Pac’s Passion

The new Tupac biopic All Eyez on Me does an injustice to the politics and contradictions that drove him.

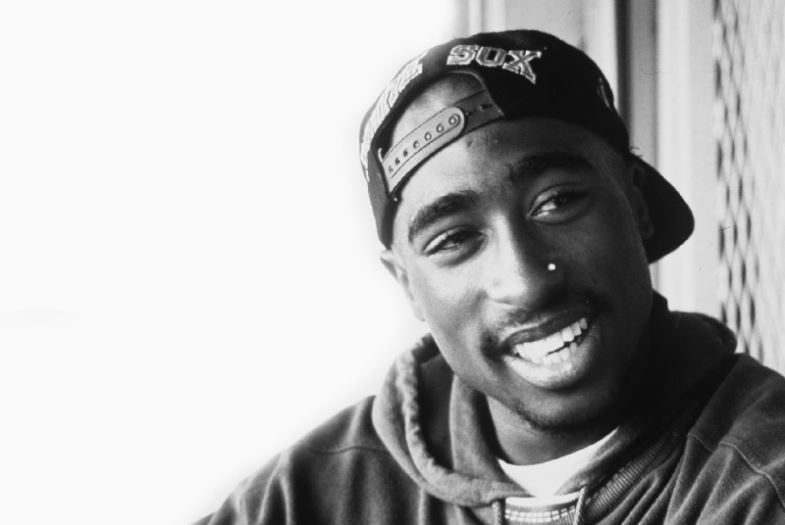

Tupac Shakur in 1993.

June 16 was Tupac Shakur’s birthday. It was also the day the rap icon’s new biopic, All Eyez on Me, debuted in theaters across the country. I went to go see the film opening night. The theater was packed and there were hardly any white people at the show. The excitement in the room was palpable. But Tupac never showed up.

His portrayal in the film was lifeless, though actor Demetrius Shipp Jr. played Tupac admirably. Much of the narrative felt like a series of disconnected vignettes drained of continuity and heart. But each time a Tupac song played, the audience roared along, reciting the lyrics with such force that it was as if Tupac lived anew with each syllable.

Tupac’s message still resonates.

June 16 is also the date Philando Castile’s killer, Officer Jeronimo Yanez, was found not guilty of manslaughter. It was a decision as predictable as it was cruel. Who can forget the video? Castile sprawled across the passenger’s seat, his girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, recording. Diamond’s toddler daughter sits in the back. Yanez had just fired seven rounds into the car. Philando bleeds to death as Diamond narrates.

Diamond is so calm, talking patiently with the cop that just killed her boyfriend. She’s powerless. We too, the digital onlookers, watch the video in a state of helplessness. The cop’s depravity appears insurmountable, and resignation feels so inevitable. Tupac Shakur speaks to us in these moments.

Cops on my tail, so I bail ’til I dodge ’em / They finally pull me over and I laugh / “Remember Rodney King?” and I blast on his punk ass.

These are the lyrics to 1991’s “Soulja’s Story,” a narrative based on the lives of black prisoner and revolutionary George Jackson and his younger brother, Jonathan, who died attempting to free him. Like so many of us, Tupac had seen a video of a black man brutalized — Rodney King. But he aspired to more than mere spectatorship. Where resignation to fatalism tempts us, Tupac screams rebellion, against the police, against injustice, against all that would destroy us. Tupac’s words speak life to those in struggle. And he lived them.

October 31, 1993, two years after the Rodney King beating. Tupac is in Atlanta, riding in a car when he sees two white men assaulting a black man. He’s an actor and budding rap star with everything to lose, yet Pac intervenes. They are cops. They pull their weapons. Tupac retrieves his gun. He crouches on one knee, focused and perfectly calm. He fires multiple rounds. At least one officer is hit.

Earlier in ‘93 he had released his second album, Strictly for My N.I.G.G.A.Z., which included career-defining hits like “Keep Ya Head Up” and “I Get Around.” His second film, Poetic Justice, debuted in July. Tupac had fame and wealth. He was comfortable. He still shot two cops, confirmed racists who had stolen guns from the police evidence room. The two plainclothes officers were drunk at the time of the incident. Pac beat the case and all charges were dismissed. What motivated him to rebel? The new film All Eyez on Me fails to answer this question, even as it depicts the shooting.

In the film, politics exists merely as footnote, a sequence of platitudes. “Black is beautiful,” Mutulu Shakur exclaims in a basement meeting of a black radical organization. Reduced to mild sloganeering, it’s difficult to fully feel the scenes in which the US government is hellbent on harassing and imprisoning Tupac’s parents, Mutulu and Afeni. In reality, Tupac’s family was much more than bland gestures and shallow words. His stepfather Mutulu is famed political exile Assata Shakur’s brother. In 1979, when Tupac was eight, it was Mutulu who broke Assata out of prison following her conviction for killing a state trooper. This event is not even referenced in the film. The revolutionary character of Pac’s kinfolk is defanged, leaving a gaping hole in the narrative. As a result, revolution is drained of its fervor, only spoken of fleetingly in Afeni’s decontextualized lectures at Tupac.

