The Rise of Community Control

The New York Board of Education and teachers unions' refusal to fight racism in public education was responsible for the 1968 Ocean Hill-Brownsville crisis, not Black Power.

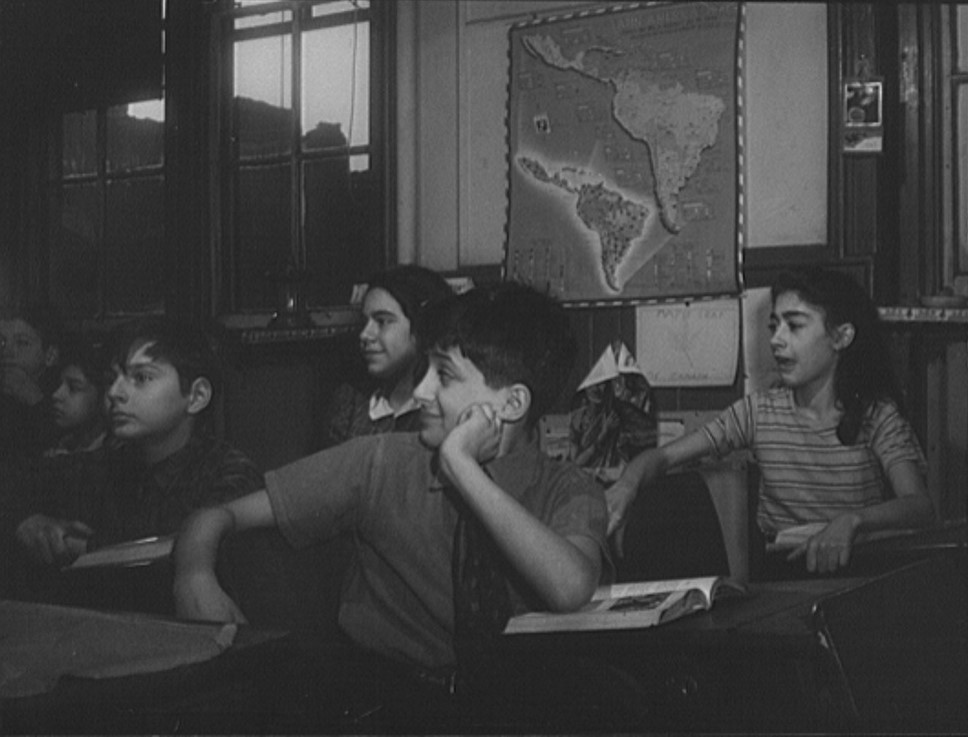

Reading class in Public School Eight on King Street, New York, NY, January 1943. Library of Congress

A great deal has been written over the last fifty years about the 1968 New York teachers’ strike. A major argument among some who have examined this episode is that such conflict was rooted in the politics of the 1960s.

Writer Jonathan Kaufman maintained that conditions had changed for blacks and Jews in the 1960s. “Jews were unhappy with the rising militancy and anti-white sentiment emanating from the more militant parts of the civil rights movement. According to Kaufman, the “rising black militancy was demanding power, real power.” Kaufman maintained that black militants, such as Rhody McCoy, head of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school district, community leader and Black Power advocate Sonny Carson, and Les Campbell of the Afro-American Teachers’ Association, an “openly anti-Semitic” organization, were at the root of the problem in Ocean Hill-Brownsville.

Historian Joshua Zeitz argues that New York City black activists missed the mark. Instead of addressing those who were responsible for neighborhood segregation such as those in banking and real estate, parent and community activists turned on teachers. “As grassroots activists began gathering momentum for a community control scheme, they grew increasingly casual in their use of such terms as ‘educational genocide’ and intellectual ‘colonialism,’ reflecting a growing consensus among movement leaders that their cause was at one with anti-colonial struggles in the ‘third world.’ Such vitriolic attacks on a predominantly Jewish teaching force were bound to result in a conflagration, as indeed it did.”

Richard Kahlenberg, the author of a biography on Al Shanker, argues that civil rights groups and labor unions forged a powerful coalition nationally and in New York City. But almost immediately in 1966, the coalition began to splinter as core values like nondiscrimination and the importance of labor were discarded.” It was the “liberal betrayal,” and Black Power that turned their backs on core liberal principles such as racial integration, merit-based hiring, labor unions’ right to organize, and labor’s right to due process.

