The Neoconservative Counterrevolution

In the anti-sixties backlash, neoconservatives were the most formidable intellectual opponents of social progress.

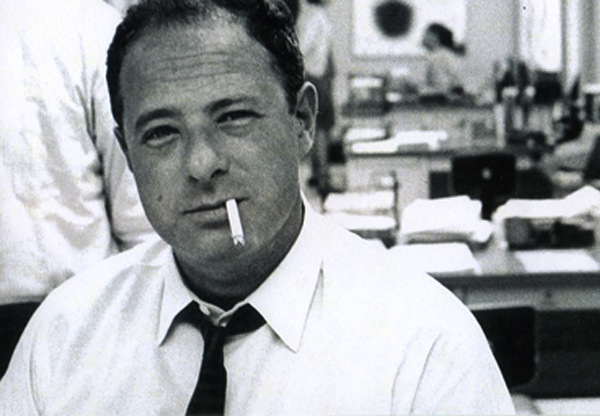

Norman Podhoretz, one of the leading figures of neoconservatism, at the Commentary office in the 1960s. Gert Berliner

If New Leftists gave shape to one side of the culture wars, those who came to be called neoconservatives were hugely influential in shaping the other. Neoconservatism, a label applied to a group of prominent liberal intellectuals who moved right on the American political spectrum during the sixties, took form precisely in opposition to the New Left.

In their reaction to the New Left, in their spirited defense of traditional American institutions, and in their full-throated attack on those intellectuals who composed, in Lionel Trilling’s words, an “adversary culture,” neoconservatives helped draw up the very terms of the culture wars.

When we think about the neoconservative persuasion as the flip side of the New Left, it should be historically situated relative to what Corey Robin labels “the reactionary mind.” Robin considers conservatism “a meditation on — and theoretical rendition of — the felt experience of having power, seeing it threatened, and trying to win it back.”

In somewhat similar fashion, George H. Nash defines conservatism as “resistance to certain forces perceived to be leftist, revolutionary, and profoundly subversive.” Plenty of Americans experienced the various New Left movements of the sixties as “profoundly subversive” of the status quo. Neoconservatives articulated this reaction best. In a national culture transformed by sixties liberation movements, neoconservatives became famous for their efforts to “win it back.”

Neoconservatism was the New Left’s chief ideological opponent. In assuming such a duty, neoconservatives set themselves up for a hostile response. Fortunately for them, their prior experiences had prepared them well for the task.

Many of the early neoconservatives were members of “the family,” Murray Kempton’s apt designation for that disputatious tribe otherwise known as the New York intellectuals. They had come of age in the 1930s at the City College of New York (CCNY), a common destination for smart working-class Jews who otherwise might have attended Ivy League schools, where quotas prohibited much Jewish enrollment until after World War II.

Gertrude Himmelfarb, Irving Kristol, and their milieu learned the art of polemics during years spent in the CCNY cafeteria’s celebrated Alcove No. 1, where young Trotskyists waged ideological warfare against the Communist students who occupied Alcove No. 2. During their flirtations with Trotskyism in the 1930s, when tussles with other radical students seemed like a matter of life and death, future neoconservatives developed habits of mind that never atrophied.

They held on to their combative spirits, their fondness for sweeping declarations, and their suspicion of leftist dogma. Such an epistemological background endowed neoconservatives with what seemed like an intuitive capacity for critiquing New Left arguments. They were uniquely qualified for the job of translating New Left discourses for a conservative movement fervent in its desire to know its enemy.

In 1965 Kristol started a new journal along with his fellow New York intellectual and former Alcove No. 1 comrade, the sociologist Daniel Bell. Originally Kristol and Bell sought to position their journal above the ideological fray. This was made clear by its title, The Public Interest, which derived from a telling Walter Lippmann passage: “The public interest may be presumed to be what men would choose if they saw clearly, thought rationally, acted disinterestedly and benevolently.”