Because the film doesn’t provide the revolutionary content of his background, it cannot understand Tupac’s feelings. Tupac is largely a passenger in his own narrative. Events happen to and around him, leaving his inner life largely unexplored. “A true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love,” Che Guevara once said. But what happens when a revolutionary love goes so often unrequited?

Tupac loved his revolutionary stepfather Mutulu, only to see him imprisoned. Tupac loved his Black Panther mother Afeni, but watched her succumb to crack addiction. As a teenager in Baltimore, he channeled his passion into politics and art. He joined the youth wing of the Communist Party. He was also starring in plays at Baltimore School for the Arts. Just as he found his stride, Pac was abruptly shuffled off across the country to Oakland. He had to feel a profound sense of loneliness, of anger.

The depth of Tupac’s suffering is largely ignored in the film. To feel so deeply, to yearn for love — a truly transformative love that ruptures injustice and inspires insurrection — while living a life of persecution and alienation, must have been a maddening dissonance. At the time of his death, Tupac’s stepfather Mutulu wrote a letter from prison to Vibe Magazine titled “To My Son.” “The pain inflicted that scarred your soul but not your spirit gave force to rebellion. Many couldn’t see your dreams or understand your nightmares,” Mutulu writes. It’s clear the film doesn’t see or understand Tupac either — in large part because it refuses to take politics seriously.

The film narrates most of Tupac’s life through flashback as Pac meets with a reporter for an interview while in prison. It is not until notorious Death Row Records executive Suge Knight bails him out that the story moves forward. It’s as if all of Tupac’s life, the experiences that made him so relentlessly passionate and political, were a mere formality leading up to his escapades as a Death Row playboy. There’s no continuity between the politics structuring his childhood and the artist and man he became.

Tupac began his career beefing with the US government, even getting into a shootout with the police, only to be reduced to fixating on a petty industry feud with Notorious B.I.G. and Bad Boy Records. This marked decline mirrors the retreat of revolutionary politics globally. Tupac lived in a time of great demobilization, as revolutionary movements had been exhausted globally.

The fall of the Soviet Union ushered in what Francis Fukuyama infamously called the “end of history.” Resistance to capitalist hegemony seemed futile. In the United States, the LA riots in response to the Rodney King beating and police acquittal, the Million Man March, and the O.J. trial all became the national touchstones of racial justice. These events were transgressive and confrontational, but they were disconnected from any broader paradigmatic challenge to the status quo. Whatever Tupac’s political commitments, he was in an era where channeling those impulses in a radical direction was unlikely. His evolution from the spirit of 2Pacalypse Now to his later Death Row material happened in this context.

The film speaks of Tupac’s contradictions, but it cannot grasp them. In one scene, the interviewer asks an imprisoned Pac about how he can talk about building up black communities, but then release the party anthem “I Get Around.” Tupac dismisses the question, but the film feels stuck in a similarly shallow space. In fact, Pac’s imprisonment was a contradiction itself. At the very least it showed he did not always live up to his words.

Tupac was a man who wrote “I think it’s time to kill for our women, time to heal our women,” but was later convicted of first-degree sex abuse. Though he proclaimed his innocence, he admitted he felt “ashamed” and did not stop other men from assaulting her because he “wanted to be accepted” by those men. Rather than explore this tension, the gap between word and deed, the film portrays the incident as a spurned and malicious woman out to get Tupac. In the scene in which Pac is convicted, the woman, Briana, smirks gleefully as the guards take him away while his mother sobs.

As fiction, the film’s handling of sexual assault was offensive in its own right. The fact that it was a glorified smear against a real woman is even worse. This distortion shows the great lengths the movie goes to ensure that Tupac never has to make a meaningful choice in the narrative. Without choice and context, the audience cannot understand Tupac’s flaws, making melodrama of Tupac’s descent into paranoia. The film ignores and distorts Tupac’s politics in order to fetishize the petty feuds of his Death Row period, failing to truly capture the tragedy of a fallen revolutionary.

Tupac was characterized by both profound compassion and a lust for vengeance. Above all he was motivated by one animating force: love. “I knew your love and understood your passion,” Mutulu continues in his letter to a posthumous Tupac. Still, I imagine Pac talking to Philando Castile’s girlfriend, Diamond, who is now raising her child alone after Philando was killed.

You can’t complain you was dealt this / Hell of a hand, without a man, feelin’ helpless . . . And it’s crazy, it seems it’ll never let up / But please, you got to keep ya head up

Tupac speaks to us because he felt us, he loved us. But a revolutionary love unfulfilled, a radical dream deferred, left him wounded with a pain few of us understand. He rebelled, against the world and perhaps most intensely against himself. Tupac’s contradictions contained multitudes that the All Eyez on Me movie couldn’t see.