A Bernie Upset?

Can Bernie Sanders win the delegate battle? It won’t be easy — but here’s one way it could happen.

How much difference did Bernie Sanders’s historic upset in Michigan make?

At FiveThirtyEight — whose proprietary “polls-plus” model gave Sanders less than a 1 percent chance to win in Michigan — Harry Enten notes that the almighty “delegate math” still points strongly in Clinton’s favor. In the New York Times — whose even-more-secretive demographic model apparently showed Sanders losing Michigan by twelve points — Nate Cohn argues that the “probabilities” of Sanders actually winning the nomination are unchanged by the Michigan upset.

Oddly, Cohn’s crowning piece of evidence seems to be the fact that the PredictWise electoral market barely budged after Sanders’s win, giving him a 7 percent chance to win the nomination, as opposed to 5 percent the day before. Of course, this is the same online odds aggregator that gave Sanders a 9 percent chance to win Michigan on Election Day — literally nine times more accurate than FiveThirtyEight, but hardly a beacon of insight into the Democratic race.

What actually happened in Michigan? As Corey Robin says, politics happened:

that is, the contingent, unanticipated, thoroughly novel and surprising transformations that ambitious political actors — from candidates for high office of state through on-the-ground local activists and organizers — help make happen. Pollsters and pundits assume that past is future. Political beings act on the assumption that it’s not.

If Michigan should teach us anything, it is that this year’s primary campaign — like all modern politics — is dynamic, not static; fluid, not fixed. “Everlasting uncertainty and agitation,” a guy once said, “distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones.” In 2016, certainly, much that seemed solid has melted into air, from the iron rule of the GOP donor class to the predictive power of pundits named Nate.

In this spirit, I thought I’d dig a little deeper into the question of delegates. Not because it’s the defining issue of the Sanders campaign — it isn’t! — but because, well, “everlasting uncertainty” is kind of fun.

The assumptions that underpinned yesterday’s polls and today’s “delegate math” can easily turn out to be tomorrow’s breakfast of humble pie. So what follows below isn’t a prediction or even a “projection.” Over two-thirds of the delegates on the Democratic side are still for grabs — anything can still happen.

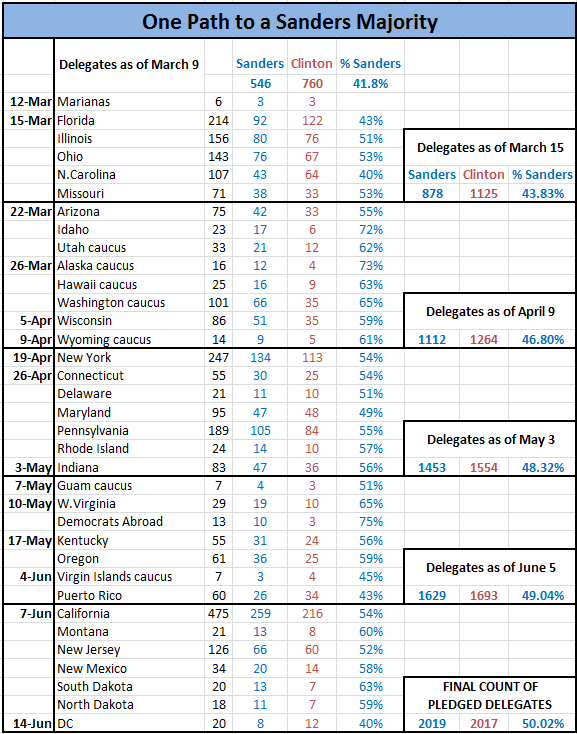

But here’s just one way Bernie Sanders could win enough delegates to surpass Hillary Clinton.

Pundits are right that to get a majority of delegates, Sanders is going to have to start recording big wins sooner rather than later. But he doesn’t need to win every state by twenty percentage points. In the scenario above, Bernie manages close wins in Ohio, Illinois, and Missouri, while staying above the 40 percent threshold in Florida and North Carolina.

He then racks up big, Obama-style victories in the western caucuses, building momentum for the April primaries on the East Coast. Medium-sized wins in New York and Pennsylvania don’t erase Clinton’s lead overnight, but they continue to narrow it. A final surge in California, New Jersey, and the western states on June 7 pushes Sanders over the top.

How plausible is this scenario? From where we stand today, it might seem like a long-shot fantasy. But so was Sanders’s hope to win Michigan, as recently as a few days ago.

There are two key elements to this Sanders victory path: one, maintaining and slightly improving his Michigan results across the Midwest and Northeast; and two, running up the score in favorable western states, including a solid win in California.

Greater Michigan

According to Michigan exit polls, Sanders’s share of the electorate looked like this: about 58 percent of white non-college graduates, 56 percent of college whites, 29 percent of African Americans, and 50 percent of non-white, non-black voters. (These percentages are based on Bernie’s share of the head-to-head vote with Clinton, leaving out the small number of “uncommitted” voters.)

These levels of support make Sanders a serious contender in every Northeastern and Midwest state: on their own, they would likely be enough to win Ohio, Missouri, New York, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Indiana.