The journal quickly became renowned for its profound skepticism regarding the merits of liberal reform. In fact, The Public Interest was instrumental in undermining the liberal idea that government policy could solve problems related to racism and poverty. It consistently featured influential scholars who considered such notions naive and ultimately dangerous in their proclivity to make things worse.

Kristol, who had showed early signs of pessimism about liberal reform, led the magazine’s charge in this direction. Although throughout most of the sixties he claimed to support a generous welfare system for poor Americans, the title of a Harper’s piece he wrote in 1963 — “Is the Welfare State Obsolete?” — testified to his latent suspicions.

In 1971 Kristol conveyed his misgivings more explicitly in an unfavorable Atlantic review of Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward’s “crude” and “quasi-Marxist” book Regulating the Poor: The Function of Public Welfare. Whereas Piven and Cloward contended that poor people deserved welfare benefits that were more generous and came with fewer strings attached, Kristol believed that welfare had become “a vicious circle in which the best of intentions merge into the worst of results.” Anticipating a slew of later conservative welfare critics, Kristol argued that a more generous welfare system would create more dependency.

Even though Kristol acknowledged in 1963 that he considered some aspects of the Democratic Party’s efforts to expand the welfare state dubious, his allegiance to the party of Cold War liberalism persisted through 1968, when he voted for Democratic presidential nominee Hubert Humphrey. But a mere two years later Kristol was dining at the White House with Nixon, the two men brought together by their shared hatred of the New Left.

According to the New York Times, which reported on the Nixon-Kristol dinner as part of a story on the administration’s intensification of surveillance measures in the wake of New Left bombings, Kristol agreed with Nixon’s crackdown, comparing “young, middle-class, white Americans who are resorting to violence” to the privileged Russian Narodniki who murdered Czar Alexander.

In 1972 Kristol joined forty-five intellectuals, including Himmelfarb and several other incipient neoconservatives, in signing a full-page advertisement that ran in the New York Times just prior to Nixon’s landslide defeat of George McGovern. “Of the two major candidates for the Presidency of the United States,” the signatories declared, “we believe that Richard Nixon has demonstrated superior capacity for prudent and responsible leadership.”

Kristol and his colleagues might have remained Democrats in 1972 had their only major point of contention been with the party’s well-intended if ineffective welfare policies. They pulled the lever for Nixon rather because they believed the New Left, in the form of the “New Politics” movement that enabled the McGovern nomination, had captured the Democratic Party. 1972, in sum, was the year Kristol became a full-fledged member of the conservative movement.

Although the McGovern nomination represented a breaking point for Kristol and many other Cold War liberals, their frustration with the increasing influence of the New Left had been bubbling toward the surface for years. The earliest flashpoint was the controversy that engulfed what became forever known as “the Moynihan Report.”

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, an urban sociologist who regularly contributed to The Public Interest and who went on to a long career in politics that culminated in a twenty-four-year tenure in the US Senate, wrote a polarizing paper in 1965 while serving as assistant secretary of labor in the Johnson administration.

In his controversial report, officially titled The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, Moynihan argued that the equal rights won by blacks in the legal realm — fruits born of the civil rights movement — brought newfound expectations of equal results. But achieving equal results would prove more difficult because blacks lacked the cultural conditioning necessary to compete with whites. For hard-boiled skeptics like Moynihan, the idea that culture impeded liberal reform efforts was an illuminating lens through which to view black poverty.

The Moynihan Report quickly became a national sensation. In part this was due to the violent race riot that exploded in Watts that summer: Moynihan’s theory was the conventional explanation for why blacks revolted so angrily even after passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. The Wall Street Journal spelled out Watts in an article inspired by the Moynihan Report, titled “Family Life Breakdown in Negro Slums Sows Seeds of Race Violence — Husbandless Homes Spawn Young Hoodlums, Impede Reforms, Sociologists Say.”

