I Love Man of Steel and I’m Not Sorry

In Man of Steel, Superman returns to his Popular Front roots.

There’s a special place in hell for those who say nice things about Zack Snyder’s films. Slavoj Žižek doomed himself to such a fate with his review of 300, which positioned Snyder’s supposedly racist, ‘roided-out homoerotics as a celebration of revolutionary discipline. I never saw 300, but I admired Žižek’s willingness to troll like that.

So when I tell you that I not only appreciated, but loved Snyder’s Man of Steel, believe me, I can smell the flames singing the skin off my feet. But I’m sorry to say, this is the big dumb Wagnerian movie I’ve been waiting for. It’s Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen on a quarter of a billion dollars.

So far, I’m seeing a lot of “been there, done that” reviews for Man of Steel. Are you kidding me? Every comic book movie is “been there, done that.” The format was played out fifteen years ago! Because let’s face it: it’s a pretty lame genre. These movies suck. Zombie-apocalypse films have a better signal-to-noise ratio.

I guess we can start the clock at Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman, which is all but unwatchable today (seriously: just try it). What are the classics? Anyone? We’re offered only two variations in the genre, each one equally dull: gritty ‘realism’ and bright, poppy camp. Only Ang Lee’s Hulk stands out with its extra helpings of grizzled Nolte and nuked-out Monument Valley vistas. But everybody hated it. Oh well.

Without a doubt, Man of Steel is the only one of these I’ve wanted to freeze-frame and gawk at. Check out the Kryptonian production design: the wiry headdresses, the floating liquid-metal sonogram pod, the helmets made out of electric ribbed condoms, the way their lasers crash into bodies in big cavities of blue fire, the underwater communal embryonic sac (apparently Goyer and Snyder are up on their Shulamith Firestone). All that’s missing is some of H. R. Giger’s creepy phalluses and hidden vulvatics and we’re at Dune levels of weirdness.

In fact, Eisenstein and Lynch’s Dune are films I kept thinking about all throughout Man of Steel. The Kryptonian council at the beginning is just as alien, sinister and cooly regal as the Tsarist court of Ivan the Terrible. Even Superman’s fever dream of extinction has him sinking into a pile of skulls like a Chuck E. Cheese ball pit. These are things you won’t see in Raimi’s Spider-Man flicks let alone the wildly overrated Iron Man movies. I enjoyed it all like I enjoyed Gangs of New York: it’s so damn interesting looking I don’t really care about anything else. Luckily, unlike Gangs of New York, most of the rest actually works.

Snyder shares many of the strengths and weaknesses of David Fincher. Both got their start in filmmaking on the craftsman side of things (Fincher, FX work and music videos; Snyder, commercials). Both excel at seamlessly integrating CGI into the cinematic palette. Both know how to composite and light a shot so perfectly and so dimly that every figure on the screen seems to be carved out of the background. Their films have a tactility that’s increasingly rare in the digital era; both refuse to surrender texture to clarity and high-definition. You certainly won’t find that quality in Joss Whedon’s massively overrated The Avengers, which is like watching a bunch of Jeff Koons sculptures fly around you at 200 mph.

Maybe there is something to Snyder after all? I’ve only seen his Dawn of the Dead remake, which I liked, and Watchmen, which I enjoyed in small patches. In his effusively pro-Man of Steel review, noted contrarian and right-wing troll Armond White calls Snyder’s animated talking-owl movie Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga’Hoole “a masterpiece, I promise you.” Now that’s a promise.

I doubt Snyder will ever deliver something as brilliant as Fincher’s Zodiac, the best film to come out of Hollywood in the twenty-first century. Or as twisted as Gore Verbinski’s Pirates of the Caribbean movies. Snyder’s a brilliant stager, a craft-mimic who can give us steady, icy Kubrickian distance and shaky, Malicky waves of grain sometimes all within the same scene.

Let’s just say it: Snyder is all surface. And that’s okay. We’ve had some great directors who were proudly and staunchly “all surface” (Anthony Mann springs to mind). I saw another critic say that Snyder’s “no auteur.” Though, really, what the fuck does that even mean in the age of $225 million movies? The last time that much money was funneled into a truly singular, uncompromised vision, we got the Star Wars prequels. If that’s mega-budget independent filmmaking (and they technically were “independent”), I’ll take mega-budget movie-by-committee, thanks. Great cinema as the result of a single, uncompromised genius is just as much a bourgeois illusion as the idea of a billionaire having “earned” his wealth.

