When Women Negotiate

Women experience backlash when they're assertive about pay — and the problem won't be solved by "Leaning In."

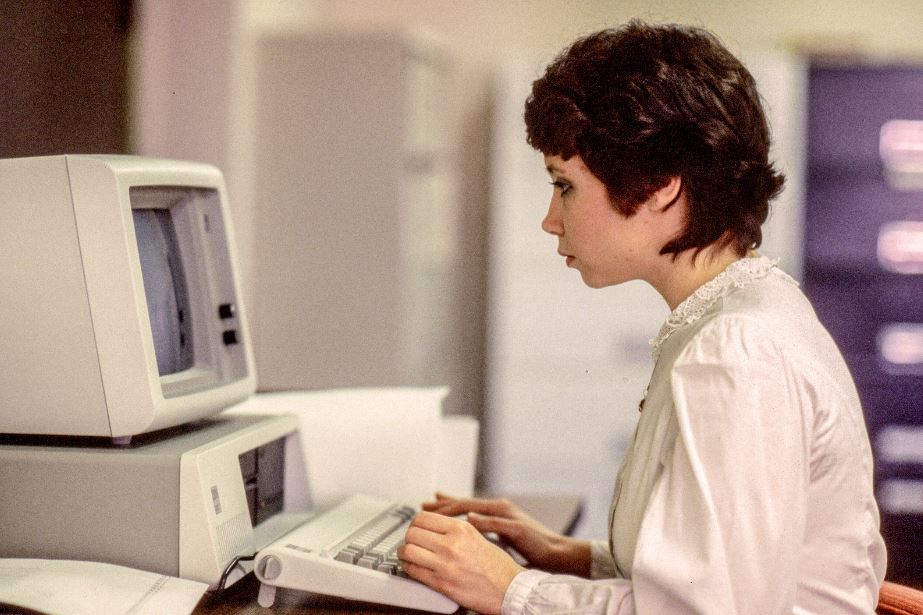

An office worker in Boston, MA in 1978. Spencer Grant / Boston Public Library

It’s something we’ve all wondered: in the middle of a stressful job-interview process, when is the right time to bring up pay?

For a Canadian woman named Taylor Byrnes, the answer, apparently, was “never.” Byrnes was interviewing for a job with a Canadian startup called SkipTheDishes. After her first interview (the second was a “menu test” which she presumably had to study for) she inquired about the salary and benefits package of the job in question. SkipTheDishes responded that “your questions reveal that your priorities are not in sync with those of SkipTheDishes. At this time we will not be following through with our meeting this Thursday.” By inquiring about pay, Byrnes had violated a company taboo and was disqualified from consideration from the job.

This story highlights perfectly the unique pressure placed on women in the world of work. We all know that there is a wage gap between men and women. We also have loads of studies telling us that women are partly to blame — they ask less, negotiate less, and demand less. Byrnes might have had all this in mind when she decided to be proactive and inquire about salary. Perhaps she even calculated the risk of being slightly bold against the payoff of making progress for all women in the workplace.

But whether these thoughts crossed Byrnes’s mind or not, SkipTheDishes’s summary rejection shows the gap between the neoliberal rhetoric of the savvy, empowered woman — who smashes through glass ceilings by sheer force of will — and the reality of working in capitalism.

There is a lie at the heart of the capitalist employment relationship: that it is a free, voluntary, and neutral relationship, between equals. This lie exists to hide the coercive essence of capitalist employment: workers enter into the relationship because they need to eat, and because without employment, they will die. Capitalists enter under no such duress; their primary goal is to produce profits.

The human needs of the worker can impede the capitalists’ ability to make that profit, so it becomes important to hide and minimize, systematically, those needs.

When workers mention their human, daily needs, instead of pretending they are simply impassioned and dedicated to creating the perfect food-delivery app, they expose the capitalist labor relationship for the coercive act that it is. This can be powerful and disruptive in the hands of a collective group, like a union. But the lone worker who dares to say out loud the real reason they seek and maintain work is taking a huge risk. Capital’s instinct is to diminish or expunge voices that set human needs against the drive for profit.

The burden to hide the real motive for working is especially heavy for women. Employers continue to harbor the suspicion that the mysterious demands of female biology will impede the demands of productive work. And they’re not totally wrong, though biology has little to do with the demands placed on women. Giving birth, raising children, cooking, taking care of elders, cleaning the home — all of this takes a lot of time, which can easily inch into the hours the employer regards as “theirs.” But while these conflicting responsibilities have historically fallen on women’s shoulders, there’s nothing inherently female about them; these are human needs, elemental for the survival and reproduction of humanity. They were just easier to hide when women themselves were hidden in the home.

The “Lean In” prescription for how women can achieve success at work simply takes capitalism’s demand that we hide our real needs and refashions it into the language of empowerment. It asks women to work twice as hard as men. It asks them to “do it all,” or at least that they insist loudly, to the people writing the checks, that they can do it all.

The Lean In approach has been roundly criticized for offering a form of women’s empowerment only attainable for wealthy corporate women. Many have rightly pointed out that women like Sheryl Sandberg can only “do it all” with the help of lower-waged women workers like nannies and cooks. Where the burden of the “second shift” could be socialized and made a public good, such as through universal child care, in our for-profit society it is privatized and hoisted onto underpaid care workers. Those who can’t afford this extra help, or provide it themselves, certainly have a harder time “leaning in” and climbing the career ladder.

But increasingly, studies show that “leaning in” doesn’t even work for relatively privileged, professional women like Taylor Byrnes. A recent Fortune headline reads “Women Ask For Raises As Much as Men Do — But Get Them Less Often.” It describes a joint study between three universities showing that women were a whopping 25 percent less likely than men to receive a hike in pay when they asked for it. Further, a Harvard Business Review article argues that “women who don’t negotiate might have good reason.” The study found that when women consistently negotiated, their wages actually decreased. “Asking for more money doesn’t always work as well for women,” the authors wrote, “In fact, women — more than men — may experience a backlash that can hurt their future career prospects.”

Taylor Byrnes wasn’t even asking for more money — she was simply asking for basic salary information. But her experience bears out the recent studies.

This isn’t to say that women should devalue themselves and defer negotiating in every situation. But no amount of individualistic self-empowerment rhetoric will overcome the drive of capitalism to resist material advances on the behalf of workers, writ large. On a global level, corporations make a lot more money when parts of its workforce are kept at deflated wages. They will not accept change without a fight.

Paradoxically, by sharing her experience, Byrnes might be catalyzing the kind of collective fight needed to counter capitalism’s investment in gendered discrimination. Her tweet about SkipTheDishes was shared over five thousand times and the resulting backlash prompted the company to issue an awkward apology and the offer of another interview. Her honesty catalyzed many other women to tell their stories of discrimination and episodes where “leaning in” wasn’t enough.

With the mood around the January women’s march and the actions on International Women’s Day, alongside the rise of socialist organizing in the United States, these conversations could germinate real labor and workplace-based action. That type of collective action has the best chance of forcing corporations to roll back sexist discrimination. But it’s important to remember that this struggle isn’t solely geared toward achieving equal pay, or making it easier for women to become managers and CEOs. It’s also vital for showing how capitalism systematically underestimates the most elemental needs of every worker.

If we recognize that “women’s work” is really humanity’s work, and that it is sacrificed at every turn for the purpose of profit, we can confront capitalism for what it really is and start to build a more just society.