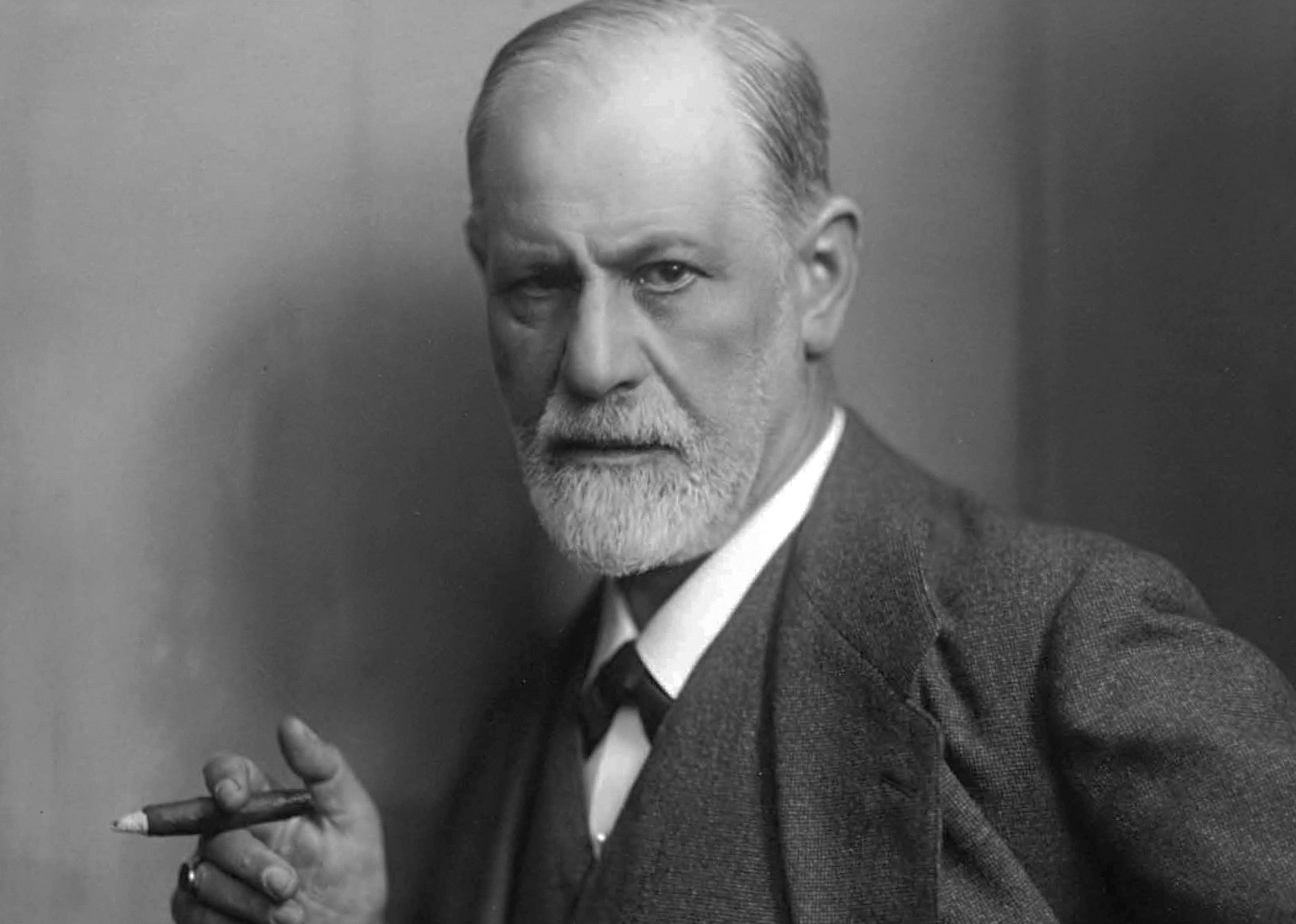

How Red Vienna Revolutionized Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud often regretted the fact that most of his patients were drawn from the upper classes. But when socialists turned Vienna “red” after World War I, neurotics both rich and poor gained access to free treatment and new experimental methods.

Sigmund Freud often regretted the fact that most of his patients were drawn from the upper classes.