I’ve heard a lot of grumbling about the last hour of action. It drags, it goes on too long, etc. In any other comic book movie, I’d always agree. Can’t really think of a truly exhilarating action sequence in any of these movies — the opening to the third Nolan Batman movie, maybe. But that’s because the action in most comic book movies sucks. As Eileen Jones pointed out in her great review of the last Batman movie, the “balls-to-the-wall” mass street fight scenes just looked staged and dopey, like a bunch of C-list MMA fighters showing off at the edge of the screen for $100 a day and a modest per diem.

But here, Snyder goes out of his way to keep every single punch, jump and crash interesting. It’s probably the first time I’ve enjoyed a CGI-throw-down. Somehow, Snyder makes the physics of the film feel real — one of the few decent skills Hollywood’s picked up from video games. When Superman punches the ground to take-off in flight for the first time, we intuitively understand how it works. We can feel it despite the fact that it makes no sense whatsoever.

And the heat vision! In every other adaptation, it’s Superman’s lamest power. Two little laser pointers that microwave-upon-impact. You could practically see the underpaid animators scribbling them in across the frame. But here, it’s like watching eyeballs vomit lava. Watching Zod strafe an office building with his plasma-pupils reminded me of all those gruesome Vietnam War reels of GI’s awkwardly steadying flamethrower-spray into tunnels. It’s genuinely horrifying.

Best of all, Snyder and Goyer’s Man of Steel is a reminder that Kal-El, who debuted in 1938, is a product of the Popular Front era. Appropriately enough, I went to the megaplex with a card-carrying liberal wonk.

Whereas Bruce Wayne’s Third World tourism in the first Nolan Batman flick ends with a glass of bubbly and a ride home on a private jet, in Man of Steel, Clark’s spent the past years working blue collar jobs all over North America, tending bar and working on fishing vessels. It’s crucial that Lois Lane pieces together his identity through testimonies of his fellow proletarians: “He was a good worker,” says one of them. The New York Times’s Manohla Dargis accurately casts this as a return to a Depression-era, somewhat renegade Superman:

The oil platform is most notable for the workingmen Superman rescues, laboring brothers to the trapped coal miners who figure into one of his first comic-book outings in 1938. One of the pleasures of the Christopher Reeve “Superman” series, which took off in 1978 and bottomed out in 1987, was how the movies managed to be both charmingly old-fashioned and of their contemporary moment. There are a number of overt references to the past in “Man of Steel,” a title that itself summons up America’s lost industrial history. There’s even a scene in which Jor-El narrates Krypton’s rise and calamitous fall using immersive, metallic-gray images that morph and scroll across the frame like an animated version of a W.P.A. bas-relief mural.

As Superman’s bio-dad explains, Kryptonians are genetically engineered in vitro with the “birthing matrix” which Zod wants so desperately to preserve. But while that might sound like typical anti-collectivization paranoia, it’s where Kal-El really flashes his Red.

Before they’re even born, it’s already decided which Kryptonians will be “a soldier, a worker, a scientist.” Kal-El’s parents conceived au naturel as a way of liberating their son from this genetically-induced class destiny. When Superman destroys the birthing matrix, he’s really demolishing the whole rigid class structure of Krypton.

As best-selling comic book writer Grant Morrison put it in his memoir:

Superman began as a socialist, but Batman was the ultimate capitalist hero, which may help explain his current popularity and Superman’s relative loss of significance. Batman was a wish-fulfillment figure as both filthy-rich Bruce Wayne and his swashbuckling alter ego. He was a millionaire who vented his childlike fury on the criminal classes of the lower orders. He was the defender of privilege and hierarchy. In a world where wealth and celebrity are the measures of accomplishment, it’s no surprise that the most popular superhero characters today — Batman and Iron Man — are both handsome tycoons.

Chris Nolan and David Goyer — who worked on Man of Steel as producer and screenwriter, respectively — took a lot of shit for their right-wing Batman flicks. But after seeing how easily they transitioned to the left for the man in the red BVD’s, it’s clear that reactionary Batman was always the only way to go. They actually got that right. Reaction is the essence of Batman. It’s built right into his DNA.

I’m ready to surrender that one. Looking back, the Nolan movies are best enjoyed if you just root for Ra’s and Bane and give up on the weasely richkid. Who would deny that Blackwater/Xe’s Erik Prince is anything other than the real life Bruce Wayne? Just like at the end of The Dark Knight, real-life Bruce was also forced to go into hiding (Abu Dhabi) simply for “keeping us safe.”

