Debt: The First 500 Pages

We need more grand histories. But 5,000 years of anecdotes is no substitute for real political economy.

David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years is an ambitious book. The title tells us that, and so does its author. At the anthropology blog Savage Minds, Graeber reports that a friend, on reading a draft, told him, “I don’t think anyone has written a book like this in a hundred years.” Graeber is too modest to take the compliment, but admits his friend has a point. He did intend to write “the sort of book people don’t write any more: a big book, asking big questions, meant to be read widely and spark public debate, but at the same time, without any sacrifice of scholarly rigor.”

So it is a book in which endnotes and references make up almost 20 percent of the page count, but also one that makes liberal use of contractions and includes the occasional personal anecdote. It is, as Graeber says, “an accessible work, written in plain English, that actually does try to challenge common sense assumptions.” The style is welcome, akin to that of the best interdisciplinary scholarly blogs (like Crooked Timber, where Debt has been the subject of a symposium): clear, intelligent, and free of unexplained specialist jargon.

It has had great success in finding a popular audience and accumulated glowing press reviews: “one of the year’s most influential books,” “more readable and entertaining than I can indicate,” “a sprawling, erudite and provocative work,” “fresh . . . fascinating . . . not just thought-provoking, but also exceedingly timely,” “forced me to completely reevaluate my position on human economics, its history, and its branches of thought.” It has also found the desired political audience: Graeber became a guru of the Occupy movement, not only as a participant but as an intellectual presence, his book in encampment libraries everywhere.

Debt, then, does not need any more kind words from me. It’s enough to say that there is a lot of fantastic material in there. The breadth of Graeber’s reading is impressive, and he draws from it a wealth of insightful fragments of history. The prospect of a grand social history of debt from a thinker of the radical left is exciting. The appeal is no mystery. I wanted to love it.

Unfortunately, I found the main arguments wholly unconvincing.

The very unconvincingness poses the question: What do we need from our grand social theory? The success of the book shows there is an appetite for work that promises to set our present moment against the sweep of history so as to explain our predicament and help us find footholds for changing it. What is wrong with Graeber’s approach, and how could we do better?

Debt is about much more than debt. A history of debt, Graeber writes, is also “necessarily a history of money.” The difference between a debt and an obligation is that the former is quantified and needs some form of money. Money and debt arrived on the historical scene together, and “the easiest way to understand the role that debt has played in human society is simply to follow the forms that money has taken, and the way money has been used, across the centuries.” But to make debt the guiding thread of your history of money gives “necessarily a different history of money than we are used to.”

And a history of money must also be a history of nothing less than social organization — not because monetary exchange has always been so central to social organization, but precisely because it has not. Graeber uses such a wide historical and geographical canvas because it shows us the sheer variety of shapes in which society has been formed, and this broadens our vision of the possible. The history of debt and money gives us “a way to ask fundamental questions about what human beings and human society could be like.”

Throughout the book, Graeber presents himself as a maverick overturning convention. Partly, his maverick status rests on his politics — he is the anarchist saying things about debt, money, markets, and the state that the powers-that-be would rather not look squarely in the face. But largely his argument is a move in an interdisciplinary struggle: anthropology against economics.

Economics, he complains, “is treated as a kind of master discipline,” its tenets “treated as received wisdom, as basically beyond question.” And yet it is a kind of idiot discipline: its assumptions have been shown again and again to be false, but it keeps on keeping on, secure in its dominance like a stupid rich man sought out by sycophants for his ideas on the issues of the day.

If there is one argument that provides a thread through the whole narrative, it is Graeber’s view that money has its origins in debt and not exchange, and that economics has always got this the wrong way around. He establishes (1) that economics texts typically present the need for money as rising out of the inefficiencies of barter; and (2) that nevertheless there is no historical record of money rising out of a prior system of generalized barter.

Graeber considers the “myth of barter” so central to economics that to point out its status as myth is to pull out the Jenga block that brings the whole structure down. Economics has little worth saying on money, and so economists can safely be pretty much ignored for the rest of the book:

“Can we really use the methods of modern economics, which were designed to understand how contemporary economic institutions operate, to describe the political battles that led to the creation of those very institutions?” Graeber’s answer is negative: not only would economics mislead us, but there are “moral dangers.”