Beyond this mindless echo, though, reactions to the Moynihan Report were diverse. A self-described “disgusted taxpayer” from Louisiana sent a caustic letter to Moynihan that encapsulated the racist response: “People like you make me sick. You go to school most of your life and have a lot of book learning but you know as much about the Negro as I know about Eskimos. There has never been a Negro family to deteriorate, that is, not a family as white people know a family.”

Moynihan expected such bitterness from Jim Crow apologists. But he was caught him off guard when a host of civil rights leaders and intellectuals denounced the report’s gratuitous emphasis on black pathology, worrying that it would be used as justification for limiting the scope of reform. Writing in the New York Review of Books, Christopher Jencks critiqued Moynihan’s “guiding assumption that social pathology is caused less by basic defects in the social system than by defects in particular individuals and groups which prevent their adjusting to the system. The prescription is therefore to change the deviance, not the system.”

Owing in part to the ideological success of the sixties liberation movements, especially Black Power, a large number of critics sharply rejected the logic that undergirded much of the Moynihan Report. In particular, Moynihan’s left-leaning detractors dismissed the conceit that African-American culture was a distorted version of white American culture. They also repudiated the corollary assumption that assimilation to prescribed norms — to normative America — was the only path to equality.

In his bitter takedown of the Moynihan Report, William Ryan, a psychologist and civil rights activist, coined the phrase “blaming the victim” for what he described as Moynihan’s act of “justifying inequality by finding defects in the victims of inequality.”

Just as Black Power theorists Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton explained racial inequality in institutional terms, Ryan emphasized how the American social structure favored whites over blacks. The behavior of poor blacks, whether actually dysfunctional or not — and Ryan raised concerns about the validity of this claim — was nothing more than a red herring.

Moynihan’s shift from liberalism to neoconservatism, perhaps more than that of anyone else who traveled these grounds, was partially due to the personal anguish he suffered when his left-leaning critics accused him of “blaming the victim,” a polite way of calling him a racist.

“I had spent much of my adult life working for racial equality,” Moynihan later reflected, “had helped put together the antipoverty program, had set the theme and written the first draft of President Johnson’s address at Howard University, which he was to describe as the finest civil rights speech he ever gave, only to find myself suddenly a symbol of reaction.”

In his 1967 article describing the fallout, Moynihan concluded that honest debate about race and poverty was no longer possible. “The time when white men, whatever their motives, could tell Negroes what was or was not good for them, is now definitely and decidedly over. An era of bad manners is certainly begun.”

From Moynihan’s perspective, the failure of the Left to address the causes of urban disorder meant that it had become “necessary,” as he told an audience of stalwart Cold War liberals in 1967, “to seek out and make much more effective alliances with political conservatives.”

Included among the prominent intellectuals whom Moynihan counted as Nixon’s allies was Norman Podhoretz, the longtime editor of Commentary, another magazine crucial to the formation of the neoconservative persuasion. Like Kristol and the other New York intellectuals, Podhoretz grew up in Brooklyn, raised by working-class Jewish immigrants. In contrast, however, Podhoretz had attended Columbia University. Ten years Kristol’s junior, he was among the first generation of working-class Jews admitted to Ivy League schools in the years immediately following World War II.

In the 1970s Podhoretz joined Kristol as a leading light of the conservative intellectual movement. But to reach this final destination the two traveled somewhat different roads. Unlike the Alcove No. 1 generation, Podhoretz was never a Trotskyist. He positioned himself as a Cold War liberal throughout most of the 1950s, but in contrast with the focus of the former Trotskyists, anticommunism was not yet his chief concern at that time.

Like Moynihan’s, Podhoretz’s break with the Left was motivated in part by personal factors. And like Kristol, Podhoretz gave off early signals that such a break was coming. In 1963 he wrote an essay for Commentary, “My Negro Problem — and Ours,” that generated buzz among the literati for its honest admission that most whites, even liberals, were “twisted and sick in their feelings about Negroes.”