In September 1918, in the dying days of the Great War, Sigmund Freud laid out a new mission for the psychoanalytic movement. Speaking to the first psychoanalytic congress since the outbreak of the war, Freud acknowledged the impediments that restricted their therapeutic work. Limited by the “necessities of our existence” to treating the “well-to-do-classes,” “at present,” psychoanalysts could “do nothing for the wider social strata, who suffer extremely seriously from neuroses.” Yet such limitations had to be overcome.

Freud argued that the neuroses were just as much a threat to the nation’s health as tuberculosis — and could equally little be left “to the impotent care of individual members of the community.” Turning his gaze to the imminent postwar situation, Freud confidently predicted that the “conscience of society will awake” to the right of the “poor man” to treatment for his mind. When it did, new institutions, staffed by analytically trained physicians, would be founded, offering treatment to the broad masses free of charge. As distant and “fantastic” as this prospect appeared amid the devastation of the war, Freud insisted that “sometime or other . . . it must come to this.”

Over the decades before World War I, analytic therapy and bourgeois privilege had gone hand in hand — crystallizing an image, indeed one that still persists today, of psychoanalysis as the preserve of the upper and upper-middle classes. In 1895, Freud remarked that his patients belonged to “an educated and literate social class,” adding a decade later that analytic therapy was ideally suited to “valuable” individuals possessing a “certain level of education and a fairly reliable character.”

Progress in technique, furthermore, did little to nourish hopes for a broader application: the more the principles of its practice were refined, the more arduous and protracted analytic therapy became. The outcome was a stance of resigned acceptance bordering on capitulation. “Poor ourselves and socially powerless, and compelled to earn our livelihood from our medical activities,” Freud wrote in 1917, “we are not even in a position to extend our efforts to people without means . . . Our therapy is too time consuming and too laborious for that to be possible.”

But at the congress just one year later, Freud sounded a radically different note — setting psychoanalysis on a path of experimental reinvention, now in the service of social justice. “[W]e have never prided ourselves on the completeness and finality of our knowledge and capacity,” he insisted; rather “[w]e are just as ready now as we were earlier . . . to learn new things and to alter our methods in any way that can improve them.” For the many younger analysts who took inspiration from these words, the central, defining challenge of interwar Freudianism would be to create a psychoanalysis for the masses. From their efforts to expand the possibilities of analytic therapy, a new psychoanalytic movement would emerge — one whose fate was intimately linked to that of social democracy.

Postwar Welfare States

Freud was far from alone in envisioning a more progressive future at the end of the war. In Central Europe, total war had pushed the combatant societies to the brink of moral and physical collapse. Society was disintegrating under the pressure, and military defeat fatally undermined the legitimacy of the established monarchies. But with the collapse of the old, there also came remarkably bold efforts to imagine and create the new.

Amid a democratic wave that would crest and break in the postwar revolutions, sweeping away the Habsburg and Hohenzollern monarchies, many experts looked to far-reaching, egalitarian forms of state intervention to restore social stability. In proposals for recovery that served as blueprints for a new social order, social democrats and their allies laid the imaginative foundations of the postwar democratic welfare states.

Freud’s personal political allegiances lay with liberalism (“I remain a liberal of the old school,” he would write in 1930). Yet his 1918 address aligned psychoanalysis with the democratizing, egalitarian spirit of the times. Both as an economic and a political program, liberalism emerged from the war profoundly discredited, its cherished values displaced by new totalizing and collectivist imaginaries. Social upheaval exacerbated the ideological crisis. As material deprivations reduced their standard of living and rampant inflation ate away at their savings, many bourgeois were gripped by what Freud’s friend and follower Sándor Ferenczi called the fear of “our imminent proletarianization.”

“All one’s energy,” Freud wrote to his disciple Karl Abraham, “is devoted to maintaining one’s economic level.” The foundations of liberal ideology crumbled away with the bases of bourgeois material security, forcing Freud to look beyond his own class to ensure the survival of his profession. The very viability of private clinical practice appeared to be in question. Like the new democratic republics in Austria and Germany, the future of psychoanalysis appeared to lie with the masses.

But total war had also created an urgent need for mass psychotherapeutic intervention. From its outbreak, the war had produced a veritable epidemic of nervous disorders in the mass conscript armies. As the specter of total (military and social) collapse grew more threatening over the last year of the war, reports began to circulate of the successful application of modified forms of psychoanalysis in the treatment of the war neuroses.

