Building a Social-Democratic Majority

Why has Bernie Sanders fared so poorly with black voters? Hillary Clinton’s sweeping victories in the South on Super Tuesday — largely propelled by her overwhelming support from African Americans— have led many observers to pronounce the Sanders campaign dead.

These autopsies are premature. With nearly three-quarters of pledged delegates still in play, it is much too soon to call an end to Sanders’s primary run.

We should similarly reject fatuous over-interpretations of Tuesday’s results. The New Yorker, predictably, took the palm for class-blind condescension, suggesting that Sanders’s blowout victory in Minnesota — “Lake Wobegon territory” — revealed that his support comes from “the serene parts of the country. He has radicalized the above-average.”

Lake Wobegon may well have voted for Sanders, but the NPR donors expected to chuckle at this gibe probably did not. It is Hillary Clinton who has emerged as the favorite candidate of financially above-average Democrats. In Massachusetts she won over 59 percent of voters making over $100,000 a year; in Texas, she carried the $200,000-plus vote by 72 to 26 percent. In every state polled so far, Clinton has won a disproportionate share of support from wealthy voters.

Meanwhile, the evidence that Sanders has built a coalition based on white working-class voters — a feat unequalled by any underdog Democrat in decades — only grew stronger last week. In both Massachusetts and Oklahoma, he carried over 60 percent of whites without college degrees. Even in the South, where Clinton won big, Sanders’s strongest support came from less-educated white voters.

Nor is it true that Sanders is only winning white votes. In Texas, where he devoted very few resources, Sanders lost Latino voters by a margin of over two to one. But in the states where he has campaigned hard — and spent money — he has done much better.

When entrance polls in Nevada showed Sanders winning a majority among Hispanic voters, Clinton-friendly journalists practically tripped over themselves in a rush to cast doubt on the result. Yet all this extremely selective scrutiny produced no actual evidence that the polls were flawed beyond the margin of error.

The William C. Velasquez institute, which has been studying Latino voting behavior since 1985, conducted its own review of the data and concluded “that there is no statistical basis to question the Latino vote breakdown between Secretary Clinton and Senator Sanders.”

No Election Day polls have been taken in caucus states since Nevada, but it’s suggestive that in Colorado and Kansas, Sanders won huge majorities in heavily Latino counties. Striking local results also suggest that he has fared well with Native American voters in Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Iowa.

Overall, in four of the five non-southern states polled so far, Sanders has received the support of at least 40 percent of nonwhite voters. Calling the Sanders campaign a “white” phenomenon literally erases hundreds of thousands of these supporters.

African-American voters, however, have not yet joined the Sanders coalition in large numbers. And the magnitude of Clinton’s victory among black voters must be reckoned with. Mainstream pundits are correct that no left-wing candidate can succeed without the backing of most African Americans. So why has Sanders done so poorly?

One pundit hypothesis is that black voters have responded coolly to Sanders’s unswerving focus on economic inequality. Sanders’s “class first language,” as New Republic editor Jeet Heer put it, may have repelled black voters more concerned with racial injustice.

Hillary Clinton herself has tried to advance this explanation, arguing that Sanders’s stress on economics has made him a “single-issue candidate.” (For self-proclaimed advocates of “intersectionality,” Clinton and her allies have often seemed eager to isolate rather than connect class and racial inequities.)

A simpler theory, laid out by Philip Bump in the Washington Post, suggests that African Americans are not particularly “liberal” in the first place. Perhaps black voters have not been drawn to Sanders’s economic message for the simple reason that they disagree with it.

A look at how African Americans think about economic policy in concrete terms, however, casts doubt on this idea. According to data collected by the General Social Survey (GSS) and the American National Election Survey (ANES), black Democrats remain significantly to the left of white Democrats on most economic questions.

Over the last thirty years, black Democrats have been more likely than their white counterparts to agree strongly that “our society should do whatever is necessary to make sure that everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed.”

The barriers to “equal opportunity,” of course, are not strictly economic — and nor, some would argue, is vigorous support for “equal opportunity” an especially left-wing position. But on questions that explicitly address economic and class inequality, a similar pattern appears.