In a conversation with James Baldwin, who convinced Podhoretz to write “My Negro Problem,” Podhoretz said he had grown weary of black arguments for special treatment, given that Jews never received such treatment and yet had managed to overcome past discrimination. He pointed to his childhood memories of the black children in his Brooklyn neighborhood: rather than focus on their studies as he and his Jewish friends did, they roamed the streets terrorizing Podhoretz and the other white children.

In writing this piece, Podhoretz claimed his intention was merely to demonstrate the difficulties presented by racial integration. But plenty of readers interpreted it differently. Stokely Carmichael, never one to mince words, proclaimed Podhoretz, simply, a “racist.”

In the aftermath of this and other literary dust-ups, Podhoretz distanced himself from New York intellectual life, where he had become persona non grata. He even took a hiatus from Commentary. During this interlude, he had what he later described in religious terms as a conversion experience. By the time he returned to his editorial desk in 1970, Podhoretz was an unapologetic neoconservative. He earnestly commenced an ideological offensive against the New Left, the counterculture, and all that he deemed subversive about the sixties.

In one of his first post-conversion editorials, Podhoretz argued that the lesson to learn from the sixties was that heady political optimism was more damaging than the pessimism that had pervaded the 1950s. He also rationalized his own political peregrinations by claiming that he and the New York intellectuals arrived at their various positions, including radicalism, “via the route of ideas,” as opposed to most New Leftists, who followed “the route of personal grievance.”

Podhoretz and the neoconservatives assumed that their political cues were abstract, impersonal, and objective. In contrast, New Leftists — student radicals, feminists, and black militants — responded to a set of particular, personal, and subjective signals.

Podhoretz thought that nothing less than the soul of America was at stake in his campaign to stamp out the New Left’s undue influence. By the early 1970s, he had declared ideological war against those who had taken up the cause of the Beats, those New Leftists and counterculture enthusiasts who cast middle-class American values “in terms that are drenched in an arrogant contempt for the lives of millions and millions of people.”

“Are they not expressing,” Podhoretz asked, “the yearning notto be Americans?” He and his fellow neoconservatives were unable to sympathize with people who hated a country that had given them so much opportunity. Where else could Jews from working-class backgrounds achieve so much, they wondered.

In seeking to explain an attitude that seemed to them almost inexplicable, the neoconservatives developed a persuasive theory about a “new class” of powerful people whose collective interests were inimical to traditional America. They innovated this theory by reworking an older Soviet dissident discourse founded by nineteenth-century anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, whom the anti-Stalinist Left deemed a prophet for anticipating that Marx’s “dictatorship of the proletariat” would devolve into “the most distressing, offensive, and despicable type of government in the world.”

“New class” thought gained a larger audience in the United States after the publication of Yugoslav dissenter Milovan Djilas’s 1957 book The New Class, which postulated that the communist elite gained power through the acquisition of knowledge as opposed to the acquisition of property. Used interchangeably with “the new class” was Lionel Trilling’s observation of the popularization of “adversary culture” that had migrated from bohemian enclaves into the masses.

For neoconservatives, these ideas were powerful tools for understanding the anti-American turn taken by those in academia, media, fine arts, foundations, and even some realms of government, such as the social welfare and regulatory agencies.

Where “new class” thought differed from previous strains of conservative anti-intellectualism was in how neoconservatives formulated it specifically to the task of understanding the New Left. Intellectuals of the older right, in contrast, never worked to get inside the mind of the New Left. More commonly they understood the New Left simply as liberalism followed to its logical conclusion.

Unlike traditionalist conservative thinkers who conflated liberalism with the New Left, neoconservatives believed the New Left had infected the liberal intellectual culture they loved. That they detected such a change was one of the central reasons for their political conversion; it was one of the primary reasons neoconservatives proved so useful to the modern American conservative movement.

By siding against contemporary intellectual mores, Bellow and the neoconservatives aligned with the more authentic sensibilities of average Americans. In other words, the neoconservative mind was the intellectualization of the white working-class ethos. As a Commentary writer put it: “Three working men discoursing of public affairs in a bar may perhaps display more clarity, shrewdness, and common sense” than a representative of the “new class” with his “heavy disquisitions.”