For the German psychiatrist Ernst Simmel, a simplified analytic-cathartic technique, combining hypnosis with free association, allowed him to resolve the symptoms of war neurotics in a mere handful of sessions. Invited to present his work before the 1918 psychoanalytic congress — an event sponsored and attended by keenly interested civil and military authorities — Simmel contended that his abridged and combined method might one day be implemented in what he termed the “mental clinic of the future.” With the mass application of analytic therapy in the war, a new horizon of possibility had opened up, one that spoke directly to the urgent needs of society at a moment of dissolution.

In “Red Vienna”

Six weeks after the congress, the war came to a close. The dire conditions prompted Freud to bitterly (and ironically) lament to Ferenczi that “[n]o sooner does [psychoanalysis] begin to interest the world on account of the war neuroses than the war ends.” In fact, however, psychoanalysis was poised to experience a profound expansion, a dramatic rebirth, as a younger generation streamed into its ranks in the wake of the war.

For these new converts, historian Elizabeth Ann Danto writes, psychoanalysis was a “challenge to conventional political codes, a social mission more than a medical discipline.” While the more radical members of this new generation saw in psychoanalysis a program for emancipation from bourgeois convention, their radical aspirations — as Danto and historian Eli Zaretsky have shown —were set against the backdrop of a broad social democratic consensus that united the profession. Regardless of their prior political affiliations and identifications, all psychoanalysts shared a deep commitment to the social mission that Freud outlined in September 1918.

The socially progressive spirit of psychoanalysis in the wake of the war was captured in two remarkable educational experiments that were founded in the environs of Vienna in 1919. In the first of these — a children’s home for several hundred Jewish refugee war orphans organized by the young socialist Siegfried Bernfeld — psychoanalysis was embraced as an indispensable foundation for the “new education” that he and his fellow teachers sought to realize. “Had we not found a guide in the Freudian theory of the drives we would have remained totally in the dark,” he wrote. Animated by an anti-bourgeois collectivism, the educational aspirations of the children’s home contrasted markedly with the other postwar experiment in “mass pedagogy” run by August Aichhorn, a municipal educator who, like Bernfeld, entered psychoanalytic training in the wake of the war.

Aichhorn’s educational welfare institute for delinquent youth reflected his more traditional political sensibility, which aspired not to transcend but rather to restore the nuclear family. Yet like Bernfeld’s experiment, Aichhorn’s breathed the progressive spirit of the new era, both in its anti-authoritarian ethos and in its commitment to social welfare. Describing the psycho-pedagogical assistance provided by his state-funded institute, Aichhorn contended that if earlier, such support “originated in a charitable sensibility and was a voluntary act,” today it was “a duty, a recognition of the right that the individual has from society.” Far from being defined against the state, the rights of the individual, for Aichhorn, were inseparable from a greater degree of state intervention.

The postwar moment was a social democratic one, and the psychoanalytic movement was carried along in the progressive stream of the times. Nowhere was the power of this current more evident in postwar Central Europe than in Vienna, where the Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP) assumed control of municipal politics from the conservative, antisemitic Christian Social Party, from 1920 the dominant force in national politics.

Red Vienna, as it came to be known, was the centerpiece of a political strategy that aimed at the peaceful overcoming of capitalism through democratic struggle and the cultural elevation of the masses. Designed as an anticipation of the future socialist utopia, the Social Democratic municipality was an achievement at once material and ideological. In its massive rent-controlled apartment complexes (“People Palaces”), its network of low-cost health and counselling clinics, and its countless progressive educational initiatives, Red Vienna combined concrete improvements in the lives of working people with the aim of producing a new socialized and solidary humanity.

Proximity to this social democratic political culture would have a remarkably galvanizing effect on the psychoanalytic movement, helping to inspire what the analyst Helene Deutsch termed the “revolutionism” of the second generation. Yet for some Freudians, Berlin provided a more congenial setting for combining psychoanalysis with radical politics. For the socialist analyst Otto Fenichel, who emigrated from Vienna to Berlin in 1920, younger analysts were “naughty children” defying the strictures of their more conservative older colleagues. Distance from Freud and the old guard in Vienna, his friend Wilhelm Reich wrote, provided an atmosphere in which more rebellious analysts felt they could “breathe more freely.”