This is what the use of equations so often does: make it seem perfectly natural to assume that, if the price of silver in China is twice what it is in Seville, and inhabitants of Seville are capable of getting their hands on large quantities of silver and transporting it to China, then clearly they will, even if doing so requires the destruction of entire civilizations.

Economics’ lack of moral sense is not only dangerous, corrupting our sensibilities, but prevents it from understanding the social reality it pretends to describe. It starts from the false premise “that human beings are best viewed as self-interested actors calculating how to get the best terms possible out of any situation, the most profit or pleasure or happiness for the least sacrifice or investment.”

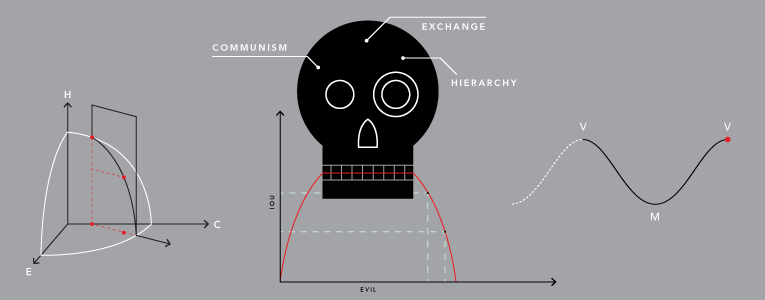

Graeber’s alternative is to recognize the diversity of motives that guide people’s economic interactions. He proposes that there are three “main moral principles” at work in economic life: communism, exchange, and hierarchy. “Communism” describes sharing relationships based on the principle of “to each according to their needs, from each according to their abilities.” “Exchange” relationships are based on reciprocity and formal equality, while “hierarchical” relationships are unequal and tend to work by a logic of social precedent rather than reciprocity.

These are not different kinds of economies, but principles of interaction present in all societies in different proportions: for example, capitalist firms are islands of communism and hierarchy within a sea of exchange. We can untangle history by looking at the shifting boundaries between the different kinds of relationships. Debt shakes things up by inserting hierarchical relationships into the sphere of exchange — an “exchange that has not been brought to completion,” which suspends the formal equality between parties in the meantime. If the meantime stretches out because the debt becomes unpayable, the equality may be permanently suspended and the relationship become a precedent-based hierarchy — though Graeber warns against making too much of this, which would fall into the economists’ trap of assuming reciprocal exchange to be the baseline against which all other relationships should be measured.

The most simplistic renditions of neoclassical economics may reduce all human interactions to self-interested exchange. But the idea that society is made up of different but interdependent levels is hardly new in social theory. Neither is Graeber’s view that to talk of a society as a unit may be misleading, since people are involved in social interactions across multiple horizons that may not fit together into a coherent whole. One could cite, for example, Althusser’s “decentered structure” and Michael Mann’s “multiple overlapping and intersecting sociospatial networks of power.” Indeed, it could almost be seen as a constant in social theory since the classics.

But most of these other approaches to grand socio-history differ from Graeber’s in treating these levels as structures, and not simply as the practices that create them. They are made up of complex, evolving patterns of relationships that cannot be reduced to or derived from deliberate individual or interpersonal action. They emerge, as Marx put it, “behind the backs” of the very people who collectively create them. They become the social contexts that frame our actions, the circumstances not of our choosing within which we make history. They are collective human products, but not of ideological consensus — rather, they are the outcome of often competing, contradictory pressures.

Graeber, in contrast, stays mainly at the level of conscious practice and gives a basically ethical vision of history, where great changes are a result of shifting ideas about reality. I cannot do justice here to the whole sweep of his history, but let’s look at his section on the rise of capitalism. If we can’t use modern economics to explain the rise of the modern institutions it is designed to study — a fair point — what is Graeber’s alternative?