In this way neoconservatives helped make sense of the seemingly incongruous fact that some of nation’s most privileged citizens doubled as its most adversarial. These were the people the Catholic intellectual and budding neoconservative Michael Novak labeled the “Know-Everythings”: “affluent professionals, secular in their values and tastes and initiatives, indifferent to or hostile to the family, equipped with postgraduate degrees and economic security and cultural power.”

Beyond its polemical uses, “new class” theorizing was believable because it was grounded in plausible sociology. Take academics as a case study. By the sixties, the university credential system had become the principal gateway to the professional world, a sorting mechanism for white-collar hierarchy. In this sense, class resentment aimed at academics made sense, in a misplaced sort of way, since they indeed held the levers to any given individual’s future economic success.

The number of faculty members in the United States increased from 48,000 in 1920 to over 600,000 in 1972. As this growing legion of academics tended to lean left in their politics, particularly in the humanities and the social sciences, where debates about the promise of America framed the curriculum, Podhoretz’s claim that “millions upon millions of young people began to be exposed to — one might even say indoctrinated in — the adversary culture of the intellectuals” did not seem so exaggerated.

The intellectual who best elaborated neoconservative anxieties about the trajectory of higher education was Nathan Glazer, another product of CCNY’s Alcove No. 1. In 1964 Glazer took a position in the University of California sociology department. Teaching on the Berkeley campus perfectly positioned him to observe the radicalization of the student movement, from the 1964 Free Speech Movement to the antiwar movement of the later sixties.

In 1969 Glazer argued that student protests menaced the freedoms that had historically thrived at universities. “The threat to free speech, free teaching, free research,” Glazer warned, “comes from radical white students, from militant black students, and from their faculty defenders.”

For Glazer and the neoconservatives, the American university stood for all that they valued about American society: beyond being a forum for free inquiry, it was a meritocratic melting pot where smart people, even working-class Jews, could thrive. An attack on the university was an attack on them.

For this reason, student uprisings arguably did more than any other issue to galvanize formerly liberal intellectuals against the New Left. A host of neoconservatives, including Glazer, Kristol, Bell, philosopher Sidney Hook, and sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset, wrote or edited books about “academic anarchy” and the “rebellion in the university.”

In his 1968 Columbia University commencement speech, given minutes after several hundred radical students staged a walkout, Richard Hofstadter preached that “to imagine that the best way to change a social order is to start by assaulting its most accessible centers of thought and study and criticism is not only to show a complete disregard for the intrinsic character of the university but also to develop a curiously self-destructive strategy for social change.”

Political scientist James Q. Wilson took this argument a theoretical step further in a 1972 Commentary piece where he contended that higher education was digging liberalism’s grave by being far too open to the adversary culture that had taken root in its hallowed halls. “Freedom cannot exist outside some system of order, yet no system of order is immune from intellectual assault.”

In issuing an ominous warning that “the bonds of civility upon which the maintenance of society depends are more fragile than we often admit,” Wilson hinted that the United States manifested conditions precariously similar to those of Weimar Germany, a specious comparison that nonetheless became a neoconservative mantra.

In his Commentary article, Wilson listed a number of changes to higher education that he disliked, including the controversial “adoption of quota systems either to reduce the admissions of certain kinds of students or enhance the admissions of other kinds.” Neoconservatives were the first and most vociferous critics of racial quotas, embraced by many universities in the sixties as a way to comply with President Johnson’s Executive Order 11246, which mandated that “equality as a fact” necessitated affirmative action.

In 1968 political scientist John Bunzel authored a critical article for The Public Interest about the newly formed black studies program at San Francisco State College, where he taught. Bunzel worried that black studies would intensify the groupthink tendencies he believed were inherent to Black Power and other identity-based movements and that it would “would substitute propaganda for omission,” “new myths for old lies.”

