Pharmageddon

The Left should push rising popular outrage at drug companies' extortionate prices to its tipping point.

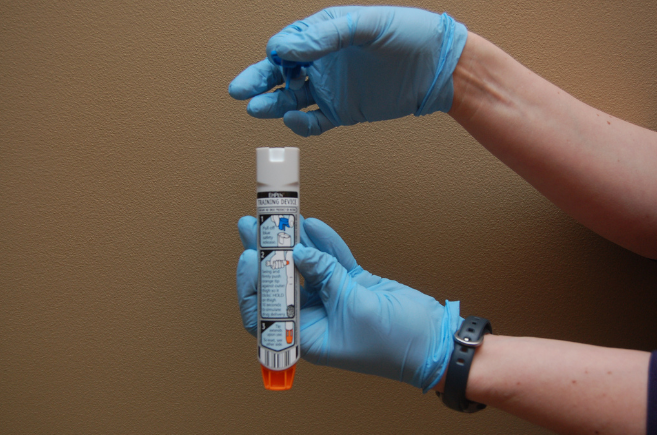

Greg Friese / Flickr

The pharmaceutical industry had a rocky start to its year.

First Senator Bernie Sanders narrowly failed to pass a budget amendment allowing for imports of lower-priced Canadian drugs. Then Donald Trump tweeted that drug companies are “getting away with murder,” and their stock prices dove. Suddenly, Big Pharma is surrounded by populists on both sides, with only a shrinking neoliberal political coalition to show for its ocean of political spending.

And it had all looked so promising. Just weeks earlier, in the shadow of the incoming cabal of billionaires, generals, and creationists that make up the Trump administration, Congress took a step it seldom risked under Obama: it passed a major bill.

The Twenty-First Century Cares Act has a number of positive provisions, including $1 billion for opioid treatment, money for the “cancer moonshot” research project, and a large funding package for the National Institutes of Health. Mainly, however, the new law lifts restrictions on pharmaceutical companies.

PhRMA, the pharmaceutical industry association, and AdvaMED, the medical device manufacturer trade group, heavily supported the bill, which significantly lowers the scientific standards the FDA uses to approve drugs and medical devices and ends disclosure requirements regarding industry payouts to doctors. The FDA will now accept shorter and less complex research studies and treat lighter levels of efficacy as adequate proof of concept. Thomas Burton of the Wall Street Journal unsurprisingly welcomed “a new, more industry-friendly era of drug and device regulation.”

As Trump, his cabinet, and the Republican-controlled Congress settle in, they will surely present the Left with a crowded field of outrages to organize around. Fighting Big Pharma should be one of our first targets. With skyrocketing drug prices, as well as with Sanders serving as the public face of resistance, today’s drug markets can become a fertile organizing field and offer convincing arguments to turn public opinion away from capitalism.

Damn the Expense

In the last year, hideous pharmaceutical price gougers have become targets of almost universal scorn. Drug giants like Valeant have openly capitalized on their patented products’ life-saving nature, cranking up prices for drugs like insulin to above $35,000 per month.

The cartoonishly loathsome Martin Shkreli took advantage of the FDA’s long and costly approval process to jack up the price of anti-parasite drugs for AIDS patients from $13 to $750 a pill. His unrelated criminal case and his close encounter with dog shit offer small solace for his top-shelf douchebaggery.

But Mylan NV reveals that drug companies rely on far more sophisticated strategies than patent laws and approval periods to drive up prices. Mainly a generic drug company, Mylan now relies on its most famous product, the EpiPen, to bring in record-breaking profits. In 2007, the company purchased the rights to produce the ready-to-use emergency epinephrine kit, whose patent has long expired.

The sticker price at the time of purchase sat at $94, but Mylan has raised the price seventeen times, to an incredible $609 for two pens. Even the American Medical Association, not known for its antagonistic relationship with the drug industry, called the prices “exorbitant.”

The conservative Wall Street Journal explains that Mylan’s “stranglehold” on the market comes from its “effective marketing and lobbying, aggressive defense of its turf, and the relatively high costs of manufacturing such sterile injections.”

Soon after buying the drug, the Journal reports, “the company effectively stoked demand for the emergency allergy treatments.” It heavily funds patient groups that promote allergic reaction awareness and preparedness in schools, airports, and stadiums. Being prepared often translates to stockpiling EpiPens.

The company has also pushed preparedness through state legislatures. The New York Times notes that “nearly every state” mandates that schools have EpiPens available, and ten states have passed laws that make “hotels, restaurants, and other places” responsible for having them on hand. Finally, new federal legislation “would require epinephrine auto-injectors on all commercial airline flights.”