An even greater draw, however, was the establishment in Berlin of the first formalized psychoanalytic training program, offering what historian George Makari calls “the most rigorous and structured education in psychoanalysis in the world.” The Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute was founded in 1920. The centerpiece of both the social outreach and training program of the new institute was the first psychoanalytic outpatient clinic to offer free or low-cost treatment to the underprivileged.

The Berlin Polyclinic was the first, but other societies were quick to follow suit. Between the wars, writer Christopher Turner recounts, at least a dozen similar clinics would be founded across the international psychoanalytic movement. In 1922, with the assistance of the SDAP, Vienna opened its own — the Vienna Ambulatorium. “Eventually,” Danto writes, “all analysts treated gratis at least one fifth of their practice, an unspoken custom shared by even the most accomplished doctors in Vienna.”

Immensely popular among the broader public, the new clinics adopted a more functionalist approach to treatment — one evident, Danto notes, in the striking contrast between the unadorned simplicity of the Polyclinic consulting rooms, designed by Freud’s architect son Ernst, and the luxuriant ornamentalism of Freud’s office at Berggasse 19. “A chic but modest outpost for a military-style campaign against nervous disorder,” in Turner’s words, the Polyclinic privileged practical expertise and technical efficiency in the restoration of mental well-being.

Beyond Liberal Practice

As innovative and ambitious as they were, the new outpatient clinics struggled to come to grips with the influx (“we were at a loss how to deal with it,” Reich recalled). Despite these limitations, which left Reich convinced of the futility of treating collective problems through individual therapy, the struggle to develop a “therapy for the masses” would give rise to a new psychoanalysis between the wars.

Reich’s own work with indigent patients at the Vienna Ambulatorium is one of the most striking testaments to this transformation. Working with severe — borderline psychotic — cases, Reich would make a distinction between the “‘good bourgeois’ symptoms” of Freud’s prewar case studies of repressed hysterics and obsessional neurotics and the more profound disorders of the “impulsive characters” he treated. In contrast to the “circumscribed” symptoms of bourgeois neurotics, Reich’s lower-class “character neurotics” were overwhelmed by their disorders.

Echoing Aichhorn, Reich insisted that the fundamental cause of the characterological disorders he faced was the greater childhood exposure of his patients to material misery and to a brutal social milieu. With the emphasis shifted onto the environment, neuroses assumed a new guise. Having previously been regarded as expressions of unique individuality, grounded in the personal life history of the patient, they increasingly came to figure in psychoanalytic thought as impersonal reflections of broader social and political pathologies.

Simmel’s work with war neurotics signaled the emergence of this new perspective. But as more analysts looked beyond the sheltered confines of the bourgeois family sphere — indeed, as this sphere began to crumble — the etiological importance of environmental forces came to figure more prominently in psychoanalytic thought. (The contemporary emergence of psychoanalytic social theory attests to the same attempt to come to grips with a volatile, threatening society.) The scope of psychoanalysis was widening — and new subjects and types of suffering increasingly were crowding out the earlier norm of the adult, bourgeois (hysterical or obsessive) neurotic. The free clinics were one important site for this redefinition and rethinking, but at a time of professional expansion and diversification, they were far from the only one.

Anna Freud’s therapeutic and educational work with children was one such site. A close collaborator with Aichhorn and Bernfeld, Anna Freud would develop a distinctive approach to the treatment of children’s disorders from the mid-1920s onward. Against the more conservative school of child psychoanalysis that flourished in London around the figure of Melanie Klein, Freud and her followers insisted on the importance of social factors in both the clinical understanding and treatment of children’s neuroses.

Inspired by the educational and welfare reforms of Red Vienna, which strove to establish more rational and empathic regimes of childcare and primary instruction, Anna Freud insisted that the child’s environment was the solution as well as the cause of its suffering. “We lighten the child’s task of adaptation,” she wrote, “as we endeavor to adjust his surroundings to him.” As Anna Freud’s experimental work with children indicated — together with the technical innovations of Reich, Ferenczi, Aichhorn, and Simmel (the latter the director of a short-lived in-patient clinic for severe cases) — the therapeutic politics of psychoanalysis were very much in flux.

Designed for an independent bourgeois subject, classical analytic therapy had been a liberal practice, one that limited the authority of the analyst in order to preserve the autonomy and individuality of the patient. Yet it was liberal also in the exclusions it imposed. Intended only for patients possessing a degree of personal independence, cultural literacy, and material security, those whose disorders reached deeper and who lacked the resources of the privileged fell, with scant few exceptions, entirely outside its purview.