First, we get a story about Cortés and the conquistadors. Economics would have us “treat the behavior of early European explorers, merchants, and conquerors as if they were simply rational responses to opportunities.” Graeber replaces this explanation with another: they were especially greedy, and “we are speaking not just of simple greed, but of greed raised to mythic proportions.” The greed of the Europeans is contrasted with the inscrutable warrior honor of Moctezuma, who would not object when he saw Cortés cheat at gambling. Also, Cortés and his fellows were drowning in debt, and so was Emperor Charles v, who sponsored his expeditions.

Meanwhile, back in Europe, Martin Luther is coming to terms with usury and urging rulers to “compel and constrain the wicked . . . to return what they borrow, even though a Christian ought not to demand it, or even hope to get it back.” Graeber tells us the story of the Margrave Casimir of Brandenburg, who burned and pillaged his way through his own realm to put down one of the great peasant rebellions of 1525. Casimir, too, was deep in debt and had farmed out offices to his creditors, who squeezed the population into revolt. For Graeber, the violence of Cortés and Casimir “embod[ies] something essential about the debtor who feels he has done nothing to be placed in his position: the frantic urgency of having to convert everything around oneself to money, and rage and indignation at having been reduced to the sort of person who would do so.”

From there we are off to jolly, rustic early modern England, to witness feudalism’s replacement by capitalism. Graeber intends to “upend our assumptions” about the rise of capitalism as the extension of markets. English villagers were quite happy with market transactions in their place, as part of a moral economy of mutual aid. This is symbolized by the fact that they didn’t use much gold and silver, but tended to carry on everyday transactions on credit, based on mutual trust. But this economy came to be undermined by the encroachment of a cash-focused economy that criminalized debt. This was a deliberate effort by a coalition of the wealthy and the state, who were at the same time foolishly deluded into believing that the real nature of money lay in the intrinsic value of precious metals.

The story of the origins of capitalism, then, is not the story of the gradual destruction of traditional communities by the impersonal power of the market. It is, rather, the story of how an economy of credit was converted into an economy of interest; of the gradual transformation of moral networks by the intrusion of the impersonal — and often vindictive — power of the state.

And that is Graeber’s explanation for the rise of capitalism. Evil: the root of all money.

Of course, there is a lot of insight in the detail, fascinating interpretations of the writings of merchants and political philosophers. Graeber is a wonderful storyteller. But the accumulation of anecdotes does not add up to an explanation, and certainly not one that would overturn the existing wisdom on the subject, conventional or otherwise. It is a story told almost entirely in the realm of political and moral philosophy, and told essentially from a populist liberal or even libertarian perspective: it was the state and big business stepping all over the little guys and their purer exchange relationships.

Graeber approvingly cites the great social historian Fernand Braudel’s distinction between markets and capitalism (which draws on Marx) — the former being about exchanging goods via money, and the latter about using money to make more money. For Braudel, capitalism is the domain of the big merchants, bankers, and joint stock companies that feed off the market and reorganize it. For Graeber, the easiest way to make money with money is to establish a monopoly, so “capitalists invariably try to ally themselves with political authorities to limit the freedom of the market.”

But Graeber is no Braudel. The latter’s epic history of the rise of capitalism (with the luxury, it must be said, of covering just four centuries in three volumes) also takes a pointillistic approach, but is full of actual data, diagrams, and maps, organized to give us a real sense of the material conditions of life and the operations of economic networks. Graeber stays almost entirely within the domain of “moral universes” and discourse. We don’t get a sense of just how the moral economy of Merrie England was undermined, except that the powers-that-were didn’t get it, didn’t like it, and imposed their own morality somehow. He engages very selectively with the literature on the “rise of capitalism” — how else to explain his portrayal of the news that sophisticated banking and finance long predated the rise of the factory system and wage labor as if it were a challenge to all preconceptions? This “peculiar paradox” has been a commonplace of the Marxian literature since Marx.

