Bob Crow in Rojava

Who are the British volunteers fighting with the Kurdish YPG in Rojava?

Tommy O'Riordan / Jacobin

These days, the fight against ISIS is drawing a different kind of Western volunteer. Two years ago, the media discovered that combatants from Europe and the United States were travelling to the Middle East not only to join the jihadist forces, but also to fight them.

The focus mostly fell on the Lions of Rojava, an international unit composed of veterans and former private defense contractors within the YPG, the Kurdish armed forces in Rojava. The YPG has a strong left-wing political identity, but the Lions’ profiles and rhetoric seemed to clash with the army they had joined. For example, former British serviceman Alan Duncan drew a parallel between the Kurds’ fight against ISIS in Syria and the Brits’ fight against the Irish Republican Army in Northern Ireland.

Now, the profile of the Western volunteers in the region is changing from military veterans to ideologically inspired political activists embedded in a number of organizations.

Mass Politics During Neoliberalism

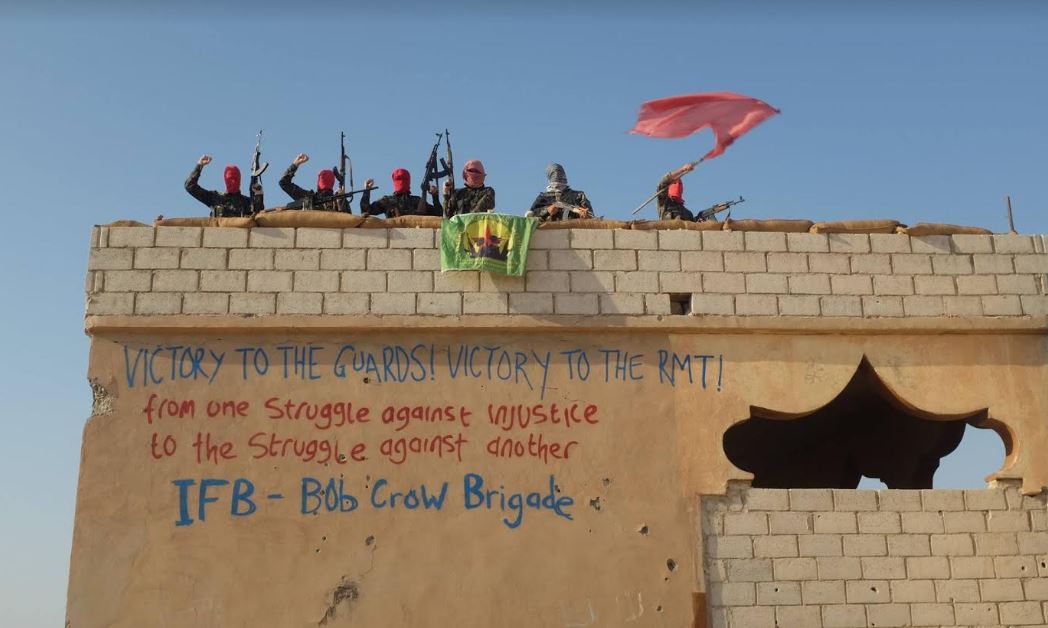

It is no coincidence that one of the units that best represents this transformation, the Bob Crowe Brigade, comes from the United Kingdom. After years of Blairism, Britain is experiencing a resurgence of left-wing politics.

The man the unit is named after may not be well-known outside the isle, but was an important, if atypical, figure in British trade unionism. During his thirteen years in charge of the Rail, Maritime, and Transport union (RMT), he raised membership from fifty thousand to over eighty thousand and launched a number of often successful struggles around wages, safety, and job security. He combined the carrot and the stick — negotiations and strikes — to ensure these victories. As former London mayor Ken Livingstone commented upon Crow’s untimely death in 2014, “The only working-class people who still have well-paid jobs in London are his members.”

These victories drew ire from the right-wing press, who attacked his salary, his council house, and his Brazilian holidays. He nevertheless publicly avowed that he took inspiration from Cuba’s success in the face of “fifty years of imperialist aggression.” He kept a bust of Lenin in his office and named his dog Castro.

Significantly enough, the bases for Crow’s political and media success were laid in the United Kingdom of first Margaret Thatcher and then Tony Blair and his Third Way. In this, he’s a different kind of figure than Bernie Sanders or Jeremy Corbyn.

Sanders and Corbyn are “survivors.” Both entered politics in the 1960s and 1970s and somehow managed to endure two decades of neoliberalism and the Left’s historical defeat before discovering their capacities for political persuasion.

Unlike Sanders and Corbyn, Crow did not just hang on during the neoliberal decades: he emerged from them. His politics were always a mass politics, and his way of talking underlined that: “If I ruled the world,” he wrote in Prospect Magazine, “I would end this idea of nations being run by a wealthy, expensively educated elite with little or no experience of the real world. Tony Blair, Nick Clegg, David Cameron? Interchangeable posh kids who think they’re doing us a favor.” Today’s liberal press would undoubtedly call him a dangerous populist.

Crow’s death most likely deprived the British left of a future leader: among the ruins of Blairism, his style would have found very fertile ground. That a unit of British volunteers has taken his name not only highlights his appeal to younger generations but also hints at the rebirth of mass radical politics in the United Kingdom.

