Syriza’s Red Lines

On Friday, Greece delayed its debt payment to the International Monetary Fund. Is a default imminent?

A. Konstantinidis / Reuters

In the early hours of Friday morning, according to the British paper the Daily Telegraph, five key players in the Syriza government, meeting in the Maximus Mansion in Athens, made an important decision. They decided that the government would not pay the International Monetary Fund (IMF) its debt repayment installment due that day. Apparently, IMF chief Christine Lagarde was caught badly off guard. IMF officials in Washington were stunned.

The Syriza leaders had the money to pay: it had been raked up from various sources, and they had told Lagarde that they would pay. But at the late hour, they decided not to pay but instead “bundle” all the repayments scheduled for June into one payment at the end of June — or €1.6 billion. This was allowable under IMF rules but had only happened once before (Zambia in the 1980s).

The reason that Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis, and the other Greek government leaders decided to hold back payment was two-fold.

First, they were really angry that the IMF and the Eurogroup had completely refused to make any serious compromises on the terms of an agreement to release outstanding funds under the existing “bailout” package, despite the Greeks making huge concessions in the negotiations since an extension was agreed to in February.

Also, the leaders knew that their Syriza party members and members of parliament were incandescent at the attitude of the troika (the IMF, the European Union, and the European Central Bank). There was no way that they were going to support any deal along the lines of further austerity and neoliberal measures demanded by the troika. So the Greeks have fired a warning shot across the bows of the IMF and the Eurogroup, hinting that they may prefer to default rather than be forced into further concessions.

According to sources for the Daily Telegraph, the IMF representative in the negotiations, Poul Thomsen, has “pushed the austerity agenda with a curious passion that shocks even officials in the European Commission, pussy cats by comparison.”

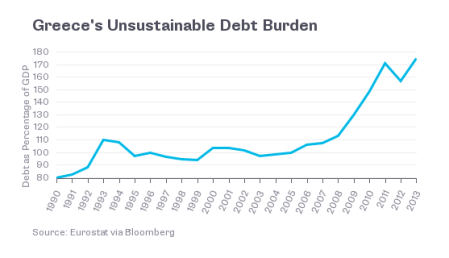

The IMF is demanding further sweeping measures of austerity at a time when the Greek government debt burden stands at 180% of GDP, when the Greeks have already applied the biggest swing in budget deficit to surplus by any government since the 1930s and when further austerity would only drive the Greek capitalist economy even deeper into its depression.

As the Telegraph summed it up: “six years of depression, a deflationary spiral, a 26pc fall GDP, 60pc youth unemployment, mass exodus of the young and the brightest, chronic hysteresis that will blight Greece’s prospects for a decade to come.”

The Syriza government has already made many significant retreats from its election promises and wishes (see Syriza’s latest proposals here). Many “red lines” have been crossed already.

It has dropped the demand for the cancellation of all or part of the government debt; it has agreed to carry through most of the privatizations imposed under the agreement reached with the previous conservative New Democracy government; it has agreed to increased taxation in various areas; it is willing to introduce “labor reforms”; and it has postponed the implementation of a higher minimum wage and the re-employment of thousands of sacked staff.

But the IMF and Eurogroup wanted even more. The troika has agreed that the original targets for a budget surplus (before interest payments on debt) could be reduced from 3–4 percent of GDP a year up to 2020 to 1 percent this year, rising to 2 percent next year, etc. But this is no real concession because government tax revenues have collapsed during the negotiation period.

At the end of 2014, the New Democracy government said that it would end the bailout package and take no more money because it could repay its debt obligations from then on, as the government was running a primary surplus sufficient to do so. But that surplus has now disappeared as rich Greeks continue to hide their money and avoid tax payments and small businesses and employees hold back on paying, uncertain about what is going to happen. The general government primary cash surplus has narrowed by more than 59 percent to €651 million in the four-month period of 2015 from 1.6 billion in the corresponding period last year.

The Syriza government has only been able to pay its government employees their wages and meet state pension outgoings by stopping all payments of bills to suppliers in the health service, schools, and other public services. The result is that the government has managed to scrape together just enough funds to meet IMF and ECB repayments in the last few months, while hospitals have no medicines and equipment, schools have no books and materials, and doctors and teachers leave the country.

Even Ashoka Mody, former chief of the IMF’s bailout in Ireland, has criticized the attitude of his successor in the Greek negotiations:“Everything that we have learned over the last five years is that it is stunningly bad economics to enforce austerity on a country when it is in a deflationary cycle. Trauma patients have to heal their wounds before they can train for the 10K.”

The final red lines have been reached. What the Syriza leaders finally balked at was the demand by the IMF and the Eurogroup that the government raise the VAT on electricity by 10 percentage points, directly hitting the fuel payments of the poorest; and also that the poorest state pensioners have their pensions cuts so that the social security system could balance its books.