In place of a materialist economic history, Graeber’s 5,000 years are organized according to a purported cycle of history in which humanity is perpetually oscillating between periods of “virtual money” — paper and credit-money — and periods of metal money. The emergence and rise of capitalism up to 1971 has to be shoehorned into this quasi-mystical framework as a turn of the wheel back toward metallism. The spectacular development of the capitalist banking and financial system in this period, seemingly “a bizarre contradiction” to the overarching frame of the narrative, turns out to be just what proves the rule — for just as monetary relations began to sprout in all kinds of weird and wonderful directions we might call “virtual money,” governments redoubled their commitment to the metallic base, and economists developed their barter theories of money as king of commodities.

Let’s turn now to what Graeber thinks this all means for debt and money today — since, in his reading, our present chaos reflects another revolution of the wheel back to virtual money.

In place of the “myth of barter,” Graeber champions alternative stories which economists have kept “relegated to the margins, their proponents written off as cranks.” These are the state and credit theories of money, which he rightly sees as overlapping.

Credit theorists insist that “money is not a commodity but an accounting tool”:

In other words, it is not a “thing” at all. You can no more touch a dollar or a deutschmark than you can touch an hour or a cubic centimeter. Units of currency are merely abstract units of measurement, and as the credit theorists correctly noted, historically, such abstract systems of accounting emerged long before the use of any particular token of exchange.

What do these units of measurement measure? Graeber’s answer is: debt. Any piece of money, whether made of metal, paper, or electronic bits, is an iou, and so “the value of a unit of currency is not the measure of the value of an object, but the measure of one’s trust in other human beings.”

How is trust in particular kinds of money established? Clearly we don’t accept just anyone’s iou in payment. This is where the state theorists of money, the chartalists, come in. Graeber draws on what is still the classic statement of chartalism, G. F. Knapp’s State Theory of Money (1905). States, Knapp argued, have historically nominated the unit of account, and by demanding that taxes be paid in a particular form, ensured that this form would circulate as means of payment. Every taxpayer would have to get their hands on enough of the arbitrarily defined money, and so would be embroiled in monetary exchange.

Economists have never been able to face up to these arguments, says Graeber, because they would undermine the precious myth that money emerged naturally out of private barter, and make all too visible the hand of the state in the construction of markets. Credit and state theorists of money have therefore always been dismissed as cranks.

A big exception here, as Graeber acknowledges, is Keynes. The opening chapter of his Treatise on Money (1930) is heavily influenced by Knapp’s book, which had been translated into English only a few years before. Keynes writes that the state enforces contracts denominated in money, but more importantly, “claims the right to declare what thing corresponds to the name, and to vary its declaration from time to time,” a right “claimed by all modern States and . . . so claimed for four thousand years at least.”

For Keynes, part of the appeal of chartalism was surely the political implication: if states created money, they could do what they liked with their creation; there was no need for superstitious attachment to that barbarous relic gold. The foolhardy attempt to restore sterling to its pre–World War I parity with gold had wreaked havoc on 1920s Britain, so Knapp’s was a message of major contemporary significance dressed in the ancient robes of the Kings of Lydia.

For an anarchist like Graeber, the appeal of a state theory of money is precisely the opposite: money is a creature of the state, and so tainted. But the then-orthodox view Keynes enlisted chartalism to oppose — the notion that money is naturally a commodity, and that states break the link to metal at our peril — is now the doctrine of cranks.

The idea that money may be backed by nothing more than the writ of a state functionary and yet function perfectly well is hardly a radical notion anymore. It is, in fact, typical in monetary economics textbooks. (See, for example, the opening chapter of Charles Goodhart’s standard text Money, Information and Uncertainty.) Yet it doesn’t seem to have made much difference to monetary theory. Texts have no problem acknowledging that money is not a commodity, and then going on to claim that money exists because barter is inefficient.

The reason, to be blunt, is that unlike Graeber’s critique, not much of monetary theory itself rests on the historical origins of money. Economics deals with the operation of a system. It attempts to explain the system’s stability, how the parts function together, and why dysfunctions develop. The origins of the parts may say little about their present shape or roles within the system. Modern monetary economics has been concerned above all else with explaining the value of money, and the conditions of its stability or instability. This is a problem that concerns the role of money in organizing exchange via prices. The imaginary barter economy without money but somehow still with a highly developed division of labor is a counterfactual, a tool of abstraction, which in fact the textbooks are often careful not to describe as actual history.