Kal-El agonizes over the fate of humanity. But Bruce Wayne, like Nixon, mopes around in dark rooms, fretting exclusively about the bourgeoisie of Gotham. Or maybe he’s more like Bloomberg. Did someone snatch an iPad out of an NPR tote bag in East Gotham? Better send out a stop-and-frisk squad and lay down some bike lanes to price out The Poors. It’s astonishing and very telling that even a casual Batman reader can rattle off the names of at least two fictional Gotham prisons without blinking (Arkham Asylum and Blackgate, of course).

Man of Steel’s dose of right-wingery comes in the form of Michael Shannon’s Zod, surely one of the great Termite Art performances of the past few years. Just listen to his mumbly bark as he shouts “heresy!” after he finds out that Supe’s dad is into barebacking. Goddamn, do I love Michael Shannon. He’s one of the best we got. And his Zod is far more sympathetic than the typical cartoon brownshirts we get from these capes-and-tights flicks. Does anyone even remember what Loki’s beef was in The Avengers? Something about a Rubik’s cube?

I felt sorry for Zod. He spends much of the movie chasing after the precious “birthing chambers” necessary to regenerate his race and decrying the extinction of the Kryptonian people (and their distant colonies) even as he begins to terraform Earth and it’s inhabitants into dust. We find out that he’s spent the past decades hopping across the universe, digging up and salvaging the remnants of lost Kryptonian colonies long after his home planet was destroyed. How can we not pity him?

Like Prometheus, Man of Steel is another blockbuster film that presents us with a more powerful humanoid species that wants nothing more than to stamp our miserable asses out of the universe. I can only assume we’re working out some massive collective self-loathing at the megaplex.

If anything, Shannon’s Zod reminded me of an ultra-right Likudnik. The big, loud climax of the movie comes when Zod sends two gigantic robo-drills to terraform Earth into a New Krypton, which would of course end with the total extinction of the human race. But Zod’s not too worried about that. He all but says “can’t make Space-Zion without breaking a few eggs.”

For a character dreamed up by two Jewish boys in Cleveland as a kind of Moses-cum-Christ figure, it’s bizarre that no one’s made this connection yet. Which goes to show you just how off-the-radar the plight of the Palestinians is for both mainstream America as well as our circle of liberal film critics.

Zod’s fervent Krypto-Zionism versus Kal-El’s pluralism and universalism reminded me of a passage from Eric Hobsbawm’s memoir:

As a historian I observe that, if there is any justification for the claim that the 0.25 per cent of the global population in the year 2000 which constitute the tribe into which I was born are a ‘chosen’ or special people, it rests not on what it has done within the ghettos or special territories, self-chosen or imposed by others, past, present or future. It rests on its quite disproportionate and remarkable contribution to humanity in the wider world, mainly in the two centuries or so since the Jews were allowed to leave the ghettos, and chose to do so. We are, to quote the title of the book of my friend Richard Marienstras, Polish Jew, French Resistance fighter, defender of Yiddish culture and his country’s chief expert on Shakespeare, “un peuple en diaspora.“

While the trailers try and portray Zod’s hatred of Kal-El as another tale of bloodline vengeance against Superman’s biological father Jor-El (Russell Crowe), it’s far more interesting than that. Here, the McGuffin is the entire genetic ‘source code’ of the Kryptonian race tucked away inside of Kal-El’s cellular structure by his father. Zod needs Kal-El, dead or alive, to rebuild Krypton. It’s only after Superman has demolished any possibility of that ever happening that Zod truly goes apeshit and even then, there’s an eerie control to his rage. I cheered watching him gallop up the side of a building on all fours like the pitbull from No Country for Old Men, ready to tear into Superman’s leg. I love you, Terence Stamp, but this is definitely not your flick.

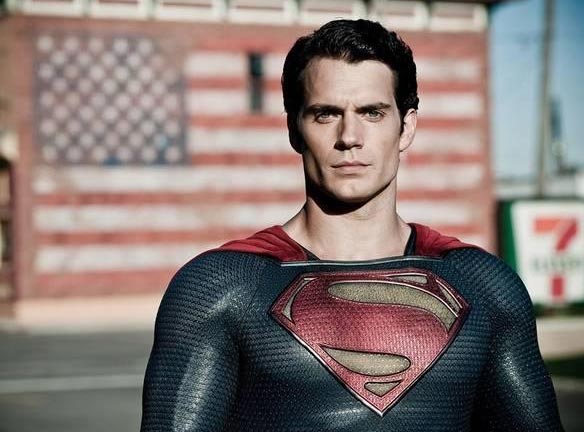

And for all the flack Henry Cavill is taking for a Superman performance that mostly consists of finding new ways to aim and contort his jawline, that jawline speaks volumes. Proper-aiming-of-jawline is like 80% of the job for Hollywood’s great leading men.