Further down the road, the troika wants major cuts in the pensions system by raising the retirement ages and increasing contributions. The Syriza leaders were even prepared to agree to some VAT rises and pension “reforms,” but the two specific demands of the troika appear to have been just too much.

As Mody put it: “I am frankly shocked that we are even having a discussion about raising VAT at all in these circumstances. We have just seen a premature rise in VAT knock the wind out of a country as strong as Japan.”

As for pensions, they have already been slashed under previous bailout agreements with the Troika. Main pensions have been slashed 44–48 percent since 2010, reducing the average pension to €700 a month. Contributors to a supplementary scheme receive a top-up averaging €170 a month. About 45 percent of Greek pensioners receive less than €665 monthly — below the official poverty threshold.

The troika wants more. It is pressing for across-the-board cuts in both main and supplementary pensions; the abolition of a special monthly stipend for pensioners receiving the lowest benefits; an increase in the retirement age to sixty-seven; the ending of special arrangements that allow working mothers and people in “dangerous” occupations to retire early on full pensions; and the merger of dozens of sectoral pension funds into three main funds.

The horrible truth is that none of these further cuts would be necessary if the troika had just cancelled some of Greece’s public sector debt back in 2012 when the debt was “restructured.” Instead, the banks of Germany and France were paid off for their holdings of Greek government bonds with just a small “haircut,” and the debt burden then fell on the shoulders of the new eurozone bailout institutions and Greece’s own pension funds.

Greece’s pension funds lost an estimated €25 billion of reserves that were held in government bonds as a result of the debt restructuring. They have been unable to replenish them. Meanwhile, contributions to the system fell sharply as unemployment soared above 25 percent and outlays rose sharply as more than sixty thousand public sector workers opted for early retirement, fearing their jobs would soon be eliminated.

The reality is that Greece can never pay back these loans. Greek capitalism is in a deep depression and experiencing deflation. The OECD has just slashed its Greek GDP estimates to 0.1% in 2015 from 2.3% in its previous forecast published last November. So the debt burden is rising not falling despite (and partly because of) austerity. The IMF recognizes this and suggests that the Eurogroup agree to a haircut on its loans (while the IMF still expects full repayment of its loans).

The Eurogroup has already agreed that no repayments on its debt need be made until 2020, but won’t agree to a debt haircut (yet). And both the IMF and the Eurogroup want to cut the debt in the meantime and thus are demanding more austerity measures.

Syriza has made a very modest proposal to cut the debt burden in the future, but this proposal has been ignored by the troika, at least until Greece capitulates on the current bailout terms.

The Greek government is running out of cash to pay back the IMF and the ECB, and very big repayments are scheduled for July and August. It will definitely run out of money by the end of this month, when the choice will be between paying the IMF the bundled-up debt or paying government workers their wages.

The cruel irony is that if Syriza agrees to the demands of the troika on VAT, pensions, and other austerity measures, the money it receives under the existing bailout agreement of €7.2 billion (and some €1.9 billion in held-back ECB profits on Greek bonds) would just be immediately transferred back to the IMF and the ECB. Nothing would touch the sides of the Greek government to pay its employees or suppliers.

So even if there’s a deal soon (and it will have to be done probably by June 18, when the next euro summit takes place, so that the German and Greek parliaments have time to endorse the deal), almost immediately negotiations will have to be concluded on a new package so the Greeks can make repayments to the IMF (scheduled up to April 2016) and to finance any deficits and interest payments down the road. Greece will be tied into another five years of austerity.

The late-night decision of the Syriza leaders shows that they have reached the end of their tether and it will not be possible to persuade their own party to accept troika demands that would mean accepting in full everything that the previous New Democracy government agreed to. If that happened, what would be the point of a Syriza government, supposedly elected to reverse austerity?

According to opinion polls, the Greek people still overwhelmingly want to stay in the eurozone and they still give strong support to Syriza in polls, but support for the government’s negotiations with the troika has been fading. The people want a deal but they don’t want austerity. This appears to be an unresolvable conundrum.

What next then? Well, assuming that the troika does not blink and drops its latest demands, and assuming that the Syriza leaders do not capitulate, then default on the debt will take place at the end of this month. The government will have to take steps to introduce capital controls to stop the flow of funds out of the banks and abroad, already sizable in the last few months.

In my view, Syriza would finally have to grasp the nettle and take over the banks; reverse all austerity measures; launch a program for state investment and jobs and appeal directly to labor movements in Europe for a continent-wide program of action over the heads of the euro leaders. Up to now, Syriza has failed to do this, but it is not too late to start at ten minutes past midnight.

As I said in a post last March:

The issue for Syriza and the Greek labour movement in June is not whether to break with the euro as such, but whether to break with capitalist policies and implement socialist measures to reverse austerity and launch a pan-European campaign for change. Greece cannot succeed on its own in overcoming the rule of the law of value.