to do is increase the tax take and the role of the federal government,” he fulminated in 1984.

“Just a Little Bit Crazy”

It was as Ford’s defense secretary that Rumsfeld may have found his true calling. As elastic as his principles were, one thing would stay consistent through the years: a commitment to the Washington war machine and an unwaveringly aggressive military posture.

At the head of the Pentagon, Rumsfeld invented stories of a Soviet military behemoth imminently outpacing the United States to argue for bigger and bigger defense budgets and more aggressive actions on the world stage. While a country “can be provocative by being belligerent,” he said, “you could also be provocative by being too weak and thereby enticing others into adventures they would otherwise avoid.”

Rumsfeld warned that space would become a new theater of battle, and he took a posture on nuclear war that can only be described as unhinged. While calling for the fantastical vision of nuclear strikes that were “deliberate and controlled,” he warned the United States needed to go further than merely wiping whole Soviet cities off the map in reply to a nuclear attack on US soil. Any retaliation, he said, needed to “retard significantly the ability of the USSR to recover from a nuclear exchange and regain the status of twentieth-century military and industrial power more rapidly than the United States.”

It’s not for nothing that New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman would later deem Rumsfeld “just a little bit crazy” — a positive thing, in his view.

Perhaps Rumsfeld’s lasting legacy in the position was to maneuver behind the scenes to torpedo a second SALT arms control pact with the Soviet Union, as Henry Kissinger would bitterly complain years later. Rumsfeld made use of shifting political conditions, Kissinger’s loss of influence, and Ford’s trust in him to concertedly undermine Kissinger’s attempt at détente with the USSR.

Ford would remain an implacable foe of arms control in the decades (mostly) out of government that followed, using whatever means he could to push the US foreign policy in a more belligerent direction, whether aligning himself with racist conspiracist neoconservatives like Frank Gaffney, or becoming an adviser to 1996 GOP presidential candidate Bob Dole. Arguably most influential was what came to be known as the “Rumsfeld Commission,” which produced a report in 1998 on the United States’ vulnerability to foreign missile attack so fearmongering that the CIA objected to it as divorced from reality.

Cashing In

Government work wasn’t just a matter of prestige for Rumsfeld. It was also a source of great profit.

From his earliest days, when he left investment banking and drew on copious corporate support to put himself in the House, Rumsfeld could be shameless about mixing his political career with his personal enrichment. After becoming president of pharmaceutical giant G.D. Searle & Co. in 1977, Rumsfeld briefly dipped back into . . . let’s call it “public service,” joining Reagan’s transition team in 1980. By that point, he had already pledged to “call in his markers” to get stalled FDA approval for aspartame, an artificial sweetener discovered by the company that had earlier been the subject of government accusations of fraudulent lab testing practices.

By sheer coincidence, Reagan’s FDA commissioner appointee quickly approved aspartame, before leaving the FDA a little more than a year later to work for Searle’s public relations agency. Aspartame is today the most widely used artificial sweetener in the world, found in more than six thousand products, from candy and cereal to condiments and “diet” sodas. This, despite serious concerns about its safety, the existence of ongoing research linking the substance to a variety of illnesses, including cancer, with the most recent such study published in April this year.

Through the 1990s, Rumsfeld sat on the board of directors of at least six companies, including Kellogg’s, Sears, Roebuck and Co., and another pharma giant, Gilead Sciences, of which he became chairman in 1997. The latter proved a particular windfall for him, with his significant shareholdings in the company — which he was advised not to sell upon entering government, lest he be accused of insider trading — netting him a $5 million capital gain during the 2005 bird flu scare.

The Crime of the Century

All of this was prelude for what would be Rumsfeld’s greatest claim to fame, when he succeeded in getting himself into the defense secretary’s office for a second time, this time under George W. Bush in 2001.

Rumsfeld had had a hostile relationship with the elder Bush and, according to Andrew Cockburn, used the younger Bush’s own testy relationship with his father to manipulate him into putting him in his cabinet. The administration would prove something of a reunion for Rumsfeld: Bush’s vice president was Dick Cheney, who Rumsfeld had installed as Ford’s chief of staff upon going to the Pentagon and served as something of a mentor to.

Like Bush’s presidency as a whole, were it not for the September 11 terrorist attacks, Rumsfeld’s time at the post might’ve been remembered as a curiosity. Rumsfeld declared war on waste in the military, and on September 10, 2001, he gave a speech labeling “the Pentagon bureaucracy” the greatest threat to the country’s national security.

A day later, everything changed. Overnight, Rumsfeld became one of the chief proselytizers for a global “war on terror,” one that would go beyond just military force to encompass every field of government, and calling for the biggest jump in defense spending since the Reagan era, while fearmongering to NATO allies to urge them to shift their mission to battling terrorism. In place of ferreting out waste and shrinking the sprawling military bureaucracy, Rumsfeld put into motion the very policy program that would escalate both to never-before-seen heights.

In the process, Rumsfeld frequently acted in authoritarian ways. He attacked the press and critics for entirely accurate prognostications about the progress of his wars, which he castigated as “misinformation” — fake news, in other words. He approved, and soon disbanded once it became public, the Office of Strategic Influence at the Pentagon, to spread propaganda and outright falsehoods through the media, and to “coerce” and “punish” journalists to otherwise report in ways favorable to US government interests.