Is it crazy to think that Sanders can keep up these Michigan numbers? In New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Oklahoma, the only other non-Southern primaries so far, Bernie’s exit polls are largely similar. (In New Hampshire, he won 69 percent of non-college whites, 58 percent of college whites, and 50 percent of non-whites; in Massachusetts, the numbers were 60 percent, 47 percent, and 41 percent; in Oklahoma, 69 percent, 54 percent, and 41 percent).

Michigan, in other words, only looks strange compared to Southern states where Sanders devoted very few resources. Across the rest of the North, it could be a bellwether, not an outlier.

Polls in Ohio and elsewhere haven’t yet showed this breadth of support for Sanders. But they never showed it in Michigan, either — and they seriously underestimated Sanders’s support in the other primaries, too (by about 6 percent in New Hampshire, 5 percent in Massachusetts, and 10 percent in Oklahoma). In some ways, your view of the race going forward depends on whether you’re more inclined to believe pollsters or Sanders’s own previous vote totals.

Simply maintaining Michigan levels of support would make Sanders a formidable competitor across the Northeast, but might not be enough win the nomination: he’d still lose Illinois and New Jersey, and his margins in the others states wouldn’t bring in the delegates he needs to surpass Clinton.

Expanding the Sanders coalition beyond his Michigan vote share will be tough — especially in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, where the large number of white college graduates may vote more like their counterparts in Massachusetts (47 percent for Bernie) than in Michigan (57 percent). But it’s not impossible.

After Super Tuesday, many commentators assumed that Sanders had no chance to crack Hillary’s so-called “firewall” of black voters. After winning no more than 16 percent support from African Americans in the South, Sanders seems to have won 29 percent in Michigan, including (according to one CNN report) 49 percent support from black voters under forty.

The Michigan result could be a quirk, but it could also be a sign that Sanders is expanding his coalition. And why should we assume that his ceiling is 29 percent? Remember what that guy said about fixed, fast-frozen relations. The “black vote” isn’t monolithic, and it isn’t set in stone. If Bernie can win even 40 percent support from African Americans in the Midwest and Northeast, he has a real chance to corral the kind of “Greater Michigan” coalition necessary to win the nomination. If he can win 50 percent, he’ll coast to victory.

Wild, Wild West

To catch Hillary Clinton, Sanders doesn’t need to win by big margins in every state. But he probably does need some yuge western routs.

The precedent for a western caucus blowout run is obvious: Barack Obama in 2008. Obama won over 65 percent of the delegates at stake in Washington, and over 75 percent in Idaho, Alaska, and Hawaii. Sanders might not quite match those extreme margins, but he could certainly approach them. In Colorado, Minnesota, Kansas, and Maine, Sanders has already managed delegate hauls that compare respectably to Obama’s totals in 2008. It’s hard to see why he couldn’t do it again in Washington, Utah, Wyoming, etc.

Appalachia, where Obama was wiped out by Clinton in 2008, should be another strength for Sanders. He needs to match (or exceed) the polls showing him way ahead in West Virginia, and win by the same margins in Kentucky, too.

If Bernie can build a “Greater Michigan” coalition in the Northeast, and win big in the West and Appalachia, it’s possible to imagine that the June 7 primaries will decide the election. Under the scenario above, he’ll need a solid win in California — over 54 percent — to surpass Clinton in the overall delegate count.

Can Sanders manage 54 percent in California? Much of course depends on his support from Latino voters, who will likely make up at least a third of the state’s primary electorate.

Here’s how I described Sanders’s performance with Latino voters earlier this week:

In Texas, where he devoted very few resources, Sanders lost Latino voters by a margin of over two to one. But in the states where he has campaigned hard — and spent money — he has done much better.

When entrance polls in Nevada showed Sanders winning a majority among Hispanic voters, Clinton-friendly journalists practically tripped over themselves in a rush to cast doubt on the result. Yet all this extremely selective scrutiny produced no actual evidence that the polls were flawed beyond the margin of error. The William C. Velasquez institute, which has been studying Latino voting behavior since 1985, conducted its own review of the data and concluded “that there is no statistical basis to question the Latino vote breakdown between Secretary Clinton and Senator Sanders.”

No Election Day polls have been taken in caucus states since Nevada, but it’s suggestive that in Colorado and Kansas, Sanders won huge majorities in heavily Latino counties.

In surveys taken over the last two months, Reuters shows Sanders running even with Clinton among Hispanic Democrats. Based on these polls and his past results, it’s not a huge leap to imagine Sanders winning 50 percent of Latino votes in California (and in Arizona and New Mexico, too).

We have even less data about Asian-American voters, who will likely make up over 12 percent of the California primary electorate. But again, Reuters shows Sanders running within just four points of Clinton among Asian-American Democrats.

To hit the 54 percent threshold in California, Sanders will need to hold onto his Michigan margins among white and black voters, plus win a slight majority — about 55 percent — of Latino and Asian Democrats.

Is this likely? Maybe not. But is it crazy? I don’t think so.

Of course, even if the race ends on June 14 in a virtual tie — with Sanders owning something like 50.02 percent of the delegates — Clinton’s enormous support from party elites (those “superdelegates”) will probably give her the nomination. But that’s an entirely different kind of “delegate math.”