The interwar, however, saw a number of ambitious attempts to break out of the constrictive limits imposed on analytic therapy by its liberal principles. In his 1918 address, Freud had speculated that (for reasons of efficiency) the “pure gold of analysis” might have to be supplemented by the “copper of direct suggestion” and even by hypnotic influence in the new free clinics. Though Freud quickly thereafter retreated to analytic orthopraxy (“I will probably continue making ‘classical’ analyses,” he told a disappointed Ferenczi), other analysts pushed forward. While the imperative of reaching the wider social strata impelled Freudians to experiment with developing more efficient methods, the different orders of suffering and types of subjects they encountered likewise demanded a rethinking of the means and ends of analytic therapy.

“[I]f an adult neurotic came to your consulting room to ask for treatment,” Anna Freud wrote in 1927, “and on closer examination proved as impulsive, as undeveloped intellectually, and as deeply dependent on his environment as are my child patients, you would probably say, ‘Freudian analysis is a fine method, but it is not designed for such people.’” Devised (like the reforms of Red Vienna) for a more vulnerable, dependent subject than classical liberal analysis, the new techniques developed by revisionists offered patients a greater degree of emotional support and pedagogical guidance.

Yet they were also, in many cases, overtly normative and disciplinary, geared toward realigning deviant subjects with social norms (often through the re-construction of a socially adapted superego on the model of analyst’s own). Classical psychoanalysis, by contrast, aimed only to enable the patient to choose how to resolve underlying conflicts by bringing the contending forces into consciousness. The post-classical methods devised by interwar reformers, however, aimed to safeguard both the fragile ego from a pathogenic social environment and society from the dangerous forces in the psyche.

As critical voices would point out, there was a danger in this — the danger that (forgetting the lessons of the unconscious) psychoanalysis could degenerate into a pedagogical method for adapting individuals to society. Yet in marked contrast to its Kleinian and Lacanian critics, the progressive Central European psychoanalysis that pushed beyond the limits of liberal analytic practice was equally committed to altering the social environment to suit the needs of the individual.

In its dual aspect, it reflected the paradoxes of the social democratic political culture that emerged in Red Vienna, where nurturing support for the victims of social violence was joined to benevolent paternalism. At a deeper level, the contemporary revisions of psychoanalysis internalized the post-liberal social contract of the Social Democratic welfare state, a contract in which the expanded rights of the individual were grounded in the expanded power of the state over society.

Opening Toward Liberty

Psychoanalysis lurched to the Left in the wake of the war, but Freudians were not always met with a welcoming embrace in Red Vienna. While a handful of “promising” links, in Anna Freud’s recollections, developed between the socialist municipality and the psychoanalytic movement, they remained just that — “promising.” The socialist leaders of Red Vienna were torn between viewing psychoanalysis as a valuable resource in their struggle to create a better life for the masses and a political liability on account of its unsettling emphasis on sexuality. (Freud’s own famous cultural pessimism also reinforced the skepticism of many socialists.) When staffing the institutions of the Red Vienna, Social Democrats generally opted for Adlerian individual psychologists — purveyors of a stubbornly optimistic, one-dimensional psychology of social conformity — over their rivals, the Freudians. What social democracy failed to provide in material support, however, it more than made up for in the realm of spirit.

With the destruction of democracy in Germany and Austria — and the banning of the Social Democratic parties by Nazism and Austrofascism in the early 1930s — the progressive culture of interwar psychoanalysis also faded. The fact that it was done in by the irrationality of a society that it purported to treat was profoundly chastening and disillusioning. By the onset of the Cold War, a more cautious, conservative psychoanalysis would dominate the International Psychoanalytical Association.

Yet the struggle to create a psychoanalysis for the masses was an experiment with valuable lessons for the present. Nourished by social democracy, psychoanalysts began to think of their practical, therapeutic work beyond the limitations of liberalism. To frame the matter somewhat differently, they began to see in socialism the only possibility for the realization of the personal rights and individual liberty that liberalism at once championed and foreclosed.

It was in the new free clinics, Simmel wrote, that the person without means first enjoyed the “right and possibility to bear the depth of their unconscious mental life in unburdening free conversation.” An impossible demand even within the progressive horizon of the interwar period, “the right of the poor man” to treatment for his mind was nonetheless a portal to imagining a better future.