When Frederick Douglass Met John Brown

What role did Frederick Douglass play in John Brown's Harpers Ferry raid?

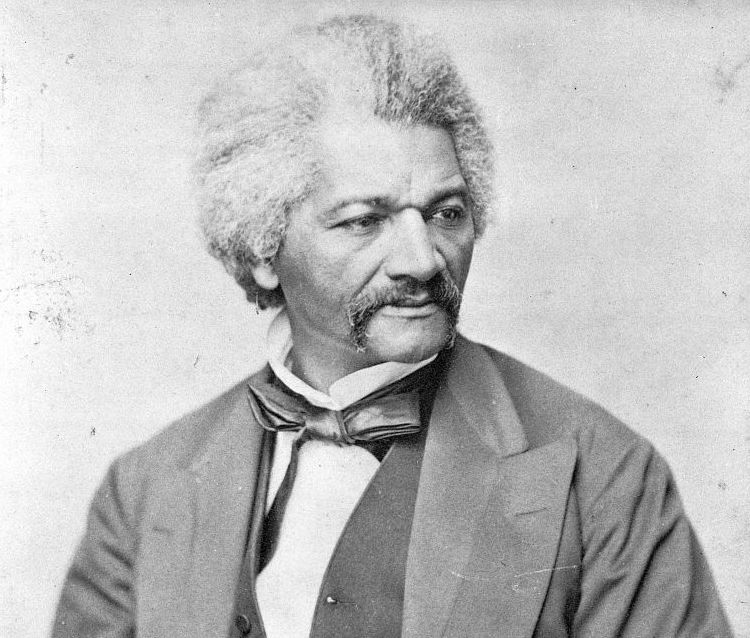

Frederick Douglass in April 1870. Library of Congress

Frederick Douglass was many things: a gifted writer, a brilliant orator, a shrewd political strategist. But he was most certainly not a pacifist. He welcomed the Civil War as the best means to end slavery and helped two of his sons enlist in the Union army.

Douglass was also a longtime confidant and admirer of John Brown, and well after the lethal Harpers Ferry Raid in October 1859, Douglass continued to pay tribute to the man that he (along with other devotees) called Captain Brown.

None of this is in dispute. Yet what’s largely forgotten — and considerably more controversial — is Douglass’s murky role in the Harpers Ferry assault. A key member of Brown’s army allegedly told authorities that Douglass had broken his promise to join the insurrection. And well into the twentieth century, several of Brown’s immediate descendants, along with a friend from Boston who visited him as he faced execution, echoed this claim.

The prevailing historical interpretation is that Douglass rejected Brown’s plan as a suicide mission. That view, however, is based almost entirely on Douglass’s own accounts of the uprising.

In late October 1859, two weeks after the assault on Harpers Ferry sparked a nationwide frenzy (and a manhunt for him), Douglass wrote a widely reprinted letter to the Rochester Democrat denying his involvement. Two decades later, in his third autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, the author fully spelled out his case — and provided the basis for most subsequent accounts of his connection (or lack thereof) to the Harpers Ferry raid.

The pivotal moment came in late August 1859, when Douglass met Brown in a quarry near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania (sixty miles north of Harpers Ferry, then in Virginia). According to Douglass, his radical friend called for “the taking of Harpers Ferry, of which Captain Brown had merely hinted before.” Douglass says he balked at the change of plans, because he viewed the arsenal town as a “steel-trap.” He claims to have instead favored an earlier blueprint that called for establishing a network of small encampments in the Alleghenies and encouraging slaves from the surrounding areas to flee.

But there’s reason to question Douglass’s account.

En route to the weekend summit in Chambersburg, Douglass had spent a night in Brooklyn at the home of two of the city’s leading black abolitionists, Reverend James Gloucester and his wife Elizabeth, a very successful businesswoman. Of Brown’s black correspondents, historian Benjamin Quarles later wrote, “none spoke in more militant tones than James Gloucester.”

After Douglass’s stay, Elizabeth Gloucester gave him a short letter to deliver to Brown. Her note highlighted the famous abolitionist’s excitement about Brown’s work. “The visit of our mutual friend Douglass,” she said, “has somewhat revived my rather drooping spirits in the cause, but seeing such ambition & enterprise in him I am again encouraged.” She enclosed ten dollars in the letter, which Douglass passed along to Brown a few days later.

Whether the Gloucesters would have shown such enthusiasm for the plan Douglass claimed to support is not clear.