Here’s an example. There’s a scene early on, a Superman trademark at this point, where a redneck tries to pick a fight with Clark. Instead of just a noble turning-of-the-cheek or a look of restrained rage, it’s consternation, bafflement. Clark’s face screams, why is this happening? Why would you do this to me? Why the fuck do I have to live in a world full of hairless chimpanzees constantly trying to cock-slap the next guy?

It’s a reminder of what really makes that first moment of casual cruelty so horrible for junior high males. Not the shame or embarrassment, but the realization that “wait, it’s really going to be like this?” Sorry, Clark, but in our hyper-capitalist hellhole, it really is going to be like that.

He looks like he’s about to cry. It’s a reminder of his permanent exile with us, the hairless chimps always looking for a chance to brain the other guy. Clark walks away but has his revenge: he impales the redneck’s semi with a half dozen tree trunks, leaving him to contemplate the awe-inspiring creation before him like some Houston fratboy gawking at one of Eduardo Chillida’s massive twists of iron. He doesn’t understand it, he’s maybe even a little afraid of it, but he knows it’s better than him.

Every Superman story has run through “the puberty years,” where Clark adjusts to funny feelings and hair in new places. But in the Reeves’s Superman flicks, Clark’s problem is holding back. In Man of Steel, Clark spends his childhood pulverized by seeing, hearing and feeling everything around him. He’s suffocated by every sensation. He can’t tune anything out. He has panic attacks. It’s Superman for the Adderall generation.

His difficulty in processing a thousand different sensations mirrors the much-despised Millennials’ inundation into a world of infinite communication, a world of information tugging him or her a thousand different directions at once. When Zod first removes his helmet on Earth and his Kryptonian cells start to take it all in, he’s crippled by it. Humans — Clark’s adopted parents — taught him how to cope. But for Zod, who wants nothing more than to Terraform the earth into his Krypto-Zion, empathizing with the “other” is lethal.

Kevin Costner’s excellence as Pa Kent is a reminder that the problems with his career have always been one of misallocation, not a lack of talent. (Eliot Ness? Robin Hood? Aqua-Mad Max? What were they thinking?) Amy Adams is good too, she seems to have dialed down the perk and pluck this time around. Even the casting of Diane Lane as Ma Kent works. Her grey-streaked waifishness reminded me less of middle-age Under the Tuscan Sun and more of a midwestern mom with a pack of menthols in her purse.

In the lefty blogosphere, I’ve seen a few complaints about Man of Steel’s tie-in campaign with the National Guard. The movie is certainly far from critical about US militarism. Sure, it ends with Superman punting a drone, but like most Hollywood drone-cameos, it’s just a half-baked stab at social relevance. Here, like in the Silver Age Superman, Kal-El enters into an alliance (albeit an uneasy one) with the US military.

But I’d have to ask: what do you expect? This is Hollywood. This is bourgeois art. Are we shocked by the over-the-top Stalinist jingoism of Eisenstein’s glorious Alexander Nevsky (certainly the Man of Steel of its day)? I’m reminded of what Michael Rogin said about the premiere of Independence Day at the Clinton White House: “Hollywood and Washington, twin capitals of the American empire and seats of its international political economy, collaborated to promote the movie that filmed their destruction.”

But to be honest, this kind of thing has never bothered me. I just expect it. What was Richard Donner’s cornball late seventies Superman but the liberal wing of the same great tide of whitebread normalcy that ushered in Ronald Reagan two years later? As the great Marxian film critic Robin Wood once said when comparing Stalinist cinema to Hollywood:

The “democratic” bourgeois ideology is another matter altogether: in order to justify its claim to being democratic, it has to accommodate so much, to be prepared to bend and stretch in so many directions, that contradiction and complexity are its ineradicable qualities.

Superhero movies are now one of our most profitable national exports, along with Silicon Valley, militarism and Big Pharma. But I’ll admit that church scene with the priest sure was dopey. Papists? In Kansas? Are you kidding me? Supes goes into a Kansas church he’s liable to get recruited into heat visioning a Planned Parenthood if he’s not careful.

But when the film ends with Clark joining the urban creative class, I almost cried. No, Clark! You’ll spend the rest of your thirties as a glorified copy-editor. At absolute best, you’ll write a list-icle or two. I can see it now: The Daily Planet’s “Top-10 Emu Photobombs” by Clark Kent. Truly a hero for our times.