The problem with the thesis that Black Power was responsible for the crisis in Ocean Hill-Brownsville is it ignores an earlier history of conflict between teachers and black and Latino activists and parents.

Those critics of community control fail to see that those operating the school system had reduced black and Latino parents to observers while giving a professional class, most of whom had no close relationship with the communities they served, complete power to determine their children’s education. Although relegated to the sidelines, parents were not passive. Years before the community control movement, parents and activists carried out campaigns attempting to assure that their children received a decent education. They met resistance from board officials and at times from teachers, convincing many that those who ran the schools had no interest in educating black and brown students.

Long before 1968, the Board of Education, the Teachers Guild, and later, the United Federation of Teachers were the cause of the 1968 confrontation with black and Latino communities in the city.

Roots of the Community-Control Movement

The effort for community control of schools has its roots in the school integration campaign. While civil rights campaigns in the South in the 1950s and 1960s have received a great deal of attention, one of the largest civil rights struggles took place in New York City over the issue of school segregation in those same years.

In the fall of 1955, the Parent Education Association (PEA), an organization created in the late nineteenth century to improve the public school system, released a report detailing widespread segregation in the school system, including forty-two de facto segregated elementary schools (a student body that was 90 percent or more black and Puerto Rican) and nine junior high schools (85 percent or more) in the city. Despite the PEA’s findings and the New York City Board of Education’s promise to make changes, the school system did not take steps that satisfied New York City’s civil rights community.

Shortly after the PEA’s report, the Board of Education created a Commission on Integration to study the problem of segregation in the public school system and make recommendations to fix the problem. The commission created a number of subcommittees to study various areas of school segregation. In 1957, the subcommittee on personnel recommended that — to help provide equal services to ghetto schools that were short of professional staff and to assure that they would not be assigned the least experienced teachers — the board transfer experienced teachers to predominantly black and Latino schools on an involuntary basis.

In response, the New York Teachers Guild, the organization that would become the United Federation of Teachers, campaigned against the policy recommendation. In an article entitled “Integration Yes! Forced Rotation No!” Charles Cogen, president of the Guild, justified the organization’s position on involuntary transfers by claiming such a plan would lead to a “transient teaching staff,” lowering quality of education and antagonizing the professional staff whose good will was essential for the implementing integration.

Cogen argued that “difficult schools” were not a “racial problem.” The children required more remedial and guidance services, not because of inadequate resources to black and Latino neighborhoods, but because of “complex socio-economic causes….” In the Herald Tribune, Cogen argued that dysfunctional families were at the heart of children’s failures. Put simply, Cogen accused the children of not wanting to learn. “These children are more frequently impelled to take out their insecurities and frustrations on society and on the school environment.” He went as far as to infer that black and Latino children were out of control. “Their behavior, varying from child to child, run the gamut from annoyances to serious crimes.” In classrooms, black and Latino children refuse to “stay in their seats, using obscene language toward the teacher and fellow pupils, ringing false fire alarms and in general refusing to obey the necessary rules and regulations of a school situation. Criminal behavior includes assaults, robbery, extortion, destruction of property, starting fires and other types of action which bear some similarity to the Blackboard jungle.”

Civil rights and civic groups attacked the Guild’s position. Edward Lewis, executive director of the Urban League of Greater New York expressed “shock.” The Intergroup Committee on New York City Public Schools, which represented twenty-six organizations, publicly denounced the Guild’s opposition to the transfer plan. Lester Granger, president of the National Urban League, speaking to 400 people attending a conference of the United Neighborhood Houses, claimed that New York City teachers were involved in an organized campaign to avoid serving black and Latino children.

Paul B. Zuber, a civil rights lawyer who fought for school integration in New York, wrote to Rose Russell in late March, telling her he would warn Cogen and the leadership of the Guild that if they did not change their position, he would go before the Board of Estimate and oppose pay raises for teachers. He noted that seventy-five parents, ministers, and leaders had agreed to speak before the Board of Estimate opposing the teacher pay hike. He and others were “tired of hearing the phony reasons teachers give as to why they don’t want to teach in Harlem.”