When institutions like schools or stadiums buy EpiPens, they pay close to list price. The Times explains that “Mylan is well aware of that benefit” and has used medical articles written at the firm’s expense to promote these purchases.

Further, the firm is even trying to get EpiPen added to a federal list of emergency treatments, which would require insurers and the government to pay for the pens rather than patients’ co-pays, giving the company cover to “keep the EpiPen at the current price, or perhaps raise it more.”

Another trick the company tried was classifying EpiPen as a generic, which made Mylan liable for a smaller rebate to Medicare and Medicaid after the public health agencies purchased the product. This would represent an underpayment in the hundreds of millions of dollars over the 2011–15 period, and indeed, in October, Mylan agreed to pay $465 million to settle the case.

Its policy-moving prowess and grant-funded NGO smokescreen haven’t been enough to silence the outcry. Last September, the company found itself in hot water with today’s conservative Congress, and CEO Heather Bresch testified to the House oversight committee. She claimed that the company made a mere $100 on each pack of pens after costs, but the company later admitted that this was misleading:

The company substantially reduced its calculation of EpiPen profits by applying the statutory US corporate tax rate of 37.5 percent — five times Mylan’s overall tax rate last year. Without the tax-related reduction, Mylan’s profits on the EpiPen two-pack were about 60 percent higher.

Since, as the article notes, Mylan pays nothing close to that rate — in part because they recently “moved” the company to a Netherlands mailing address — this looks like a naked effort to lower the number when Bresch faces television cameras, only to quietly release a correction days later with little attention.

Mylan has launched some equally absurd public-relations efforts to smother this fire. They offered to cover co-pays for patients with certain high-deductible insurance plans, and even more ridiculously, helped launched a half-price generic version, which it also produces. The brand-name EpiPen still runs $609, and schools and hospitals will still buy it in large numbers.

Beyond the typical corporate drive for profitability, Mylan’s executives had a particular motivation behind their price spikes. The company approved a pay package worth tens of millions in additional income for its top executives if they could double the company’s per-share earnings between 2014 and 2018.

Mylan’s main business is in the lower-margin generic industry, so the EpiPen’s price point appears to have been the chosen vehicle for meeting this goal. In fact, sales of the pen accounted for 20 percent of the company’s operating profit by mid-2016. Bresch’s annual pay doubled to $18.9 million over four years, and the five highest-ranking execs raked in $300 million over five years.

A Prescription for Neoliberalism

Mylan’s case demonstrates that patent law isn’t the only way companies create drug monopolies. It also shows that competition cannot always lower prices, despite what conventional neoliberal wisdom holds.

The EpiPen once had a competitor, Auvi-Q, a similar ready-use injectable epinephrine product. Inconsistencies in the product’s dosage caused a recall in 2015, highlighting the technically demanding nature of manufacturing these drug treatments. The New York Times reports that while “many patients” would be happy to see its return, it remains uncertain if it “will do much to lower prices . . . since it [used to] cost more than the EpiPen.” In fact, when Congress grilled Bresch, she cited Auvi-Q’s price point to explain her company’s increases, since it often outpaced Mylan by 10 percent or more.

A smaller and more obscure competitor also got into the game. Jonathan Rockoff reported that “Impax Laboratories Inc. raised the price of . . . Adrenaclick to about the same level a week before Auvi-Q’s recall.” Rockoff refers to “the market’s pricing power.” But the adrenaline-shot market is a picture of modern monopoly.

Not even the Wall Street Journal can make this pro-market argument consistently. Keeping to the paper’s antiregulatory bent, columnist Greg Ip called competition “A Cure for Swelling Drug Prices,” arguing that companies would cut prices to win market share.

Ip ignores the role of patent law, delays for regulatory approval, and market-dominant positions like Mylan’s in drug prices. Instead, he depends on the gradual decrease in the cost of generic prescriptions to prove his claim, approvingly citing a study that found “within three years . . . the average generic has twelve competing suppliers and its price has fallen 94 percent.”

As often happens, the paper’s own reporting directly rebuts its editorial department. Three months later — in a perfect echo of Ip’s headline — the Journal declared that “Drugmakers Find Competition Doesn’t Keep a Lid on Prices.”

Examining Pfizer’s and Eli Lilly’s hugely popular erectile dysfunction drugs Viagra and Cialis, Rockoff reported that the companies “rais[ed] prices almost in lockstep.” He further explained:

Even when there is competition, prices can continue to climb. That is because patients tend to stick with a drug that works for them, and health insurers and drug-benefit managers sometimes have contracts for drugs that prevent switching to cheaper options.