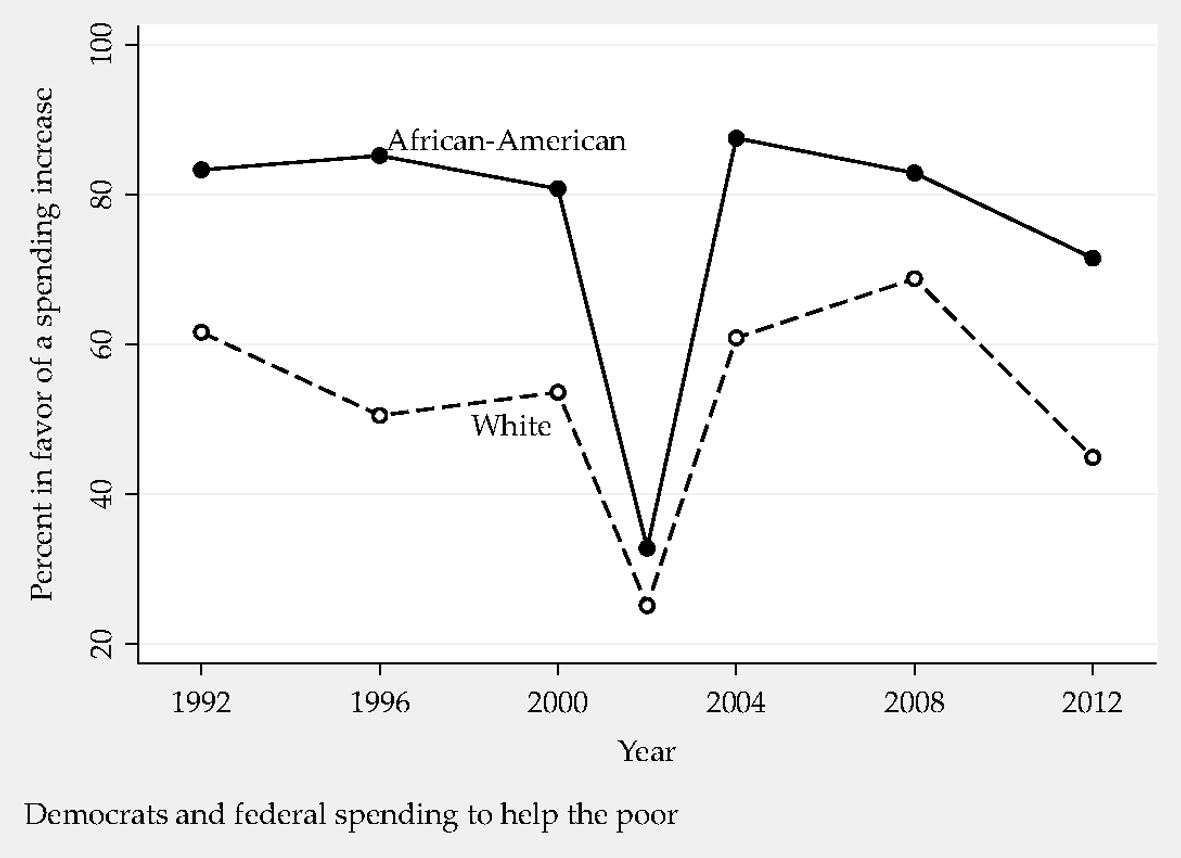

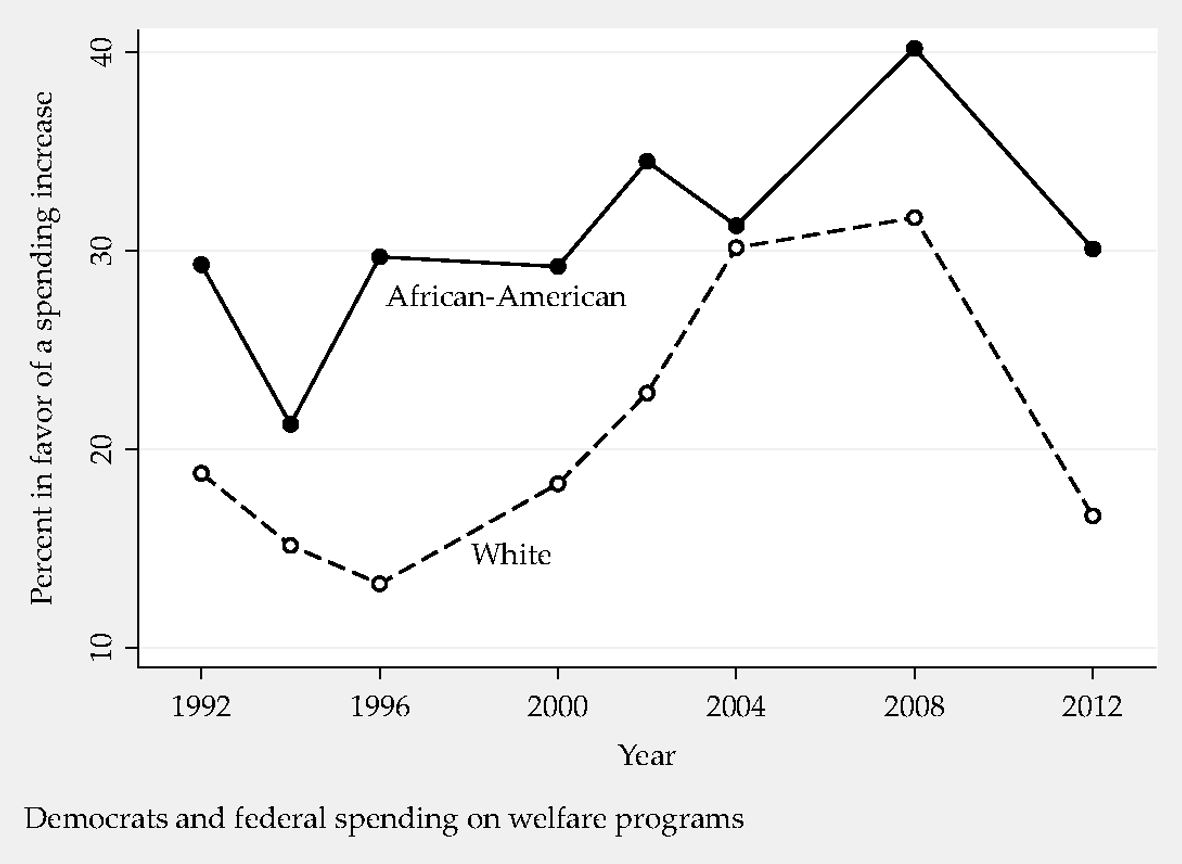

Black Democrats, for instance, are much more likely than whites to support increased federal spending on the poor.

Black Democrats have also expressed overwhelming support for financial aid to college students from poor families.

Of course, African-American views on economic policy, like any other issue, are not monolithic. But contemporary opinions seem to match the ideological spectrum described by political scientist Michael C. Dawson in 2002: “Some Blacks look like Mondale Democrats, some of them look like Clinton Democrats, and some of them look like Swedish Social Democrats — more of them look like that.”

The strength of these social-democratic leanings among African Americans shows up in recent surveys. On economic inequality, Bernie Sanders’s signature issue, over a third of black Democrats agree strongly that the government should reduce the gap between rich and poor. The proportion of white Democrats who hold the same strong view is and has been consistently much lower.

The same pattern holds on the question of welfare. While most Democrats of both races — Clinton and Mondale types — are either hostile or neutral toward welfare spending, a significant number of African Americans support a more generous welfare policy. Many fewer white Democrats agree.

Despite the growing number of self-described white “liberals,” it is hard to find any economic issue where white Democrats actually stand to the left of their black counterparts.

On the question of health care — where the racial gap seems smallest — African Americans are still slightly more likely than white Democrats to be very strong supporters of a “government insurance plan.”

(Overall, the GSS found just over 50 percent of both white and black Democrats inclined to support a public single-payer scheme.)

Two conclusions seem inescapable. One, black Democrats remain “more liberal” than whites on economic issues. Two, the economic left wing of the black electorate remains larger and stronger than the economic left wing of the white electorate.

This isn’t to say that African-American politics is inevitably disposed toward leftism. As Eddie Glaude argues in his new book Democracy in Black, black liberal elites have worked to narrow the boundaries of the politically possible since the 1970s. “Black faces in high places” within the Democratic Party, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor points out, have often played a key role in muffling or subduing grassroots struggles.