Zuber’s letter clearly pointed to the deep divide between the Harlem community and the Guild. “If the teachers want tax money, teach our children,” to take strong measures to integrate public schools in the city, civil rights leaders, and organizations

Although the leadership of the Guild was reluctant to support strong measures to integrate the school system, civil rights activists and organizations launched a fierce campaign to end racial segregation of schools. In 1960, the Reverend Milton A. Galamison, pastor of Siloam Presbyterian Church and former president of the Brooklyn branch of the NAACP, created the Parents Workshop for Equality in New York City Schools, an organization made up of parents who fought for school integration. The Parents Workshop challenged the Board’s defense that housing discrimination was responsible for school segregation. The group maintained the even when black and white children lived in close proximity the Board zoned black student to racially segregated schools.

Due to the Board’s intransigence, civil rights groups, including all the city chapters of the NAACP, the Urban League of Greater New York, branches of the CORE, the Parents Workshop and other grassroots organizations in the summer of 1963 formed the New York Citywide Committee for Integrated Schools to plan strategies to force the board to act on school integration.

The Coordinated Committee selected Galamison as its president and planned a one-day boycott to force the board to come up with a plan and timetable for integration. Although boycott leaders met with the UFT asking for its support of the action, the UFT refused, disappointing many in the movement. On February 3, 1964, one of the largest civil rights demonstrations in the nation’s history took place when close to 500,000 students stayed out of the New York City public schools in order to force the Board to come up with a plan and timetable to integrate the schools.

Despite the success of the boycott, the coalition that made up the Coordinated Committee soon fell apart. A few days after the boycott, all of the branches of the New York City NAACP, the Urban League, and most of the branches of CORE pulled out of the organization, accusing Galamison of acting in an arbitrary and undemocratic manner after he publicly announced that he was planning a second boycott. Just as important, the boycott did not persuade the Board of Education to respond to the demands of the protesters. Although there were calls for additional boycotts, by 1965 the school integration campaign in New York was over.

Community Control

The struggle for community control was, in large part, a response to the failure on the part of those who operated the schools to make any substantive changes assuring an adequate education to black and brown children. By 1965, parents and community activists argued that if the Board of Education was not going to assure an adequate education to their children then black and Latino parents should control the schools in their communities.

In December 1966, after a number of community school activists led a sit-in at the Board of Education demanding that black and Latino parents have more say over their children’s education, they formed the People’s Board of Education and occupied the board for three days. The People’s Board demanded that parents have a say in the day to day operation of the schools their children attended and that the Board of Education be responsible to parents. Among its other demands was that the Board recruit people from the community and appoint them as assistant teachers (para-professionals). The People’s Board of Education was just one of several grassroots groups calling for community control.

Aware of the growing demand for community control, Mayor John Lindsay, a liberal Republican, with the financial support of the Ford Foundation, set up three experimental school districts, one in Harlem, one in lower Manhattan, and the third one in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Brooklyn. The three experimental school districts could make decisions about curriculum and budget. It could select its unit head (superintendent) and approve the unit head’s recommendation for school principals. But there was no provision for firing teachers.

In the spring of 1968, the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school district removed thirteen teachers who were accused by the governing board of sabotaging the experiment. McCoy suggested to the teachers that they should seek transfers out of the district. Albert Shanker, the president of the United Federation of Teachers, the union that represented all New York City public school teachers, threatened to call a strike if the teachers who were removed were not reinstated.

When the school district refused to allow the teachers back into the schools on September 9, 1968, the UFT called a strike, shutting down the entire school system. Although the UFT agreed to end the strike on September 11, after the Board called for the teachers to be reinstated, on September 13 Shanker called a second strike when the local school board refused to allow the teachers back into the schools. Although another agreement had been reached by the end of September to end the strike and McCoy and seven of the eight principals in the district had been relieved of their duties by the superintendent, the UFT launched a third strike on October 14, claiming that one of the junior high schools should be closed because it was unsafe for teachers.

On November 17, the Board of Education reached an agreement with the UFT, ending the school crisis. The agreement allowed all the teachers in the district to return to their schools and initiated the appointment of an associate state commissioner to serve as a trustee of the district. It called for the creation of a special state committee to see that the rights of teachers were protected. In 1969, the state passed a decentralization bill creating thirty-three school districts. The bill also created a new board of education with seven members. However, parents were not provided power to decide on the employment of school professional staff or other vital powers that would provide them with real community control.

Community control, like the school integration movement, was an attempt to redefine the relationship that parents had with a school system which had marginalized black and Latino parents. Parents wanted to have decision-making power when it came to educating their children. The 1968 New York City strike was just one episode in a long history between black and Latino parents and a school system that prioritized protecting the interests of those who ran the system instead of properly educating black and brown children.