An attractive graph illustrates the timeline of these titans’ price changes, and they resemble a pair of overlaid stairs. Since Pfizer and Lilly claim to be raising their prices independently, and absent direct evidence of conspiracy, their mirror-image pricing models are quite legal. In fact, Rockoff quotes “a former pricing official” from the gigantic Roche drug empire who admits that firms look at other companies’ increases and simply “take a similar one.”

The obvious pattern continues. Last summer, “on July 1, Pfizer raised prices by 9.4 percent, and Lilly by 9.5 percent the next day.” As Rockoff explains, “[t]he freedom to raise, rather than slash, prices in the face of competition is a big reason why US prescription-drug spending has surged by close to 10 percent on average annually in recent years to $310 billion in 2015.”

And despite Ip’s enthusiasm for generics, New York Times journalist Katie Thomas observes that while these companies “once . . . railed passionately against the anticompetitive tactics of brand-name competitors,” they are now “increasingly investing in expensive brand-name drugs and, in doing so, are embracing many of the tactics they once scorned.”

Those tactics seem to include the tandem price spikes, since several large generics firms, including Mylan, are now under two separate price-fixing investigations. Meanwhile, several state attorneys general are launching their own inquiries, spurred in part by a Government Accountability Office report that discovered almost 20 percent of generics firms “had at least one extraordinary price increase of 100 percent or more between 2010 and 2015.”

The Wall Street Journal also notes that “[s]ome labor-union health benefit funds and other drug purchasers have filed lawsuits . . . against some of the drug-makers, including Mylan and Endo, alleging that they conspired to fix the prices of digoxin and doxycycline.” The suits’ plaintiffs claim prices for the two drugs rocketed upward by 884 percent and 8,281 percent, respectively, over three years.

These legal challenges are heartening, but won’t likely lead anywhere. Price collusion cases are notoriously difficult for prosecutors to win because “[t]here must be evidence of an agreement among companies to follow each other on prices, such as a written document or telephone conversation or a meeting.” Conversations over golf at industry meetings aren’t admissible, sadly.

Cutting in the Middleman

Big Pharma is quick to defend itself, reminding critics that few consumers actually pay list price for their prescriptions. Instead, they go through insurers or pharmacies, which use their great buying power to get lower prices from the manufacturers. Of course, families without insurance or with increasingly common high-deductible insurance plans pay full price, highlighting the populist potential across the political spectrum.

Pharmacy-benefit managers [PBMs] negotiate these lower prices. They buy for big employers and health insurance companies, deciding which drugs will be covered and “using that leverage to wrest lower prices from drugmakers through rebates,” For years, “drug-makers defended” the practice, saying that these negotiations represent “a market-based alternative to government-run price negotiations” like those in the United Kingdom and Canada. Not unlike Obamacare, PBMs are supposed to make the health-care marketplace more affordable within the straightjacketed framework of small government.

Since 2011, the companies that employ PMBs have “consolidated and grown more powerful,” so that today “the industry’s top three account for three-quarters of the US market” and rake in a combined yearly profit over $10 billion.

So while hyper-profitable global firms like Lilly and Sanofi have become the target of our outrage over drug price, these very firms have begun to blame the middlemen — and not without reason.

As Denise Roland and Peter Loftus report, insulin manufacturers’ profits “have stayed the same or fallen in the past two years as the pharmaceutical companies compete to offer ever-deeper discounts to stay on the preferred drug lists at insurers and the PBM middlemen.” The difference between what an insurer pays for insulin and what the drug’s manufacturer lists the price as goes straight into the coffers of the benefit-management companies.

This fight over who gets the most of the profits earned from life-saving drugs ultimately harms patients. While drug-makers lower prices to attract PBMs, the insurance companies, pharmacy chains, and hospitals that employ them have to face spiking list prices. This has contributed to the spread of insurance and drug-benefit policies with gigantic deductibles. Co-pays, once a fixed amount, are now tied to the towering list price, and patients have to pay ruinous charges for life-saving drugs. Left activism against the Trump privatization drive and for real public services can take this issue and run with it.

Further, while PBMs aggressively secure rebates for big buyers, the largest purchaser of prescription drugs — Medicare, the public health insurance program for seniors and the disabled — cannot. That’s because the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 banned it. The legislation added prescription coverage but also mandated that the government not use its giant buying power to negotiate lower prices.