As for arguments that money is essentially about debt, or essentially a creature of the state: this is to make the mistake of reducing something involved in a complicated set of relationships to one or two of its moments. Economics has generally met the challenges of credit and state theories of money not with fear or incomprehension, but with indifference: if credit or the state is the answer to the riddle of money, the wrong question may have been posed.

Joseph Schumpeter captures the basic reason for chartalism’s unpopularity in his discussion of the “tempest in a teacup” surrounding the original reception of Knapp’s famous book:

Had Knapp merely asserted that the state may declare an object or warrant or token (bearing a sign) to be lawful money and that a proclamation to this effect that a certain pay-token or ticket will be accepted in discharge of taxes must go a long way toward imparting some value to that pay-token or ticket, he would have asserted a truth but a platitudinous one. Had he asserted that such action of the state will determine the value of that pay-token or ticket, he would have asserted an interesting but false proposition. [History of Economic Analysis, 1954]

In other words, chartalism is either obvious and right or interesting and wrong. Modern states are clearly crucial to the reproduction of money and the system in which it circulates. But their power over money is quite limited — and Schumpeter puts his finger exactly on the point where the limits are clearest: in determining the value of money.

The mint can print any numbers on its bills and coins, but cannot decide what those numbers refer to. That is determined by countless price-setting decisions by mainly private firms, reacting strategically to the structure of costs and demand they face, in competition with other firms. Graeber interprets Aristotle as saying that all money is merely “a social convention,” like “worthless bronze coins that we agree to treat as if they were worth a certain amount.” Money is, of course, a social phenomenon. What else would it be? But to call its value a social convention seems to misrepresent the processes by which this value is established in an economy like ours — not by general agreement or political will, but as the outcome of countless interlocking strategies in a vast, decentralized, competitive system.

Keynes understood this, and it is why, as Graeber complains, he “ultimately decided that the origins of money were not particularly important.” After a few pages at the outset of the Treatise, Keynes moved on from chartalist theory, hardly to mention it again. The bulk of the remaining 750 pages is devoted to explaining the determination of the value of money, with respect both to commodities and to other currencies, and to problems of state management of the value of money.

Where does this leave Graeber’s other alternative approach, the credit theories of money? In asserting that debt is the essence of money, Graeber seems to be saying two quite different things. First, there is the argument we have already seen that money is not a thing but an abstract unit of measurement. Now, on the economists’ list of money’s functions, “unit of account” is an absolutely standard item, alongside “store of value” and “means of payment” or “medium of exchange” (views differ as to whether these are one function or two).

Few would deny that money is, among other things, a unit of measurement. But Graeber apparently means more than this — that this is money’s essence.

As with state theories of money, this is to reduce money to one of its aspects. Problems become clear as soon as we start to think about how money does its measuring. It is odd that Graeber claims that “you can no more touch a dollar or a deutschmark than you can touch an hour or a cubic centimeter” — because there actually are things called dollars you can touch, carry around in your wallet, and spend.

And they are not measuring instruments like rulers or clocks that we take out to measure the value of something that would exist without them. Without actually-circulating money, there would be no value to measure, because the price system only emerges out of innumerable strategic price-setting decisions, each aiming to attract actual purchases: money changing hands. What circulates in this way need not be a physical thing, but it is a thing in the sense that it cannot be in two places at once: when a payment is made, a quantity is deleted from one account and added to another. That the thing that is accepted in payment may be a third party’s liability does not change this fundamental point.

The second thing Graeber seems to mean by saying that debt is the essence of monetary relations is that exchange often is, and has been, mediated by credit relations rather than through the actual circulation of money. This is undeniably true: credit relationships transform exchange so that payments do not coincide with transactions and reciprocal relationships may mean that some debts balance without ever needing to be cleared by monetary payment. Debt instruments may circulate as means-of-payment even among people not party to the original debt — and in fact most of our modern money is of this kind: we pay each other with bank liabilities.