Most outrageously, Rumsfeld personally approved the torture that would become a permanent stain on the United States. “I stand for 8-10 hours a day,” he wrote, helpfully, on the memo in question. “Why is standing limited to 4 hours?” When it was revealed to the public, he defended the torture of Guantanamo Bay detainees, whose ranks included completely innocent men scooped up by lawless US forces, as “humane,” “appropriate,” and “fully consistent with international conventions,” lying that “no detainee has been harmed” and that the prisoners were only shackled while in transit.

Rumsfeld’s “war on terror” quickly became a monument to imperial hubris. Despite not knowing what languages were even spoken in Afghanistan or who exactly he was meant to be fighting there, Rumsfeld blithely assumed the US invasion of the country would be over quickly. When that ran aground on reality, at one point, Rumsfeld suggested that the United States “ought to go after Iran — hard,” as a “diversion (or a “sensible redirection of the public’s focus,” as he would later correct by hand) from the “hair knot” in Afghanistan, and to save the United States from looking impotent. For the rest of his time in government, Rumsfeld would steadfastly mislead the public about the course of the war he knew was going poorly.

But the most egregious bit of imperial overreach Rumsfeld had a hand in was the illegal Iraq War, launched on lies, which Rumsfeld quickly became an enthusiastic salesman for, despite knowing full well that the intelligence on Saddam Hussein’s supposed weapons of mass destruction was sketchy at best.

Having, like other members of the Bush administration, already decided to take out Saddam the moment the unrelated September 11 attacks happened, Rumsfeld used public anger, his platform, and the chummy relationship he had built with the press corps to lie the American people into a ground invasion of the country. He told the public there was “solid evidence of the presence in Iraq of Al Qaeda members,” that Saddam had “amassed large, clandestine stockpiles of chemical weapons,” and that Iraq “poses a serious and mounting threat to our country,” among other lies. He also told them the war would take “six days, six weeks. I doubt six months.”

Of course, like Afghanistan, the longest war in US history, Iraq soon turned into a bloody quagmire that lasted far, far longer. As Spencer Ackerman has pointed out, we will likely never know its full death toll, owing to Rumsfeld’s own policy of deliberately not trying to count it, but by one estimate, the war killed as many as 204,575 civilians.

Its consequences went well beyond this number, however. As brutal as Saddam was, the vacuum of power left by his sudden ouster resulted in a civil war, and the explosion of sectarian conflict and violence within the country. In the long term, the war resulted directly in the rise of ISIS, fueling the very problem Rumsfeld had claimed to want to fight and destabilizing the region as a whole. And it produced an irreparable loss to human civilization in the form of an unchecked black market for Middle Eastern antiquities, with terrorists and desperate Iraqis alike turning the land into a pockmarked lunar surface, digging up long-buried objects to sell to wealthy collectors, resulting in the permanent loss of whole swaths of ancient human history.

Unlike Robert McNamara — another number-cruncher defense secretary with hands covered in unimaginable amounts of blood — he didn’t even have the bare minimum of decency to show some self-reflection or contrition for what he had done. To the very end, Rumsfeld was a self-satisfied, smirking cipher, continuing to insist that the Middle East was safe with Saddam gone, and that he had been right all along.

For some, none of this will matter. These are, after all, merely foreign lives that he took, unimportant in the grand calculus of Washington foreign policy.

But by 2018, nearly fifteen thousand Americans — troops, civilians, and contractors — had lost their lives in these two wars, too, making Rumsfeld responsible for roughly five times the number of Americans killed in the terrorist attacks that had justified the wars in the first place. These Americans dead and maimed were put in particular jeopardy by Rumsfeld’s insistence, against criticism from military strategists, on going to war with insufficient manpower and resources to fulfill his harebrained obsession with proving Saddam could be beaten with a light force.

As a final kicker, the carnage he unleashed on US soldiers was very likely one of the deciding factors that eventually put Trump in the White House. From the expansion and consolidation of authoritarian institutions, to continuing instability in the Middle East, to the blowback it all caused in the domestic sphere, we will be living with the fruits of Rumsfeld’s late-period career for a long time to come.

He’s a Survivor

There’s little doubt from surveying the ghastly wreckage of Rumsfeld’s political career that his description as “one of the greatest line straddlers in the business” was correct. But, more than prompting us to think about the wretched nature of the man himself, it should lead us to ponder the political institutions and culture that made this true.

What does it say that Rumsfeld, a craven bureaucratic ladder climber with a near-pathological aversion to holding any principles, used a militant advocacy for US military aggression as his ticket to the top rungs of power? What does it say that a man who didn’t “think anything is important enough to spill blood for” nonetheless viewed endless blood-spilling as premium currency for his career?

Rumsfeld was a monster, and a talented one at that, but replace him with another unscrupulous bureaucrat with one eye on his résumé in the world’s imperial heart, and you probably would’ve gotten a similar outcome. Congratulations to him, though. By dying peacefully at his home instead of a jail cell, Rumsfeld once again weaseled out of any accountability or consequences for his litany of misdeeds. A survivor to the end.