Consequently, when the public-health program released the list of drugs that cost the most in 2015, the results were pretty horrifying. For example, Valent Pharmaceuticals’ diabetes treatment Glumetza cost the agency over $150 million after the price jumped 381 percent.

“Beachhead in Cancer”

These market trends are even more pronounced in the “biotech” sector, which includes drugs designed through genetic engineering and manufactured in living cells. Here also, patent rights partially explain the gigantic prices charged for courses of treatments with these drugs.

For example, the manufacturer of arthritis drug Humira “assembled what it has said is one of the largest patent portfolios protecting a single drug — more than seventy patents over the last decade.” Even as the core patent expires, these ancillary licenses are expected to keep generic brands off the market until at least 2022.

The high cost and very challenging technological requirements for producing these drugs also keep prices high. Single courses of biotech treatments can cost tens — if not hundreds — of thousands of dollars.

Pfizer recently announced its $14 billion deal to acquire the manufacturer of the biotech prostate cancer drug Xtandi. The business press excitedly reported that the deal would give Pfizer “a beachhead in prostate cancer, complementing its breast-cancer treatment Ibrance, which is on track to be a blockbuster.”

Forget, for a second, that the only way cancer treatments can become “blockbusters” is if cancer rates also go up and just look at the numbers: globally, we spend “roughly $80 billion a year” on cancer treatment, a number that is “growing more than 10 percent annually.” The price tags on these cancer treatments “often surpass . . . $100,000 a year per patient.” The Journal lists other examples, like pharma giant Gilead’s purchase of an unapproved hepatitis C drug that it went on to price at the equivalent of $1,000 daily.

Generic biotech products, called biosimilars, aren’t likely to offer much relief. In fact, they often end up costing more than the drugs they copy. Jonathan Rockoff explains that these “paltry savings” come from the fact that patent-holding firms hike prices just before their monopoly expires “to squeeze out more revenue before competition arrives.” The generics then “set . . . their prices just below those marked-up ones.” As a result, biosimilars ultimately cost far more than the name-brand drug did before its end-of-patent price spike.

The Wall Street Journal found that “list prices for the last fourteen big-selling drugs to face generic competition rose an average 35 percent during the two years beforehand,” with the discounted price rising by an average of 22 percent.

The Left’s Opportunity

The pharmaceutical industry perfectly represents the neoliberal era, with its towering corporate power centers tightening the screws on the public with impunity. It is, however, finding itself increasingly isolated.

Last year’s giant bill kept controls at bay, but the most recent importation bill found support from both Sanders — the surprise insurgent candidate of 2016 who didn’t get his party’s nomination — and Trump — the surprise insurgent candidate who did. And crucially, an equal number of Republicans defected to vote for Sanders’s amendment as Democrats who voted against it: twelve senators of each party broke ranks.

This strongly suggests that the industry is in politically uncertain waters. But it also points to a special opportunity for the Left, with Sanders being the most nationally prominent figure confronting the industry on any consistent terms.

And while the competition isn’t lowering prices, consumer outrage seems to be. The Wall Street Journal, which usually promotes competition as a cure-all and then reports on its failures, observes quietly that “criticism of high drug prices appears to be curbing increases for expensive drugs treating certain diseases.”

It seems these corporations are afraid that rising public rancor will lead to policy action, a threat that is the real limitation to health extortion by the industry. This represents another opening for the Left—the highly unpredictable environment created by the Trump administration, and the industry’s “preexisting condition” of wide disrespect for stratospheric prices, together put the industry on the defensive, allowing a weak but lately emboldened left to tip the scales.

Capitalizing on Sanders’s association with the issue and his recognition as America’s most prominent socialist could create the political setting needed to push real progressive solutions, like importation and Medicare bargaining. And it’s an especially useful subject for forcing the Right to admit that competition is far from the magical panacea for all structural economic power that they claim.

Even other capitalists are beginning to take on Big Pharma and the PBMs. The Journal reports that “major employers including American Express Co., Macy’s Inc. and Verizon Communications Inc. formed an alliance to use their collective clout to reduce health care costs — including drug costs.”

This growing bipartisan, popular, and corporate resentment could mean drug-makers can’t muster the critical mass of senators against the next vote to allow importation or Medicare bargaining. Areas like this suggest that even in the Trump administration’s carnival-mirror landscape, real opportunities can still be found, ones that help ambivalent Trump voters see the limits of the market and the value of the public sector.

The growing populist resentment in the United States can build walls, ban refugees, and start trade wars. Or it can transform society to serve the needs of people rather than capital. The exploitative and murderous pharmaceutical sector is an ideal place in which the Left can push for the latter.