But however far credit may stretch money, it still depends on a monetary base: people ultimately expect to get paid in some form or other. There are times in Debt when Graeber implies otherwise. He portrays credit in early modern rural England, for example, as a system of mutual aid — debt is all about trust, after all — ultimately undermined by the incursions of cold hard cash, the nexus of suspicious, calculating relationships among strangers. He takes this duality between debt and cash quite literally, to the extent that he seems to see credit relationships as a kind of charity. He claims that Adam Smith’s line about not expecting our dinner from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker “simply wasn’t true” because “most English shopkeepers were still carrying out the main part of their business on credit, which meant that customers appealed to their benevolence all the time.”

Graeber’s general reading of Smith’s worldview is quite tendentious: Smith was blind to the flourishing credit economy of mutual aid all around him, had hang-ups about debt, and “created the vision of an imaginary world almost entirely free of debt and credit, and therefore, free of guilt and sin.” The gold standard was a strategy by the powerful to undermine the informal rustic credit economy. He portrays Smith as an arch-metallist, morally opposed to debt and blind to his society’s mutual bonds of credit. In fact, Smith wrote glowingly in The Wealth of Nations about Scotland’s laissez faire approach to letting private banks issue paper money: “though the circulating gold and silver of Scotland have suffered so great a diminution during this period, its real riches and prosperity do not appear to have suffered any.”

Smith’s treatment of the relationship between bank credit-money and the precious metals is far too complex to fit into Graeber’s framework. The same can be said for the whole tradition of classical monetary theory, which was building steam at exactly the point where Graeber’s history of it breaks off, the turn of the nineteenth century. The Bank of England’s suspension of gold convertibility in 1797 and the ensuing inflation, or “high price of bullion,” sparked a theoretical and political controversy which continued sporadically across much of the century: first the so-called Bullionist Controversy, and later, the battle between the Currency and Banking Schools.

These did indeed revolve around the relationships between the value of gold, the value of national currencies, and the value of central and private banknotes. But they are not resolvable at all into Graeber’s moralistic framework. They were not ultimately questions about the “true nature of money,” but about how a system operated and the limits and potentials of state and central bank action within that system.

It was not necessarily because people were under illusions about the timeless intrinsic money-ness of metals that the gold standard lasted so long, but because it actually took a very long time for the state to build up trust in the value of its money, in circumstances where it was easy for individuals to engage in arbitrage between different forms of money, bullion and different national currencies. This trust was threatened by every inflation and banking crisis. The mint could print money, but it couldn’t print the price lists. Banks could exchange deposits for merchants’ bills of exchange, but their ability to convert deposits into central banknotes or gold depended on the state of the network of monetary flows and their position within it.

The value of gold acted as an anchor for the value of any currency convertible into it. This was not due to any inherent goldness to money, and people didn’t have to believe in any such thing to support the gold standard. There was a big difference, as Schumpeter put it, between theoretical and practical metallism, a difference which does not register in Graeber’s picture.

In the modern period, state after state committed to metallic anchors as strategic decisions to enhance trust in their national currencies. Gold eventually beat out the other metals on a world scale thanks to various accidents and a snowballing network effect. The point was never to drive out state paper money, but to promote its acceptance as a stable standard of value. Neither was it intended to wipe out credit-money, but to tend and grow it by taming the wild fluctuations of bank credit.

These were problems that could not be answered with metaphysical ideas about the true nature of money. They were problems of social science.

The ultimate killer of the gold standard in the twentieth century was not changing minds about the nature of money, but the rise of the labor movement and collective bargaining: deflations became more painful and politically unacceptable. Money-wages and prices could no longer adjust so easily to shifts in the economic flux; employment no longer sacrificed on the “cross of gold.” But the further the capitalist monetary system stretched away from its anchor in the precious metals, the more states found it necessary to have other ways of sustaining confidence in the value of their currencies by targeting inflation. An anchor to one commodity was, in fits and starts, replaced by a moving, flexible anchor to a whole basket of commodities averaged together. It is no accident that the period since the formal gold tie was finally cut has seen inflation become the overriding priority of economic policy. States print the money, but not the price lists. We live in an era not of fiat money, but of what Keynes called “managed money.” Unemployment disciplines money-wages and central banks have become the queens of policy, technocratic institutions isolated from democracy, their jobs too important and technical for that.