Quotas were formative to neoconservative thought because they drove a wedge between Jews and blacks, an interethnic alliance that had helped cement the powerful New Deal coalition that had dominated Democratic and national politics since the 1930s.

Of course neoconservatives typically made their case against quotas in nonethnic and nonracial terms. Podhoretz, speaking as an abstract American, contended that quotas fundamentally upended the “basic principle of the American system,” that the individual is the primary “subject and object of all law, policy, and thought.” Podhoretz’s point willfully ignored that Jews merely ten years his senior, including Kristol, had been unable to attend Ivy League universities due to anti-Jewish quotas.

Moynihan, as a Catholic, addressed the issue in a way his Jewish intellectual friends could not. “Let me be blunt,” Moynihan stated. “If ethnic quotas are to be imposed on American universities and similar quasipublic institutions, it is Jews who will be almost driven out. They are not but three percent of the population.”

In other words, since the end of the older quota system that protected WASP privilege, Jews had made remarkable advances, especially in higher education and in the professions that required advanced degrees — advances disproportionate to their overall numbers. As a result, Moynihan and other neoconservatives reasoned that race and ethnic based policies, particularly proportional policies, would only hurt Jews.

Yet far from being ugly racists on the order of Bull Connor, the Birmingham commissioner of public safety whose name became synonymous with the southern white defense of Jim Crow when he unleashed attack dogs and water cannons on nonviolent civil rights activists in 1963, urbane New York intellectuals frowned upon provincial bigotry.

And yet the neoconservative belief that black Americans could overcome racism if only they would work hard — if only, in other words, they would heed the example of Jewish Americans — belied their cosmopolitan pretensions. Neoconservatives were blind to the enormously significant fact that black Americans, as historian David Hollinger writes, “are the only ethno-racial group to inherit a multicentury legacy of group-specific enslavement and extensive, institutionalized debasement under the ordinance of federal constitutional authority.”

Neoconservatives’ obvious misreading of history quite possibly stemmed from the fact that they understood their own peculiar circumstances to be more universal than they in fact were. In this, neoconservatives viewed America through the lens of the typical assimilated immigrant, more learned, for sure, but still typical. As Jacob Heilbrunn argues more broadly about the neoconservative shift from Left to Right, the way to appreciate it “may be to focus on neoconservatism as an uneasy, controversial, and tempestuous drama of Jewish immigrant assimilation — a very American story.”

By moving discourse away from overt racism and toward a “color-blind” defense of individual merit — “Is color the test of competence?” — neoconservatives also pivoted away from Black Power–inflected discussions of institutional racism. In this neoconservative racial thought melded with microeconomic forms of social analysis that were gaining a foothold in academic and policy circles.

Neoconservatives, in other words, turned the cultural radicalism of the New Left on its head by arguing that adversarial ideologies made for both bad culture and bad economics. They interpreted New Left movements as both hostile to traditional American values and dangerously anticapitalist. Neoconservatives tapped into a powerful American political language that separated those who earn their way from those who do not.

As George H. Nash convincingly argues, the conservative turn taken by the Jews at Commentary demonstrated that Jews were more of the mainstream than ever before.

“In 1945, Commentary had been born into a marginal, impoverished, immigrant-based subculture and an intellectual milieu that touted ‘alienation’ and ‘critical nonconformity’ as the true marks of the intellectual vis-à-vis his own culture,” Nash writes. “Two generations later, Commentary stood in the mainstream of American culture, and even of American conservatism, as a celebrant of the fundamental goodness of the American regime, and Norman Podhoretz, an immigrant milkman’s son, was its advocate.”

In celebrating the “fundamental goodness” of America and its institutions, neoconservatives believed they were providing an important service to the regime they loved: they were protecting it from the New Left that they thought was out to destroy it. This shouting match between the New Left and the neoconservatives — this dialectic of the cultural revolution known as the sixties — helped bestow upon America a divide that would become known as the culture wars.

Reprinted with permission from A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars, by Andrew Hartman. Published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2015 The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.