In a March 1858 letter, penned after Brown’s recent week-long stay at his home in Downtown Brooklyn, Rev. Gloucester told his houseguest that “in the language of that noble patriot of his country (Patrick Henry) [we shall] now use the means that God and nature ha[ve] placed within our power.” He then pledged twenty-five dollars in support of Brown’s developing plans, which Douglass subsequently delivered.

When Elizabeth died in 1883, James told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle that en route to Harpers Ferry, Brown had remarked to her, “I wish you were a man, for I’d like to have you invade the South with my little band.”

Douglass mentions his stay in Brooklyn in his own account, citing it as a key reason why he wouldn’t have been able to defeat the criminal charges he faced in Virginia. “They could prove I brought money” to Brown, he writes — making made him an accomplice to an act of treason.

In the aftermath of the Harpers Ferry uprising, John E. Cook, Brown’s advance man for the raid, ratted out Douglass, reportedly telling authorities that Douglass did not carry out his end of the mission. According to the Richmond Daily Dispatch, Cook informed his captors that Douglass was supposed to arrive with a “large band” of fellow raiders at a schoolhouse near Harpers Ferry, which Cook had seized on the Monday morning after the Sunday night assault. “I conveyed the arms there for him and waited until nearly night, but the coward did not come,” Cook was quoted as saying.

That detail didn’t make it into Cook’s lengthy confession, read before the court. But Cook did state that Douglass was fully aware of the planned raid. The teacher whose school was seized also told the court that Cook had spoken of Douglass’s involvement in plotting the attack, which was supposed to have grown exponentially larger that Monday. (He didn’t specifically state that Douglass was slated to show up, however.)

As Brown awaited the gallows, two of his longtime white abolitionist allies from Boston, Judge Thomas and Nellie Russell, paid him a visit. A half-century later, Nellie told the New York Evening Post that the condemned figurehead had bemoaned the “great opportunity lost” at Harpers Ferry, and claimed, “That we owe to the famous Mr. Frederick Douglass.” And historian Louis A. DeCaro Jr reports that Brown’s family was similarly sour about Douglass’s actions. Beginning with his children Anne Brown Adams and John Brown Jr, and continuing for several subsequent generations, the martyred abolitionist’s family felt betrayed by Douglass.

For the Northern pro-slavery press in the fall of 1859, there was little doubt about Douglass’s involvement. The New York Herald, the nation’s leading newspaper and a Democratic Party organ, called him a “poor, pitiful coward,” while the kindred Brooklyn Daily Eagle contrasted “the Roman firmness” Brown displayed in court with “the flight of the skulking and cowardly negro, Douglass, who promised to stand by him.” (Brown’s bravery earned him many admirers among the pro-slavery crowd, most notably John Wilkes Booth, who attended his execution.)

But it wasn’t just Democratic voices that commented on Douglass’s ties to the Harpers Ferry action.

The Weekly Anglo-African, a newspaper published by black abolitionists from Brooklyn, also added a distinct perspective. During its short run (1859–1865), the paper’s leading figures included Douglass allies like James Gloucester, James McCune Smith, and the radical white abolitionist journalist James Redpath. Douglass was close enough to the paper’s staff that, during his August 1859 stay-over at the Gloucesters’ home, he paid a visit to the Anglo-African office.

After the failed uprising at Harpers Ferry, the Anglo-African wrote of the incursion: “It seems to have been at the outset, an attempt to procure a large stampede of slaves, and to have grown, by force of circumstances, into an invasion of these United States and of the commonwealth of Virginia.” The paper had nothing but praise for Brown, during his trial noting that his “determination to implicate no others even to save himself, is another proof of the moral grandeur of the man.”

In its November 11, 1859 issue, the paper reprinted Douglass’s lengthy October 31 letter to the Rochester Democrat, in which he stridently rejected Cook’s allegations but did not criticize Brown.

It followed up the statement from Douglass with two (of the 102) letters found in Brown’s carpetbag upon capture. The first was the note from Elizabeth Gloucester that highlighted Douglass’s enthusiasm about “the cause.” The second was from Brown’s friend James H. Harris, who had been trying, unsuccessfully, to recruit support for the attack among black abolitionists in Cleveland.

The editorial decision demonstrated the support Brown commanded in the Anglo-African’s Brooklyn circle. But it also clearly illustrated Douglass’s central role in rallying support for the raid.

Alas, there’s no definitive proof that Douglass did or didn’t intend to participate in the “first battle” of the Civil War. But soon afterward, Douglass told a notable joke to a friendly audience in Edinburgh. As reported in the Scottish press, the nineteenth century’s foremost black abolitionist said of the Harpers Ferry action: “It was not for him to say whether he was justly implicated in the matter or just not there.”