None of that story appears in Debt. Instead, Graeber has little to say about capitalism’s Golden Age except this:

The period from roughly 1825 to 1975 is a brief but determined effort on the part of a large number of very powerful people — with the avid support of many of the least powerful — to try to turn that vision into something like reality. Coins and paper money were, finally, produced in sufficient quantities that even ordinary people could conduct their daily lives without appeal to tickets, tokens, or credit.

Any history covering 5,000 years is inevitably going to gloss over the odd century and a half. But you would think this century and a half fairly important for understanding our present situation.

And so we come to the final chapter, where Graeber cashes out what all this means for us, living near the “beginning of something yet to be determined.” Our present era begins precisely in 1971, when the US unilaterally suspended its Bretton Woods obligation to exchange gold for dollars at $35 per ounce. Disappointingly, for a period in which debt and credit take so many fascinating forms and seem so close to the center of life, Graeber chooses to focus almost entirely on a single kind of debt — US Treasury bonds — and an argument that the large and sustained national debt of the US government constitutes a kind of imperial tribute.

Out of the whole book, this argument has received the most criticism from reviewers, so I will not go over the territory again. (Henry Farrell’s at Crooked Timber is comprehensive and on target.) But both the decision to make this the focus of the conclusion, and the mode in which the argument is made, highlight again Graeber’s aversion to economic analysis. It is certainly true that the position of the US dollar in the world economy allows the American state to sustainably fund a large debt more cheaply than others. But Graeber’s understanding of the reasons for that position is entirely geopolitical.

To understand the position of the dollar requires an understanding of international macroeconomics, finance, and policy. Graeber believes that the US public debt is “a promise . . . that everyone knows will not be kept,” but the truth is exactly the opposite: Treasury bonds are considered the safest, surest, most liquid store of value in the world. The central banks of the surplus countries whose currencies are managed relative to the dollar accumulate their reserves as a byproduct of exchange rate management, and have to hold them somewhere.

It is in this chapter that Graeber’s blithe dismissal of economics — really, a willful ignorance — grates the most. Mainstream economics comes in for another lashing — but the examples of economics he cites are from Ludwig von Mises, an Austrian far from the mainstream and forty years dead, and Niall Ferguson, a conservative historian!

Monetary policy is dismissed as “endlessly arcane and . . . intentionally so”; central bank strategy after the 2008 crisis described as “yet another piece of arcane magic no one could possibly understand.” A chart — one of four in the chapter, and in the entire book — is a welcome attempt to present some quantitative data, but it compares government debt (a stock) to the military budget (an annual flow) — they happen to have a similar shape when the axes are scaled just so.

An attack on economics evidently goes down well with Graeber’s target audience. It is not a hard sell to anger the average leftist about the power and arrogance of the discipline, or to flatter them that they can see through it all. But it is an unfortunate attitude. “For — though no one will believe it,” as Keynes once wrote, “economics is a technical and difficult subject.”

Modern society has a complex, impersonal structure by which goods and services are produced and distributed. Explaining this structure is economics’ primary problem. The neoclassical strategy for solving it through methodological individualism led to the unrealistic assumptions Graeber derides. He is perfectly right to reject that solution. But it still leaves the problem, which will not be solved just by thinking in terms of a wider range of human motivations. There is an economics-sized gap in Graeber’s history, which he cannot fill. The answer to bad economics is good economics, not no economics. We need a genuine political economy.

Pierre Berger, a French economist responding to a previous incursion by the anthropologists, wrote in 1966: “With no disrespect to history, one is obliged to believe that an excessive concentration on research into the past can be a source of confusion in analyzing the present, at least as far as money and credit are concerned.” He meant that economics studies a system, and the origins of its parts might mislead about their present functions and dynamics.

Of course, he is quite wrong that history must confuse: it is just that we need the right kind of history, which seeks to explain the evolution of a material system. Stringing together 5,000 years of anecdotes is not enough.