Yet if black elected officials have become more conservative over the past several decades, it’s not at all clear that black voters have followed them.

What does this mean for the Sanders campaign? If Sanders and black voters agree on so many economic issues, why has he struggled to win their support?

The ANES and GSS results suggest that Sanders’s problem has little to do with the class politics in his platform. As Seth Ackerman has argued, Sanders’s central concerns are not “white” issues.

A deeper look at the survey data reinforces other, more compelling explanations for why black voters turned out for Hillary Clinton. Carl Beijer points to Sanders’s struggle to gain media exposure and name recognition; Glen Ford stresses the pragmatic fear of racist Republicans; Cedric Johnson emphasizes Clinton’s “well-positioned black local surrogates and brokers;” and Jason Lee sharply critiques Sanders’s effort to woo black voters with “symbolic stunts” and celebrity endorsements.

Sanders’s long record as an opponent of structural racism, and his aggressive racial justice program to end racial violence, should figure among his strengths. (On both counts, as Michelle Alexander has argued, he beats Hillary Clinton by a mile.) But it may be that the candidate and the campaign have not connected racial and class oppressions as effectively as his opponents have worked to separate them.

One shred of hope for Sanders may lie in geography. It’s possible that a greater share of Dawson’s black “Swedish Social Democrats” live outside the South. In Nevada and in Oklahoma, Sanders won over 22 and 27 percent of black voters, respectively. That’s nothing to write home about, but it’s much better than his showing in the southern states, where he managed between 6 percent (Alabama) and 16 percent (Virginia).

Certainly, to remain a serious primary contender, Sanders will need to win at least 25 percent of African-American votes in states like Michigan, Illinois, and Ohio. To gain the nomination, he’ll probably need a lot more than that.

Still, Clinton’s strength with black voters may remain overwhelming even outside the South. Her advantages in every area but policy — recognition and familiarity; personal trust and party loyalty; support from local elected officials — could be too large for Sanders’s underdog campaign to overcome.

But if we step back from the 2016 horse race, a different picture emerges. “The biggest lesson of the Sanders campaign,” New York Times data analyst Nate Cohn writes, “is that there is no progressive/left majority in the Democratic Party without black voters.”

This is surely true. But from a left-wing perspective, it doesn’t sound like such a bad problem to have. What does it mean for the centrist elites at the helm of the Democratic National Committee if their electoral “firewall” in 2016 also happens to be one of the strongest bases for social-democratic politics in the United States?

Black people have been at the core of nearly every redistributive struggle in American history, from slave emancipation during the Civil War — the largest wealth transfer in the country’s history — to the Civil Rights Movement, where “Jobs and Freedom” alike inspired Martin Luther King’s March on Washington.

The conditions in 2016 may not be ripe to produce an alliance of all the progressive forces within the Democratic Party, uniting “Swedish Social Democrats” of every race into a single victorious coalition. But the dramatic and unexpected success of the Sanders campaign has made the prospect of such a realignment not only conceivable but achievable — perhaps sooner than anyone dreamed a year ago.

Most radicals, of course, are either profoundly skeptical or programmatically hostile toward the notion that the Democratic Party can ever be a vehicle for left-wing politics. They have history on their side. But advocates for realignment may have demographics on theirs.

A future candidate running on a Sanders-style platform, with strong appeal to working-class white, black, and Latino voters, would be virtually unbeatable in a Democratic primary.

Demographics are not destiny. DNC leaders, allied business interests, and the corporate media would do everything possible to resist a left-wing realignment. It would be foolish to underrate their collective power over the party, which the 2016 campaign has only affirmed.

And of course, even the election of a mildly social democratic president would only represent the beginning, not the end, of a much longer political struggle.

But suddenly, it no longer seems absurd to imagine the electoral coalition that could make this happen. Given Sanders’s cross-racial appeal among young people — in Texas, with a majority nonwhite electorate, he won 59 percent of voters under thirty, compared to just 12 percent of those over sixty-five — it’s a coalition that has room to grow.

One thing is certain: any such coalition, inside or outside the Democratic Party, must involve large numbers of African Americans.

Building this kind of alliance will not be easy. The left-wing organizers and politicians that follow Sanders have much work to do to win the attention, trust, and commitment of black voters. But they don’t need to dial back their economic platforms.