New Internationalism

Karker Bakur, a member of the brigade, describes its philosophy:

Normal people can do incredible things if they work together, just like Bob’s life and his leadership of the RMT union showed. We have to get over this idea that we’re not qualified, not allowed to get involved in politics. Some sad cases online tried to criticize us for not being former professional soldiers when that’s our whole point — we’re normal people playing our little part in something big. Just like every trade unionist is. The better organized we are against the elite, the better this planet will be, be it on the shop floor or on the battlefield.

Indeed, the brigade regularly engages in political battles seemingly outside its purview. Over the past year, the group has periodically tweeted out its solidarity with various struggles occurring in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Last summer, for example, a surprised British press commented on the brigade’s support for the RMT strike, which was called to oppose employee reclassification at Southern Railways:

Perhaps more importantly, brigade members have established political connections between Kurdish and European activists. On September 7, 2016, they tweeted an image of two armed guerrillas wearing balaclavas and raising their left fists. Beneath them, a scrap of cardboard read: “Ni Saoirse go Saoirse na mBan [there is no freedom without the liberation of women]: repeal the Eighth.”

“The Eighth” refers to the Irish constitution’s eighth amendment, which outlaws abortion in Ireland and restricts access to information about having an abortion in England (similar restrictions also exist in Northern Ireland). The tweet must be put in the context of the international mobilization against Ireland’s anti-abortion laws, culminating in simultaneous demonstrations on September 24 in various European cities.

Karker Bakur explains the story behind the tweet:

Our women comrades in the IFB [International Freedom Battalion] asked us about the women’s movement in our countries, and we said the most heroic thing right now was the women in Ireland buying abortion pills and then turning themselves in. They were really interested in this.

After the Kurds entered the war with the Mount Sinjar Rescue, the YPJ [Women’s Protection Units] spoke to thousands of Yezidi women from ISIS who had been raped as sex slaves or as “wives” awarded to the jihadis from abroad. From that point on it became clear that ISIS’s systematic rapes were partly to leave behind future ISIS recruits, children who would be potential outcasts.

The Rojava women’s movement launched a campaign for European supporters to send abortion pills to help rescued women, and, furthermore, abortion is a completely legal process in Rojava since the revolution. So when our female comrades heard this wasn’t the case in Ireland, they asked how to show support.

Beyond these public statements, the brigade members’ biographies and self-reflections show a greater level of politicization than the Lions of Rojava. Rizgar Dêrik, a Scottish militiaman, tells us what struck him at first about the YPG:

They had a red star on their flag. That instantly made me think oh, who are these guys? I started to look into them more, started to see what they were about. I think it was around the time of Kobanê, and that just sparked my interest in the YPG and the greater Kurdish movement . . . And then from there I just decided that I wanted to take part. I could see a revolution happening, and I thought, it’s our duty to go.

As Rizgar went on to explain, political identity played an important role in his decision to join the Bob Crow Brigade. When he researched the Lions of Rojava, he realized they “didn’t necessarily have the same political views . . . or come from a similar sort of background.” He wasn’t sure “they were the right sort of organization . . . to be taking part in the revolution with.”

When I asked Rizgar about his politics, he answered without hesitation: “My dad is a communist; my grandad also was a communist . . . I was brought up being taught about the Soviet Union and . . . the Spanish Civil War.” As for his class identity, he responds: “Working class, from the British Isles. Not into using the term Britain.” When he explains what brought him to Rojava, he emphasizes two things: the lack of both employment and political opportunities back home:

Just crappy jobs, never anything permanent, random laboring in building sites and gardening here and there, bar work. Nothing with any real prospects . . .

This experience conditioned Rizgar’s political trajectory. He explains that he went to “all these various anarchist group meetings, and most of the time it was people that weren’t from working-class backgrounds, that didn’t live in working-class areas, that had no connection to the actual poor people.” As a result, “I just couldn’t really relate to [them]. Our worlds were totally different.”

He broke through this stalemate when he travelled to Rojava, where he feels “more at home than I did back in Scotland” and where he is apparently prepared to die. “I wouldn’t really say I was scared of death,” he tells us. “I mean, I’ll be doing what I can to avoid it, but if it happens, then it happens . . . For me, if I can die for something, that’s better than just sitting at home, growing old.”

Organization From Below

We shouldn’t deduce from this small sample of conversations with Bob Crow Brigade members that Europe is undergoing a process of mass politicization. For one, that would overstate the European role in this mobilization, which is being managed by non-European entities. Nor are we dealing with a phenomenon comparable to the communist mobilization for the Spanish Civil War.

In contrast to the structured party networks of the 1930s, what exists today has more to do with goodwill and revolutionary romanticism. Though social alienation and the changing political climate play an important role in triggering these fighters’ decision, the absence of a continental network capable of organizing these energies remains a substantial difference from the Spanish case.

We shouldn’t be surprised: the 1930s represented the high point of left-wing mass politics in Europe. What we are witnessing today now is, at best, a timid reawakening after decades of technocracy and neoliberal hegemony. But we shouldn’t underestimate the importance of this revival, either.

Behind Corbyn’s second victory in the Labour leadership contest and the heavy defeat suffered by Labour’s right-wing lies the same process that convinces a young Scotsman to go fight in Rojava: mass politicization. We cannot here delve into its deeper causes, but it’s clear that economic crisis, unemployment, and the consequent rediscovery of the reality of social division all play an important role. It remains to be seen where this takes us, both in Rojava and in Europe.